News

Inside new refugee camp like a ‘prison’: Greece and other countries prioritize surveillance over human rights

On the Greek island of Samos you can swim in the same sea where refugees are drowning. The sandy beaches and rolling hills, coloured by an Aegean sunset hide a humanitarian emergency that is symptomatic of a global turn against migration.

During my visit to Samos last week, I was told about refugees being intercepted by Greek authorities without being given the opportunity to claim refugee protection or even speak to a lawyer. Without these opportunities, they are often returned to Turkey under the cover of darkness.

This practice is known as “pushbacks” or “interceptions at sea,” where boats of people seeking refugee protection are returned to Turkish waters by Greek and European authorities without being allowed to claim asylum. This process is facilitated by various surveillance technologies.

I am a lawyer and researcher specializing in how various surveillance technologies impact people on the move. Much of my work takes place on the ground, documenting the use of technology in border spaces like the frontiers of Europe.

The realities for refugees in Greece

I met with a group of refugees from Somalia, who managed to get registered with the authorities due to the quick action of local lawyers, doctors and journalists. But many others aren’t so lucky — I’ve heard stories of Syrian families with babies being sent back to Turkey, and of a woman miscarrying in the forest due to stress.

People aren’t just sent back to Turkey on boats, deaths also happen in the waters of the Aegean Sea.

A group of women from Ivory Coast living in the “jungle” tent-city surrounding the old refugee camp on Samos told me about two young men who drowned during a forced return last week, a case confirmed by the Turkish coast guard.

While the exact details of these stories are difficult to corroborate due to the secrecy of the pushback practices, what is indisputible are people’s experiences butting up against a violent migration regime on the fringes of Europe.

Border violence is a global problem. Scenes of border patrol agents on horseback whipping people from Haiti trying to cross the Rio Grande into Texas are part of the same migration machinery that puts babies on boats in the Aegean Sea and sequesters people for years in Australia’s offshore detention facilities.

For those who survive these journeys, and make it to a place where they can seek protection, they are met with barbed wire, surveillance and segregation.

Refugee camps and surveillance technologies

On Samos, last week marked the opening of a sprawling new refugee camp, tucked away in sun-bleached barren hills over 10 kilometres from Vathy, a major city full of tourists enjoying the beauties of the Aegean island.

I am one of the few people who was able to see inside the new camp during its official opening ceremony on Sept. 18, 2021 during an invited tour.

Once inside, you can see cameras, loudspeakers and various surveillance technologies peppered throughout the camp. It is the first in a series of five proposed refugee camps on the Aegean islands to be full of various surveillance technologies. It has been widely lauded as an “important milestone” in the management of migration by the EU’s Home Affairs.

This new “closed controlled access centre” boasts magnetic gates with kilometres of “double NATO-type security fence” and “smart software” using motion detection algorithms to notify the Local Event Centre and the Control Centre in Athens of any suspicious activity. Various drones and surveillance technologies are also used to monitor the waters of the Aegean Sea, assisting with the maritime interceptions.

This surveillance is entirely funded by the European Union.

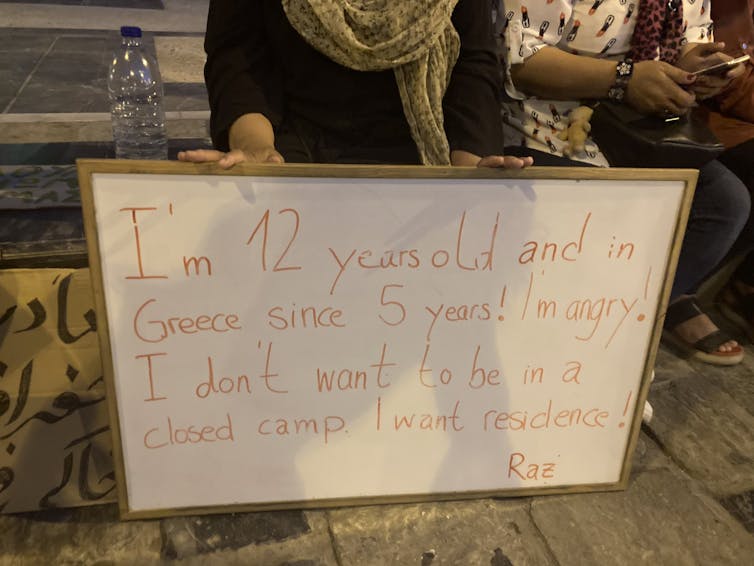

The people I speak with are fearful of what is to come. Some call the new camps a “prison,” and they are worried about being far away from services and always watched. Others worry about further discrimination, or being reduced to fingerprints and eye-scans. While the conditions in many of the current camps are deplorable, securitization and surveillance only serve to further dehumanize people seeking protection

A global appetite for securitization and surveillance

Greece reflects the growing global demand for securitization and surveillance.

Automated decision-making, biometrics and unpiloted drones are increasingly controlling migration as states turn to unregulated technological intervention, fuelled by lucrative and privatized border industrial complex.

Last week, UN Human Rights Chief Michele Bachelet called for a moratorium on high-risk technologies, including border surveillance, but the global migration management industry is not heeding the call.

Greece is just one of the many locations across the world where technological experimentation at the border is given free reign. Our ongoing work at the Refugee Law Lab attempts to weave together the tapestry of the increasingly powerful and global border industrial complex which legitimizes technosolutionism at the expense of human rights and dignity.

These technological experiments don’t occur in a vacuum. Powerful state interests and the private sector increasingly set the stage for what technology is developed and deployed, while communities experiencing the sharp edges of these innovations are consistently left out of the discussion.

Policy makers are increasingly choosing drones over humanitarian policies, with states prioritizing security and surveillance over human rights.

Petra Molnar, Associate Director, Refugee Law Lab, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.