News

Why there’s no real ‘common prosperity’ campaign in China

After a meeting led by President Xi Jinping in August 2021, China’s Communist Party released a media summary that spoke, in part, to the idea of “common prosperity.”

Little is new in the communiqué itself, which reiterated the message that ensuring the broad sharing of China’s wealth among the Chinese people is critical to the party’s lasting rule.

It acknowledged that sharing prosperity is a “long-term, difficult and complex” task and only gradual progress can be expected. And it alluded to some public spending policies benefiting the poor and middle class, but merely urged sub-national governments to “experiment” with such policies while committing to no new national measures.

Yet “common prosperity” has grabbed news headlines in the West in recent months. Commentators claim that China is “cracking down on the rich,” “clamping down on capital” and shifting political priorities from economic growth to redistribution.

The business media has gone into overdrive trying to decipher what Xi’s supposed populism means for investors in Chinese stocks. The spectacle of tamed tech giants like Alibaba and Tencent pledging to donate tens of billions to government “common prosperity” funds seems to offer proof of Xi’s ideological turn.

Tax revenues reveal the truth

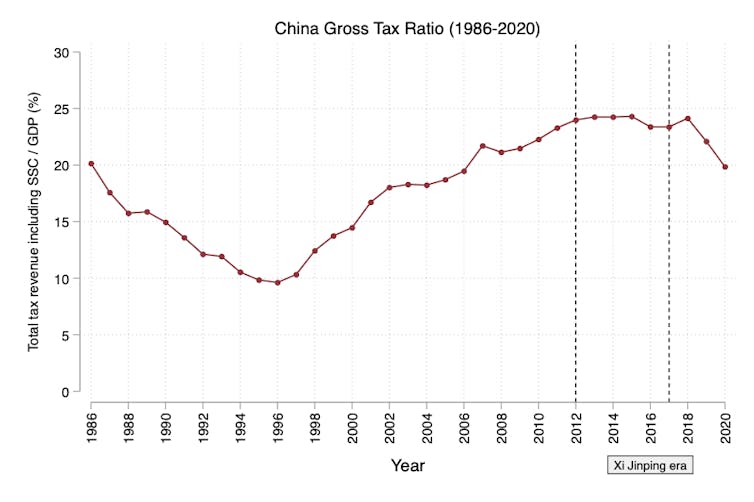

Yet these prognoses are belied by China’s fiscal realities. Consider the evolution of the ratio of tax revenue to gross domestic product (GDP) in China.

This statistic is important because, to pursue redistributive policies whether poverty alleviation, creating a social safety net or supporting economic mobility — a government must raise tax revenue.

What is Xi Jinping’s record in tax collection?

China’s tax-to-GDP ratio enjoyed a sustained rise from 1996 to 2012, but has stagnated since then — precisely during the Xi Jinping era.

If tax revenue had continued to climb as it before 2012, China would have a lot more resources for redistribution than now. Instead, Xi’s rule has so far yielded the most sustained and largest tax cuts in China since 1994.

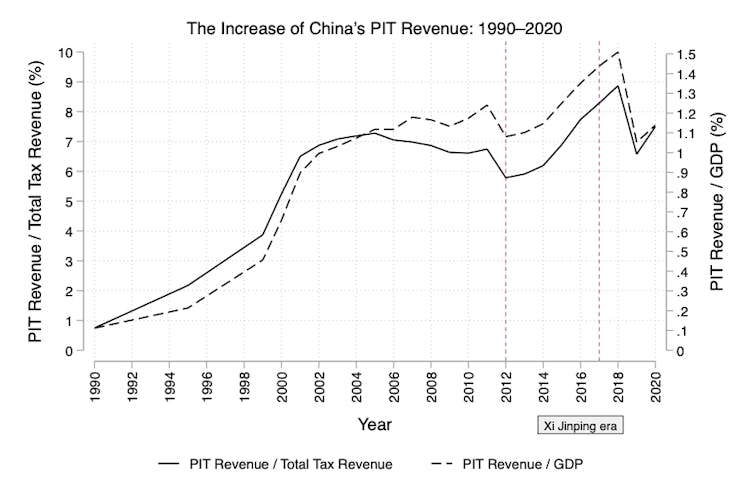

Many of these tax cuts delivered extraordinary benefits to China’s urban affluent. The 2018 amendment of the Personal Income Tax (PIT) Law, for example, dramatically raised exemptions, broadened rate brackets and introduced generous deductions.

The result is that many who comfortably belong to China’s top one per cent of income earners would still face a marginal tax rate of merely 10 per cent.

The 2018 PIT cut completely wiped out the gains in the PIT’s share of total revenue that had accrued in the previous six years.

Note that 2018 was after Xi entrenched his power at the 19th Party Congress and centralized much economic policy-making. This means the PIT cut cannot be pinned on anybody else — the decision to slash taxes for the rich was made by the small group of political leaders led by Xi.

Baked-in benefits

When reporting that Xi has launched a “common prosperity” campaign, the western media sometimes refers to the possible introduction of a property tax on personal residences.

In reality, even this proposed measure for “taxing the rich” has benefits for the rich baked in: property tax proposals discussed in the past decade all exempt primary residences.

But there is something even more interesting. China’s large PIT cut favoured the rich in 2018. The Chinese government has made large corporate income tax cuts since 2019. It repeatedly cut value-added tax (VAT) rates from 2016 to 2019. And it made a big payroll tax cut in 2020.

Chances are, not many outside China are aware that these tax cuts even happened. How, then, do we know so much about China’s tentative property tax increase? To see how odd this is, imagine Joe Biden’s proposal to raise taxes in the United States being greeted with lavish attention with scant mention that Donald Trump had significantly slashed those same taxes.

The explanation of this lopsided coverage is that public information about redistribution in China has come to depend on two highly unreliable sources.

The first is media catering to the affluent. Any possible tax increase will fuel debate. Tax cuts or policies that contribute to inequality, by contrast, aren’t as likely to be reported on.

The second source, of course, is the Chinese government. In 2021, these two sources are amplifying each other: when Xi claims to be interested in greater redistribution, regardless of whether he actually does, media for both China’s economic elite and the global investor class will talk it up.

Chinese tech is lucrative

After all, global financiers are enamoured with the outsized profits of Chinese tech companies; any government intervention that threatens to take away such windfalls is sensationalized to geopolitical proportions.

Much of the media hype about “common prosperity,” therefore, is not about redistributive policy in China at all. It might however reflect a search for narratives that would rationalize the Chinese government’s regulatory actions against some of its large publicly listed companies.

The force most responsible for lifting hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens out of poverty is probably globalization — which also reduced global inequality but exacerbated inequities in some advanced economies.

Discontent arising from the “China shock” — the economic impact of rising Chinese exports on the West — has led to a political backlash in the U.S. There is broad bipartisan agreement that China’s economic rise represents a threat to America. Lost in the heat of this sentiment, however, is the recognition that the welfare of 1.4 billion Chinese people may also hinge on China’s economic might.

In reality, China’s poor and middle class want the very same things as citizens in rich countries like the U.S. and Canada: cheaper housing and child care, more even distributions of education resources and help for the unemployed, sick and elderly.

Yet such Chinese desires are viewed with suspicion in the West. A public clamouring for such policies is more often portrayed as a challenge to China’s autocrats than a worthy demand for progress.

Xi’s egalitarian credentials are much weaker than the West pretends. But if China’s have-nots nurture hopes for a better future, they have no one else to look to.

Wei Cui, Professor of Law, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.