Health

Longer-acting eye treatment could reduce vision loss for Indigenous Australians

Indigenous people in Australia experience three times more vision loss than non-Indigenous people, creating a concerning gap for vision.

Much of this is due to diabetic macular oedema (DMO). Here, blood vessels in the back of the eye (the retina) are damaged by high blood sugar levels. Over time, this causes swelling (oedema) of the central part of the retina (the macula).

Macular oedema blurs the central vision, diminishing the ability to recognise people’s faces, to drive and work, and perform other essential tasks. DMO affects around 23,000 Indigenous people in Australia, with most of them of working age. Similar trends are reported in other developed states with Indigenous populations, including New Zealand, Canada and the United States.

The good news is DMO is treatable, with medications known as anti-VEGF agents. We undertook a world-first clinical trial to test longer-acting DMO treatment for Indigenous Australians. In doing so, we also learned about undertaking culturally sensitive research on Country.

A longer-lasting treatment

When injected into the eye by an ophthalmologist (an eye surgeon), anti-VEGF drugs are safe and effective for treating DMO. The injections don’t hurt, since the eye is anaesthetised. The catch is that anti-VEGF agents are relatively short-acting, requiring them to be re-administered as often as every month.

Many Indigenous patients find it impractical, for complex and varied reasons, to attend ten to 12 eye appointments a year. There is, therefore, a need for an alternative.

Longer-acting medications do exist. One example is a dexamethasone implant (commercially known as Ozurdex(R)), a steroid injected into the eye. The dexamethasone implant only needs to be dosed every three months.

The dexamethasone implant is PBS approved for DMO in Australia but has never been evaluated in an Indigenous population. This is important because a possible side effect of steroid medications is increased pressure in the eye. If left untreated, this can lead to a condition called steroid-induced glaucoma.

Glaucoma is thought to occur less commonly overall among Indigenous people, suggesting differences in the physiology of eye pressure between Caucasian and Indigenous eyes. Additionally, the incidence of steroid-induced subtype glaucoma has never been studied among Indigenous people. This is particularly important for people in remote locations, since glaucoma is a “silent disease”, requiring regular check ups for detection and treatment.

The historical barriers preventing this sort of research include cultural and geographical factors, as well as a lack of endorsement from Indigenous health services and “staff champions”.

Not just what to research, but how

At the Lions Eye Institute, we sought to overcome these barriers with the OASIS Study – a world-first clinical trial in ophthalmology to exclusively recruit Indigenous patients.

We framed our study around ten key factors for success including support from all participating Aboriginal Medical Services, free and safe treatment, free transport, appointment reminders, and cultural safety training for all trial staff. Wherever possible, study visits were performed within patients’ usual Aboriginal Medical Service. Study participants could have friends, family and staff members present. This helped communication and a sense of safety and trust.

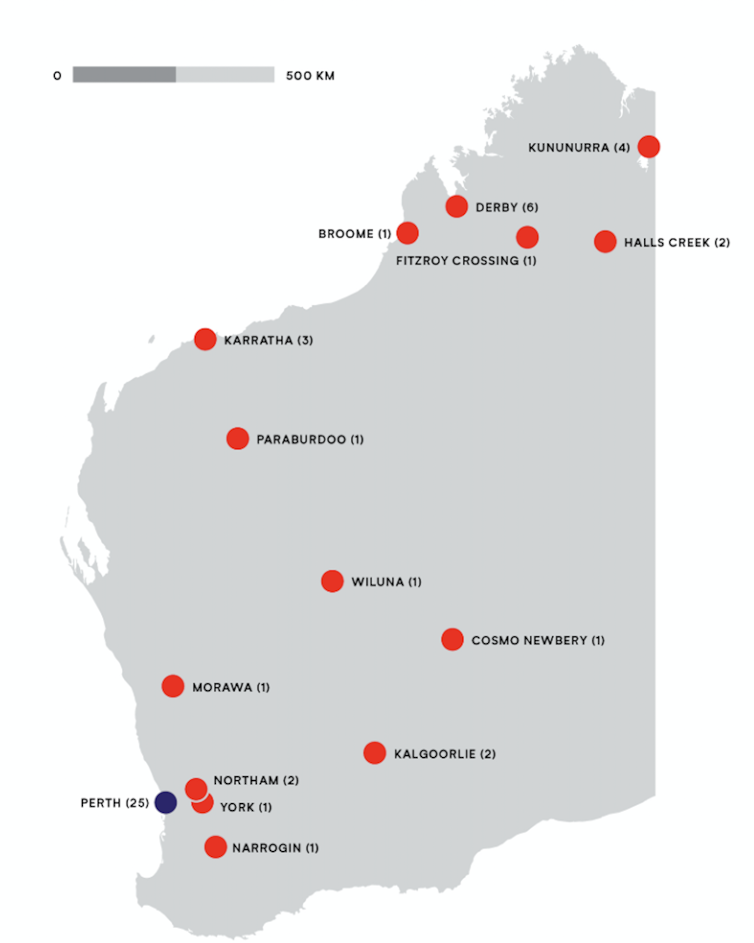

Over two years, we recruited 38 Indigenous patients and 52 eyes (some patients had DMO in both eyes). Patients were recruited from both Perth and country Western Australia. On enrolment, they were randomly assigned to receive dexamethasone implant or an anti-VEGF agent called Avastin. Follow up was performed for check ups and re-treatments. After 12 months, we analysed all our data, to compare the safety and effectiveness of the two drugs.

The results showed patients who received dexamethasone implant gained four extra letters on a standard eye chart, equivalent to a 6.2% improvement in their vision. Those who received the anti-VEGF agent, meanwhile, lost 5.5 letters on average, representing an 8.9% decline.

Taken together, these results represented a 15% (9.5 letter) visual advantage for patients who received dexamethasone implant. In real world terms, this meant patients met the visual requirements for a private driver’s license. Those who received the anti-VEGF agent did not.

This disparity was most pronounced in country towns, where dexamethasone implant had a 37% (24 letter) advantage over the anti-VEGF agent.

Why it works

As we suspected, the reason for the dexamethasone implant’s better performance related to its less frequent, hence more pragmatic, dosing regime.

Over 12 months, patients who were meant to receive four dexamethasone implant injections, received an average of 3.3 injections. This meant that, on average, they received 82.5% of their intended treatments.

Anti-VEGF patients, meanwhile, received 7.2 of their scheduled 12 injections. This equated to only 60% of their intended treatments, and reflects the difficulty of attending monthly appointments in the real world. Anti-VEGF patients had more than twice as many injections as dexamethasone implant patients, yet ended up with poorer vision.

Not all the results were positive. One third of patients who received dexamethasone implant developed high pressure in the eye – a recognised side effect of steroid injections. While not painful, this requires treatment with pressure-lowering drops and close follow up, to prevent glaucoma.

Secondly, steroid injections speed up cataract formation (a clouding of the lens in the eye). This requires access to cataract surgery, which is not always simple to arrange in remote locations. Based on these caveats, we developed guidelines for the judicious use of dexamethasone implant among Indigenous patients, published in March.

Reducing the burden, closing the vision gap

While dexamethasone implants are not perfect, we believe the OASIS Study provides hope for reducing vision loss and the “burden of treatment” for Indigenous Australians with diabetes.

The ability to perform culturally safe clinical trials means new treatments may be similarly evaluated in the future, with consideration given to input from patients through community-controlled research.

Hessom Razavi, Associate professor, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.