Technology

How rainbow colour maps can distort data and be misleading

The choice of colour to represent information in scientific images is a fundamental part of communicating findings. However, a number of colour palettes that are widely used to display critical scientific results are not only dangerously misleading, but also unreadable to a proportion of the population.

For decades, scientists have been pushing for a lasting change to remove such palettes from public consumption, but the battle over universal accessibility in science communication rages on.

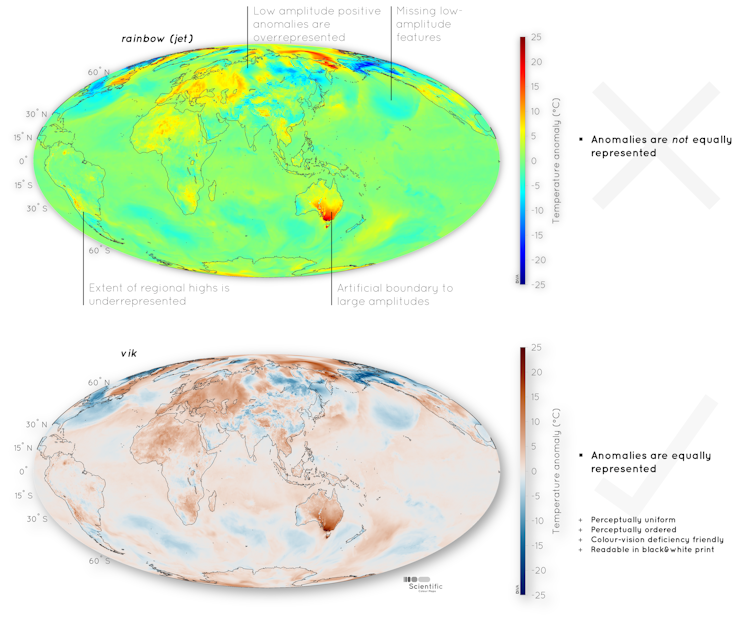

A colour map is a palette of multiple different colours that assign values to regions on a plot. An example of a misleading colour map is rainbow, which generally starts with blue for low values, then passing through cyan, green, yellow, orange, and finally red for high values. This colour combination is neither diverging, which would allow us to visually perceive a central value, nor sequential, which would make organizing values from low to high intuitive.

Colour brings life to data

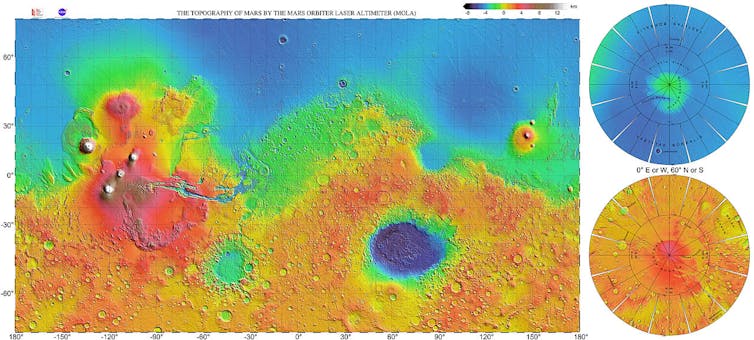

Using colour bar graphs can allow scientists to transform their collected data into something meaningful to be shared widely. This could be the first direct impression of a black hole, the mapping of votes cast in political elections, the planning of an expensive rover route on Martian topography, the essential communication of climate change or the critical diagnosis of heart disease.

Despite the clear importance of colour, scientists often choose the default palette setting of the visualization software that is being used.

Distorted data

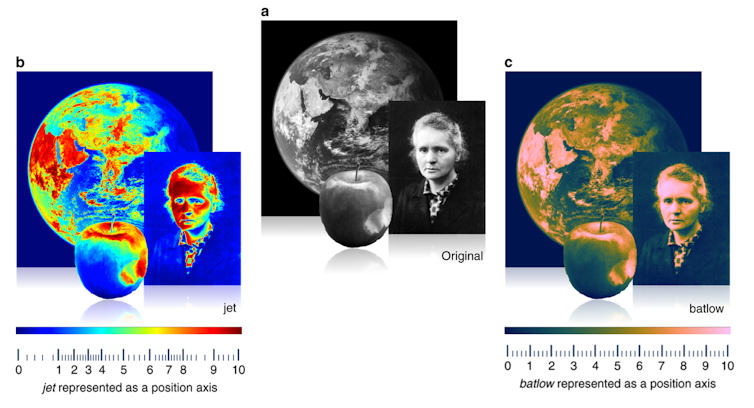

Rainbow — or jet — colour palettes are often the default setting on software, but the beautiful sweep of blue to red is misleading when displaying scientific data.

