Environment & Nature

Most companies buying renewable energy certificates aren’t actually reducing emissions

The electricity enters an interconnected power grid that distributes it to companies and other users. (Pixabay Photo)

Big companies are increasingly setting voluntary greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets that are derived from the 1.5 C temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. As part of these science-based targets or longer-term net-zero targets, companies commit to rapidly reducing the emissions that come from their electricity consumption.

One approach is to purchase renewable energy certificates, which represent solar, wind and other green energies flowing into the electricity grid.

Our new study shows that companies largely rely on renewable energy certificates to report steep electricity emissions reductions and that this is unlikely to actually reduce emissions.

What are renewable energy certificates?

In most locations, electricity is produced from a mix of renewable and non-renewable energy sources. The electricity enters an interconnected power grid that distributes it to companies and other users.

Since it is not possible to tell apart renewable electricity from non-renewable electricity once it enters the grid, companies cannot technically buy renewable electricity. Instead, companies buy renewable energy certificates, which are issued by power generators every time they add one megawatt-hour of renewable electricity to the grid.

When companies buy these certificates they can claim that they are sourcing or working towards 100 per cent renewable energy. They can also report lower emissions from their electricity consumption. Both things help companies appear green.

The problem with renewable energy certificates

There is a common assumption that more renewable energy is produced when a company buys certificates, and that the emissions from electricity generation decline. This is why accounting standards allow companies to report zero emissions for every megawatt-hour of consumed electricity that is matched by a renewable energy certificate.

Existing research, however, has found very limited evidence supporting the assumed “additionality” of renewable energy certificates. Instead, research suggests that prices of certificates are generally too low and uncertain to influence renewable energy investments.

This is related to the international nature of certificate markets. For example, companies in European countries with dirty energy grids can buy cheap renewable energy certificates issued by old Norwegian hydro-power plants, but this doesn’t lead to more renewable energy generation.

What does this mean for companies’ claimed progress against their emission reduction targets?

Overstated emission reductions

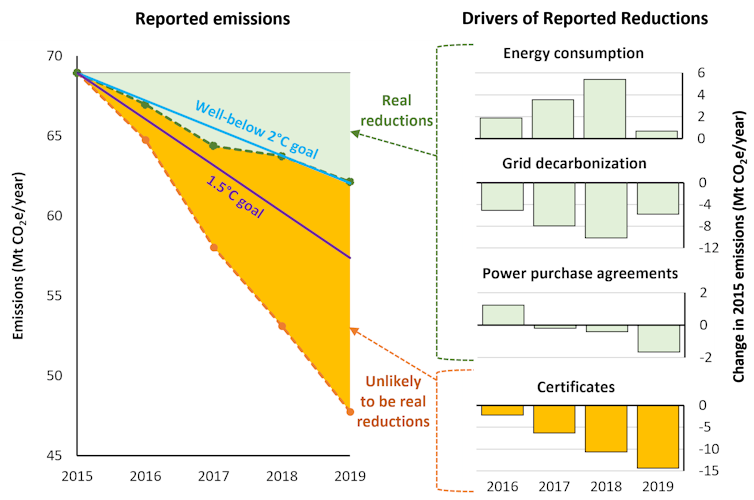

We analyzed the emissions reporting of 115 companies with approved science-based targets. From 2015 to 2019, they reported a 31 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from purchased energy. This made them collectively aligned with the 1.5 C goal of the Paris agreement, according to the 4.2 per cent minimum annual linear reduction rate used by the Science-Based Targets Initiative.

However, 89 per cent of the companies claimed emissions reductions through certificates. In fact, two-thirds of the claimed emissions reductions were from certificates that most likely did not lead to additional renewable energy or emission reductions.

The real combined emissions reduction was closer to 10 per cent, which would barely align with limiting global temperatures to well below 2 C. This overshoot is important because each fraction of a degree increase will lead to more damage and loss to nature and humans.

The 10 per cent reduction was mainly achieved through actual grid decarbonization. But companies increased their electricity consumption in the period, negating some of the emissions reductions that were achieved through decarbonization.

Some certificates do make a difference

Some renewable energy certificates do have the potential to increase the generation of renewable energy. In our study, we singled out certificates based on power purchase agreements because they tend to lead to increased renewable energy.

A power purchase agreement is a contract that obligates the company to buy a certain amount of electricity and the related certificates from a specified renewable energy generator for 10 or more years into the future. This guaranteed long-term revenue stream can be crucial for the energy provider to secure the funding required to expand its generation capacity.

Our study found a small but increasing number of certificates being sourced by companies through power purchase agreements. Some companies are also prioritizing certificates from local renewable energy generators over cheaper certificates from regions with an oversupply, such as Norway.

The way forward

What needs to change for companies’ emissions reporting to be trustworthy? As we see it, at least four things.

- Media should scrutinize corporate claims about renewable energy certificates. As with carbon offsets, media should pressure big companies to provide evidence that their purchase of certificates ultimately leads to emissions reductions.

- Climate-conscious investors should invest in companies that actually contribute to grid-decarbonization.

- Accounting standards should be changed to ensure that companies can claim emissions reductions only when a purchased certificate leads to lower emissions.

- Policymakers looking to mandate corporate emissions accounting should prohibit use of ineffective certificates.

Our study adds to the evidence that companies’ voluntary climate actions can only take us so far. To achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, widespread policy changes that drive emissions reductions are needed across the globe.![]()

Anders Bjørn, Postdoctoral fellow in environmental science, Concordia University; H. Damon Matthews, Professor and Concordia University Research Chair in Climate Science and Sustainability, Concordia University; Matthew Brander, Senior Lecturer in Carbon Accounting, University of Edinburgh, and Shannon M Lloyd, Assistant Professor, Department of Management, John Molson School of Business, Concordia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.