News

Elections in Brazil: Lula faces many challenges running against Jair Bolsonaro

(LulaOfficial)

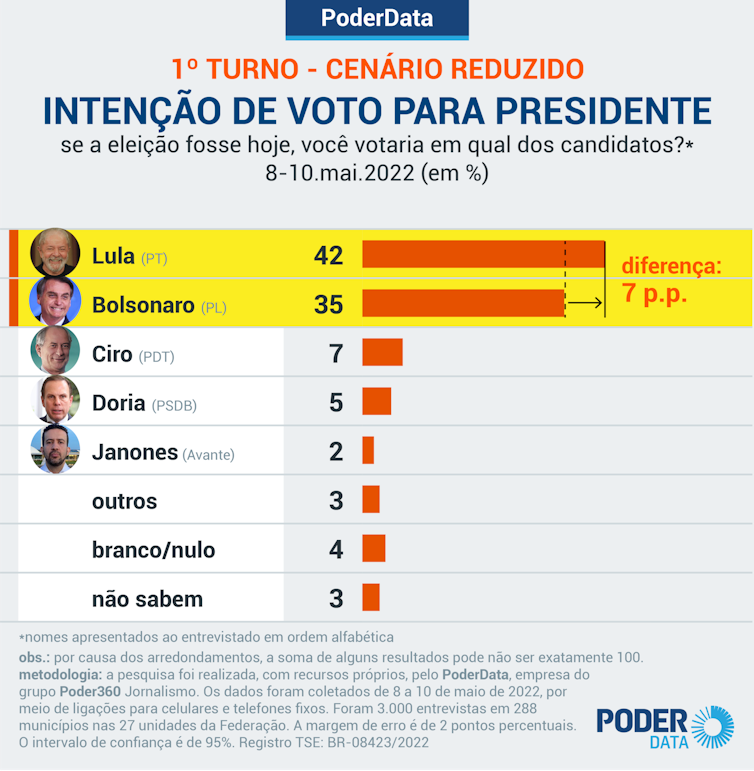

The Brazilian presidential elections will be held on Oct. 2. With four months to go, the former president and figurehead of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT), Lula da Silva, who made his candidacy official with great fanfare on May 7, is considered the favourite to defeat the incumbent, President Jair Bolsonaro, according to polls.

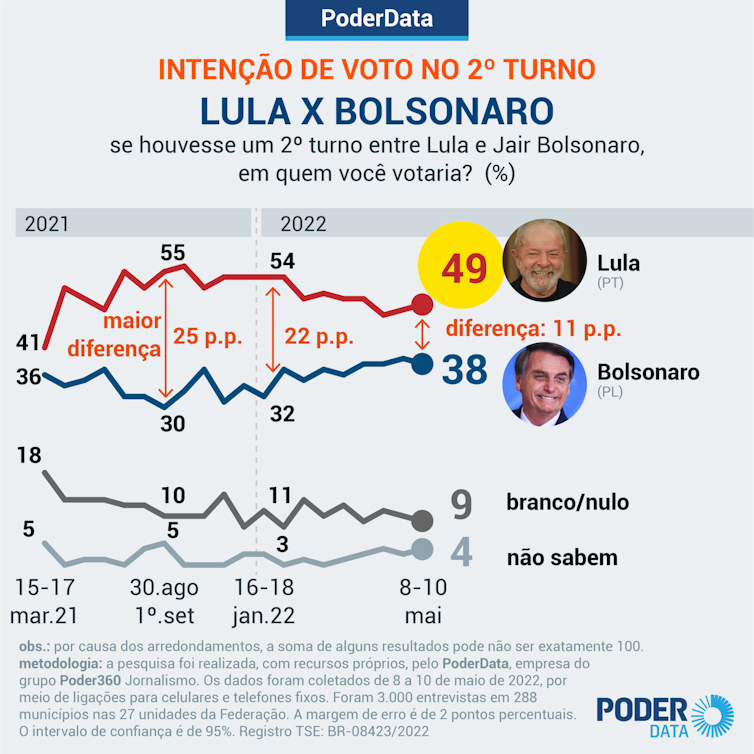

Should the vote go to a second-round runoff, polling shows 11 points would separate the two rivals. Lula, who was president from 2002 to 2010, still enjoys a high level of popularity, particularly in Brazil’s northeast. When he was running for re-election in 2018, the former metalworker built his campaign on the positive results of his previous terms in office using the slogan, “Make Brazil Happy Again.”