Fundamentally, the change between the colours in the palette is not smooth. For example, the change between blue and green and then between yellow and red occurs over a short distance. Vik and batlow, are examples of even colour palettes, where the colours change smoothly across the colour bar.

To put this into context, having a palette that changes between colours wildly is like having a position x or y axis with numbers that are not evenly spaced. In jet colour maps, this would be the equivalent of having numbers one to four close together and eight to 10 far apart. Such an uneven colour gradient means that certain parts of the palette would be naturally highlighted over others, distorting the data. The RGB colour space based on which such uneven colour gradients are created is mathematically simple, but not in tune with how we perceive colours and see the differences between them.

Inaccessible science

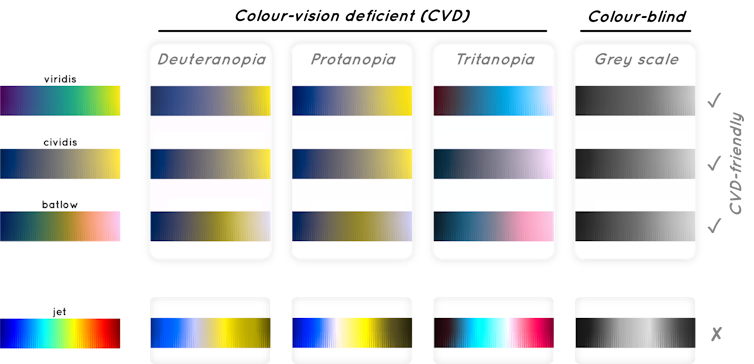

Another issue with an uneven colour palette like rainbow is that data presented using these colours may be unreadable or inaccurate for people with a vision deficiency or colour blindness. Colour maps that include both red and green colours with similar lightness cannot be read by a large fraction of the population.

The general estimate is that 0.5 per cent of women and eight per cent of men worldwide are subject to a colour-vision deficiency. While these numbers are lower and almost disappear in populations from sub-Saharan Africa, they are likely significantly higher in populations with a larger fraction of white people as, for example, in Scandinavia.

It is needless to state that scientific results should be able to viewed by as many people as possible, and such colour-vision deficiencies should be taken into account.

The winding road to the end of the rainbow

The issues with jet, rainbow and other uneven colour palettes have been known for years. Although certain fields of science have made significant changes to best practices on colour policy, other areas have stuck with their default settings.

As researchers interested in more effective data communication, we outline approaches that scientists can make to communicate their findings more efficiently: avoid using jet or rainbow default colour palettes; if it is necessary to use red and green, make sure they are not the same luminosity for accessibility; and use a palette that changes evenly between the colours.

There is growing recognition of the challenges associated with rainbow palettes. Some academic publications — like Nature Geoscience — have adopted a more even colour palette policy for new submissions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has colour-blind friendly guidelines for figures.

Software packages such as MATLAB and Python have removed rainbow as their default colour palette for data visualization features. However, old habits die hard and vigilance is still required — it is important to call out poor colour choices when noticed (otherwise the trends keep repeating).

Better science communication, better outcomes

The importance of accurately sharing scientific data in an accessible manner cannot be understated. Uneven colour gradients are often chosen to artificially highlight potential danger zones, such as the boundaries of a hurricane track or the current virus spread.

Decisions based on data being unfairly represented could produce, for instance, a Martian rover being sent over terrain that is too steep as the topography was inaccurately visualized, or a medical worker making an inaccurate diagnosis based on uneven colour gradients.

Accessible science for all starts with moving away from defaults. This can start with students learning to pick even colour gradients for term projects, to international publishers rejecting papers for misleading figures. One day, it may even include the Meteorological Service of Canada moving away from dramatic uneven palettes to highlight weather changes.

Fundamentally, using an inaccurate colour map is equivalent to a wilful misleading of the public by distorting data, and this has significant potential consequences.

Philip Heron, Assistant Professor, Environmental Geophysics, University of Toronto; Fabio Crameri, Researcher in geophysics, University of Oslo, and Grace Shephard, Research fellow, Geology and Geophysics, University of Oslo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.