Canada News

Meng and the two Michaels: Why China’s hostage diplomacy failed

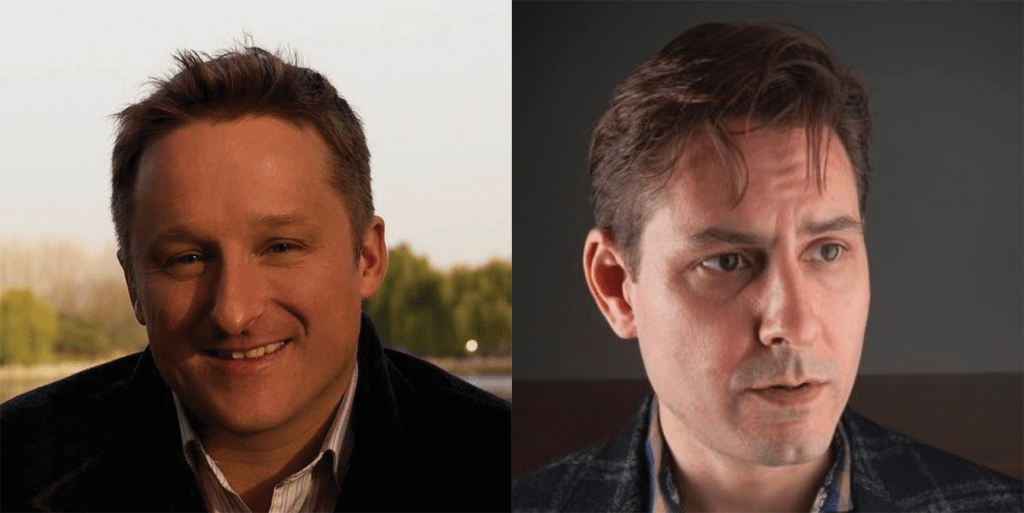

On the face of it, the fact that Canada’s “two Michaels” — Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor — boarded a Canadian government aircraft in Beijing at about the same time that Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou was being released from her extradition hearing bail requirements in Vancouver might indicate to some that China’s “hostage diplomacy” was successful.

Read more: Meng for the two Michaels: Lessons for the world from the China-Canada prisoner swap

There was a clear link between Meng’s plea bargain arrangement with the United States Department of Justice, her subsequent release in Vancouver and the release of the two Michaels after more than 1,000 days in captivity.

Despite consistent Chinese denials over many months that their arrest was in retaliation for the detention of Meng under the Canada-U.S. extradition treaty, the fact that the two cases were resolved simultaneously (even before Kovrig had been sentenced by the Chinese court) stripped away any pretence that there was no connection.

In the past, in cases involving detention in China of foreign nationals when there have been unrelated disputes with their country of origin, the release of the “hostages” has not come for several weeks or months after the resolution of the original dispute.

That’s allowed China to maintain the fiction that it doesn’t detain people for retaliatory purposes and to argue that Chinese law must run its course. This time, even that fig leaf was removed.

Deferred prosecution agreement

In order to secure her release, Meng was given only the lightest of punishments, a deferred prosecution arrangement that required her to neither plead guilty nor pay a fine.

Read more: SNC-Lavalin: Deferred prosecution deals aren’t get-out-of-jail free cards

All she was required to do was consent to a statement of facts that outlined the U.S. view of what happened when she allegedly misled global bank HSBC into believing that a Huawei subsidiary operating in Iran was not in fact controlled by Huawei.

The deferred prosecution agreement will expire in 2022, and then the case will be closed.

Do the terms of this settlement demonstrate that the U.S. caved to Chinese hostage diplomacy by cutting such a generous deal?

The need to free Kovrig and Spavor was no doubt a factor given the pressure the Canadian government was putting on U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration to withdraw the extradition request. But it was far from the only consideration.

The Department of Justice has emerged from the case with their minimum requirements met, namely an acknowledgement of their ability to enforce American sanctions on foreign companies if financial transactions go through the U.S. That’s not a bad outcome considering the flimsiness of the American legal case against Meng in the first place.

The threadbare nature of the evidence against Meng was increasingly exposed in the British Columbia Supreme Court extradition hearings as Meng’s legal team challenged the case presented by Canadian Crown attorneys on behalf of the U.S. Justice Department.

No smoking gun

Apart from the selective use of evidence by U.S. authorities and the fact that no harm was suffered by HSBC despite being allegedly “misled” by Meng, there was no smoking gun.

There was also the possibility that the B.C. court would find abuse of process given the clumsy way both the RCMP and the Canada Border Services Agency handled Meng’s arrest, and dismiss the case on these grounds.

In other words, the American case against Meng was hardly watertight. They had even offered Meng a plea bargain in December 2020 that would have required her to plead guilty. Huawei rejected that offer.

Rescuing their case with the plea bargain they finally struck was a way for the American authorities to head off the growing possibility of a total loss.

Even though the Meng/two Michaels case has poisoned Canada-China relations, it was actually a U.S.-China dispute. Resolving it — not primarily to free the two Michaels but to remove a U.S.-China irritant — was a low-cost “give” by the Biden administration to get the issue out of the way so it can establish a better dialogue with Beijing.

So what did China achieve with its high-profile hostage diplomacy exercise? It not only fuelled harsh criticism from much of the developed world (which may not bother it too much), but it provided the motivation for Canada to take the lead in producing the Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in State to State Relations, now endorsed by dozens of countries.

Trudeau didn’t give in to pressure

China has no one but itself to blame for being put in the spotlight on this issue. It also failed to succeed in short-circuiting the Canadian and U.S. legal process.

That would have happened if Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government had succumbed to pressure early on to end extradition proceedings against Meng and release her, as a number of retired Canadian politicians and diplomats had proposed.

The Chinese may have miscalculated in believing that by seizing the Michaels, Canada would cave almost immediately and terminate the extradition process.

The fact that the Canadian government insisted that the legal process, slow as it was, had to play out — thus keeping Meng under restricted bail conditions in Canada for almost three years — was surely not something the Chinese leadership had bargained on. It should be a lesson to China in the future, even though Kovrig and Spavor unfortunately had to pay the price of the Chinese miscalculation.

What’s next for Canada-China relationship?

Now that the Meng/two Michaels affair has been resolved, attention will turn to the future of Canada-China relations.

The immediate logjam has been removed, but it will take a long time for the waters to flow smoothly. By resorting to taking hostages rather than working through diplomatic channels, China has destroyed decades of slowly nurtured goodwill and lost the trust of the Canadian public, as well as public opinion in many other parts of the world.

China can pretend to shrug off those concerns, and swagger on the world stage, but despite its impressive economic growth and growing military prowess, it cannot afford to antagonize all the people all the time. Hostage diplomacy is ultimately a losing proposition, a lesson that China has hopefully learned.

Hugh Stephens, Executive Fellow, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary; Distinguished Fellow, Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.