Health

What’s in a name? Why giving monkeypox a new one is a good idea

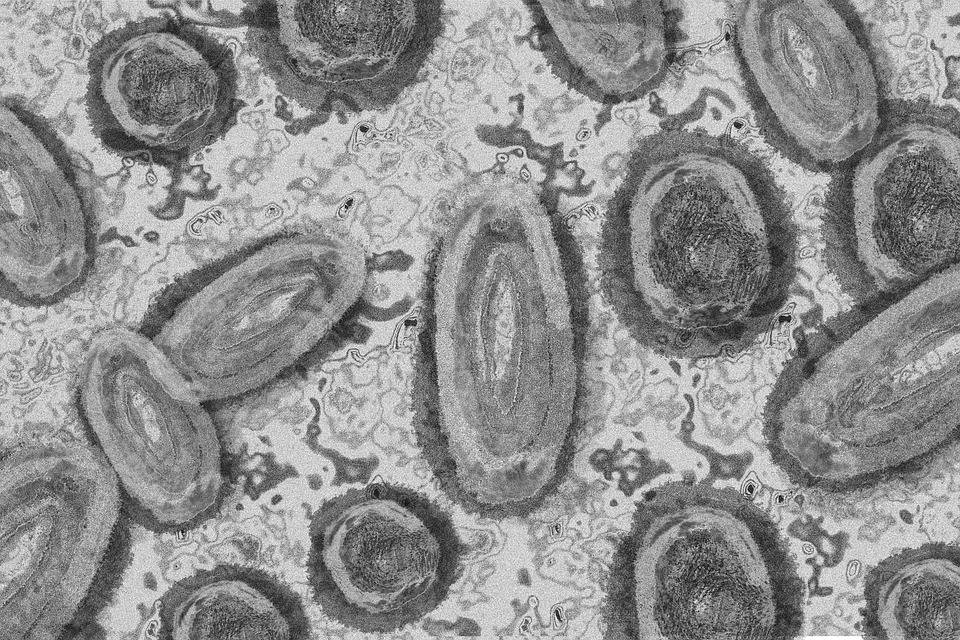

WHO guidelines recommend avoiding animal names or geographic regions for viruses and diseases. (Pixabay photo)

In its latest update on monkey pox in mid-June, the World Health Organization (WHO) said that cases had been reported from 42 member states across five of its regions – the Americas, Africa, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Pacific. A total of 2,103 laboratory cases had been reported, including one death.

The outbreak mostly affected men who had sex with men or who had reported recent sex with new or multiple partners. The WHO pointed out that the unexpected appearance of monkeypox in several regions that hadn’t previously reported cases suggested that there may have been undetected transmission for some time. It said it considered the risk at the global level as moderate.

The debate that dominated the headlines, however, has been around the WHO announcing that it’s “working with partners and experts from around the world on changing the name of monkeypox virus, its clades and the disease it causes”.

Just prior to the WHO’s statement a group of 29 scientists advocated for a non-discriminatory and non-stigmatising nomenclature for monkeypox virus.

They called for a nomenclature or name that is neutral and more acceptable to the global health community. They suggested a naming system similar to the Pango nomenclature used by researchers and public health expert globally to track the transmission and spread of SARS-CoV-2, including variants of concern.

As an African scientist I agree with this call. The new name for monkeypox must be aligned with best practices in naming of infectious diseases to avoid the uninformed negative narrative that associate diseases with regions. There are no wild non-human primates in Europe. There are many monkeys and apes in Africa, Asia, and in Central and South America. Monkeys are usually associated with the global south especially Africa.

In addition, there is a long dark history of black people being compared to monkeys. No disease nomenclature should provide a trigger for this.

The history

Monkeypox is a disease caused by the monkeypox virus, a member of the same family of viruses (Poxviridae) as smallpox. The virus was first identified in laboratory monkeys in the 1950s – hence the name. However, rodents, squirrels and non-human primates are believed to be the reservoir hosts.

The first human monkeypox case was confirmed in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Since then, there have been periodic outbreaks in western and central Africa, where it is endemic in 11 countries. We don’t know the real prevalence of the disease.

Nearly all monkeypox outbreaks in Africa prior to 2022 emanated from spillover from animals to humans. Only rarely have there been reports of sustained human-to-human transmission. This has not been the so with the cases reported since May 2022. The cases presented at healthcare facilities involved people who had travelled to countries outside of Africa.

The main symptom of monkeypox is a rash that looks like chickenpox. Monkeypox can spread through close contact with an infected person’s body fluids, respiratory droplets and contaminated materials.

Monkeypox is rarely a public health emergency. The infections are usually mild, compared to smallpox or chickenpox.

Naming conventions

WHO guidelines recommend avoiding animal names or geographic regions for viruses and diseases.

The current classification of monkeypox virus’ genetic diversity recognises two clades of the virus referred to as the “West African” clade and the “Central African” or “Congo Basin” clade.

Some genome sequences on the NCBI Genbank database use “West African” for the field “strain” or “genotype”.

Lessons learnt from objections to calling the B.1.1.529 variant (omicron) of SARS-CoV-2 as the ‘South African variant’ informed the use of the Pango nomenclature for SARS-CoV-2.

To name infectious diseases based on locations of first detection is misleading because of limited diagnostic or priorities in different regions. It could also delay reporting of new variants of infections discovered in Africa.

As leadership in infectious diseases research in Africa is gaining recognition, African scientists are also working to ensure the gains are not overshadowed by historical prejudices. It is good to know that people are listening.![]()

Moses John Bockarie, Adjunct professor, Njala University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.