In the four years since Bolsonaro was elected, his government has had a dramatic effect on Brazilian society. His catastrophic handling of the COVID-19 pandemic made Brazil the world’s second-most bereaved country, with more than half a million deaths. Deforestation and illegal resource extraction in Indigenous territories reached record levels during his term. Bolsonaro’s hostility towards the judiciary and his clientelism, militarism and nepotism have permanently weakened Brazil’s already fragmented democracy.

As a doctoral student in political science specializing in the study of social movements in Brazil, I worked with Workers’ Party activists during the 2018 elections, among others. In this article, I revisit the main challenges Lula and the Workers’ Party face in the run-up to an election that will be decisive for a country that has become an international pariah since Bolsonaro came to power.

Impeachment, imprisonment and corruption scandals

In 2016, in what she would later call a parliamentary coup, President Dilma Rousseff was impeached for manipulating the federal budget deficit to help with her re-election. The Workers’ Party was subsequently pushed out of the executive branch in spite of its victory in the presidential elections two years earlier.

Many experts, both inside and outside Brazil have condemned the procedure as an undemocratic political changeover indicative of a worrying erosion of democracy.

Two years later, Lula ran for a third term in the 2018 presidential elections. but he was imprisoned for corruption only a few months before the election. And due to a dubious judicial process, notable for its speed, timing and lack of tangible evidence, Lula had to sit by and watch as his protégé, Fernando Haddad, qualified for a second round against Bolsonaro.

The judge who sentenced Lula to eight years in prison, Sergio Moro, confirmed his intentions to become a presidential candidate, but then suspended his campaign to join the conservative União Brasil party. Since Lula’s release in November 2019, after 580 days of imprisonment, he is faced with a Workers’ Party leadership that is now firmly associated with corruption and bad governance in the eyes of part of Brazilian society.

Loss of the Workers’ Party local base

The Workers’ Party is now deeply dependent on its national leaders, including Lula, who, at 76, is running in his seventh presidential campaign. Although the Workers’ Party still performs well at the national level (with five runoff qualifications, including four victories in presidential elections since 2002) and remains the main force of opposition to the government, the party has seen its local base erode since 2016.

In the October 2016 elections, the Workers’ Party won 254 municipalities, down from 644 in 2012. In 2020, the party won only 183 municipalities and no state capitals, a first since the end of military rule in 1985.

Faced with the loss of its local presence, the Workers’ Party, which is increasingly centralized around its leaders, no longer seems to be rebuilding itself from the bottom up or renewing its administration and supporter base.

Lula’s conciliatory strategy

Lula hopes to defeat the ex-military officer and far-right President Bolsonaro by building a broad democratic front around him. To that end, the Workers’ Party has renewed dialogue with some members of the Brazilian Democratic Movement, its centre-right ally until 2016 when it suddenly switched alliances.

Lula chose a historical rival, Geraldo Alckmin, as his running mate. Lula had faced Alckmin twice (in 2002 and 2018), when the latter was a member of the right-wing Brazilian Social Democracy Party. This strategy of conciliation with right-wing elites is a sign that the Workers’ Party agenda is becoming more liberal and confirms the party’s repositioning towards the centre of the political spectrum.

The Workers’ Party has also established an alliance with the far-left Socialism and Liberty Party, whose president, Guilherme Boulos, reached the second round of the 2020 municipal elections in São Paulo. On the other hand, no alliance seems possible at this stage with Ciro Gomes, a centre-left candidate who came third in 2018 with 12 per cent of the vote.

Towards a Lula-Bolsonaro polarization

On the opposing side, President Bolsonaro saw his approval rating drop to 19 per cent at the end of November 2021, notably because of his catastrophic management of the COVID-19 health crisis.

Since January 2022, as the pandemic has stabilized, the public’s voting intentions have risen slowly in Bolsonaro’s favour. Despite several setbacks, in particular the rise in fuel prices, the margin between the Bolsonaro and Lula is narrowing. With this in mind, Bolsonaro is rallying support among evangelicals to attract the religious vote.

Since August 2012, Bolsonaro has repeatedly attacked the electronic voting system, even though it has been used in Brazil for 25 years, raising fears he will refuse to accept the result of the elections if he is defeated.

So, despite a seemingly comfortable lead in the polls, five months before the deadline, Lula da Silva’s victory is far from guaranteed. To retain his lead, he will have to consolidate a heterogeneous alliance and constitute a truly democratic front around him, one that will be able to respond to a candidate who publicly criticizes the electoral and democratic processes, themselves. The reconstruction of the Workers’ Party and the renewal of its administration will have to wait.![]()

Jonas Lefebvre, Doctorant en science politique, Université de Montréal

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.