Health

Requests for caesarean birth brushed aside, despite guidelines to respect maternal choices

When first-time mother Melanie approached her obstetrician-gynecologist in Ontario to request a caesarean birth plan, she found his response unsettling.

“I was told I didn’t have a right to choose how I could bring my daughter into this world, that no OB-GYN would honour my request. I would have to get over it and give birth vaginally. He also told me he did not agree with doctors that do honour them.”

Feeling anxious and stressed, Melanie turned to a social media group for help.

Meanwhile, 50 kilometres away in the same province, Jessica made the same request to her doctor. She explains that the idea of someone else deciding what would happen to her body was upsetting.

“Thankfully, I totally lucked out and got an extremely supportive OB-GYN,” said Jessica. “I calmly explained my reasons for wanting a caesarean, and she heard me and agreed right away.”

Variability in maternity care

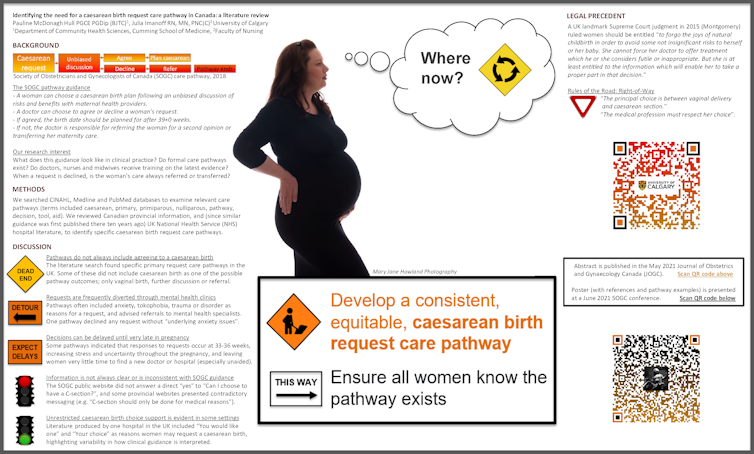

In 2018, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) published guidance on maternal requests for caesarean birth. It advises doctors to explore the reasons for the request and discuss potential risks and benefits. Doctors who disagree with a caesarean birth request have a responsibility to refer the woman for a second opinion or transfer her care. Yet in reality, many women are simply told no.

This prompted a graduate student in my health sciences team, together with a faculty of nursing graduate student, to explore why maternity care experiences can be so different. The initial findings highlight the need for clear, consistent procedures for doctors to follow when presented with caesarean birth requests.

A review of research studies and patient information showed that patient autonomy is supported in principle. However, in clinical practice, requesting a caesarean birth in Canada is similar to the postcode lottery found in the United Kingdom, where hospitals differ in how they interpret and implement caesarean birth guidance.

Information on patient websites such as HealthLink BC and MyHealth Alberta, stating “experts feel that C-section should only be done for medical reasons,” contradicts the SOGC, and also contradicts the evidence.

Research on caesarean birth safety

A recent study from researchers at the University of Ottawa suggests planned caesarean births are safe and may have fewer short-term complications compared to planned vaginal births, which include forceps deliveries and emergency surgery. The team reviewed more than 400,000 low-risk pregnancies in Ontario (2012–2018) where “maternal request” was included in hospital data; a total 0.4 per cent of all births and 3.9 per cent of all caesareans.

They also learned about the women who had requested a caesarean birth — or at least, the women whose requests were agreed to. These women were more likely to be white, older (35+), first-time mothers and more likely to have had anxiety, to gain excess weight during pregnancy, to have more education and to have conceived by IVF.

Doctors often choose caesarean birth

Many doctors choose a caesarean birth for their own children too. A survey of 162 Canadian health-care professionals in 2005 found they were more likely to choose a caesarean for themselves or their partners than they were to offer it to their patients, and this was true for both first-time (at least six per cent) and subsequent births. Yet health professionals can still be refused.

Lydia, a nurse in British Columbia, said: “My request was brushed aside. I broke down in tears saying I didn’t want prolapse, tears or nerve damage, but my doctor said a caesarean wouldn’t be a good choice for me or my baby.”

Lydia “didn’t want to be a pushy patient,” but says that during the birth, “all of my feared concerns, in addition to my son having shoulder dystocia, a compressed cord and being flat at birth” (difficulty breathing, with loss of muscle tone) became a reality. With her second baby, Lydia’s caesarean request was agreed to before she even conceived, and she had what she calls “an amazing experience.”

So why couldn’t this happen the first time too?

Barriers to choice

In line with the World Health Organization’s position — which cites a lack of evidence of benefits for caesareans that aren’t medically necessary, as well as the risks associated with surgery — many doctors disagree with caesarean birth choice. They want to reduce medical interventions, and especially caesarean surgeries.

Even the media statement accompanying the new University of Ottawa research emphasized “reassurance to those concerned about… rising caesarean delivery rates,” with Physician’s Weekly reporting: “Rate of planned C-section on maternal request stable in Canada.”

But at what cost?

Dr. Fiona Mattatall, an obstetrician in Calgary, told us that “denying a patient’s choice in mode of delivery for their pregnancy is an antiquated paternalistic approach to care.” And the inconsistencies described by some Canadian women raise serious inequity concerns.

Knowledge, persistence and luck

Julie describes how her family doctor in Ontario “laughed at my concerns, and said she doubted I’d find someone, but I was too determined to let her throw me off.”

Similarly, Heather in British Columbia says she questioned her first doctor’s advice after checking the medical research database PubMed, and asked for a new doctor, who agreed to her caesarean request. Mary’s doctor in Québec agreed immediately, but Mary was so worried beforehand, “I was even considering abortion should my request for a C-section be denied.”

Women also experience delays. When staff at Lisa’s local hospital in British Columbia told her “they don’t refer patients for elective caesarean,” she had months of “being questioned about it, lectured or brushed off” before being sent to a mental health professional who said, “I don’t even know why you’re here.”

Lisa was 33 weeks pregnant before finally being referred to a doctor who agreed to her request, and was only then able to relax in her pregnancy. She says:

“The only thing that helped was my own persistence and not letting myself be talked out of a choice I was sure I had the right to make.”

Inequities must not continue

Eventually, Melanie in Ontario was also able to find a doctor who agreed to her request, albeit in a different city, and a 40-minute drive each way for all her appointments. “I will definitely be opting for another elective caesarean, and will let no one tell me how to bring my baby into this world, as it’s no one else’s body, and no one else’s experience,” she said.

Importantly, the SOGC’s caesarean guidance followed a British landmark Supreme Court judgment in 2015 that ruled while a woman “cannot force her doctor to offer treatment which he or she considers futile or inappropriate,” the “medical profession must respect her choice.”

Our research concludes that Canada’s maternity care system needs to meet this challenge in ways that afford all women the right to informed choice, without health equity barriers. As Jessica says:

“Quality medical care that is respectful and affirming, that allows you choice and control over your own body, should never be a matter of luck.”

Pauline McDonagh Hull, Graduate student, Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary and Bonnie Lashewicz, Associate Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.