News

Smoke seasons aren’t new but our efforts to control wildfires are — and should change

Like many people, I will remember this summer in shades of grey and red. As snapshots of a dull orange sun circulated social media, “zombie fires” rose from the Russian permafrost, entire towns were wiped off the map and Southern Europe became a scene of the apocalypse.

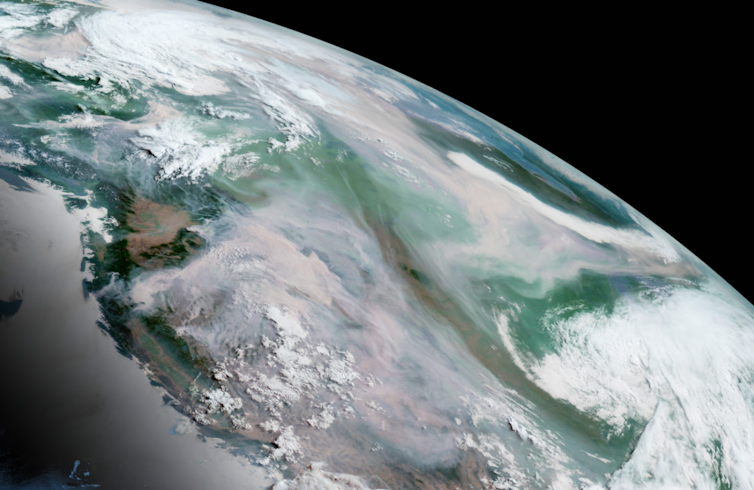

Satellites tracked enormous plumes of wildfire smoke across North America, the Atlantic Ocean and the Arctic Circle until they reached the North Pole.

Although the 2021 smoke season is in many ways unprecedented, smoke seasons themselves are not new. Western North America is particularly susceptible to smoke because Pacific winds carry it up and down the continent among active fire ecosystems in California, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia and Alaska.

Newspapers from 1926, 1945, 1958 and 1967 included complaints from British Columbians about the veil of smoke from forest fires. These were later corroborated by the layers of black carbon found in ice and sediment cores taken from glaciers and lake beds.

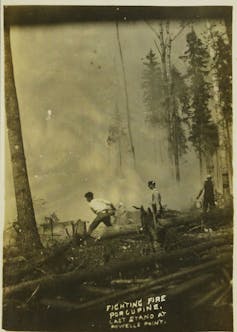

As an environmental historian, I use archival documents — photographs, forest service records, media accounts, oral interviews — to learn about large-scale smoke events in the past. In one of the best documented examples, smoke from an enormous fire in the Peace River district in northern British Columbia and Alberta choked the entire northern hemisphere in 1950. As the giant plume drifted east, it left a trail of anxious headlines behind it.

In New York: “Forest Fires Cast Pall On Northeast; Canadian Drift 600 Miles Long Darkens Wide Areas and Arouses ‘Atom’ Fears.” In Edinburgh: “Scots See Blue Sun, Fear End of World.” And in Oslo: “Solen og månen ble koboltblå!” (“The sun and the moon became cobalt blue!”). By October 1950, the smoke had circumnavigated the Earth.

If smoke seasons are not new, what makes this summer different?

Wildfire smoke difficult to regulate

Climate change makes wildfire seasons longer and more intense, but our checkered history of how we address smoke makes controlling it difficult.

Read more: How years of fighting every wildfire helped fuel the Western megafires of today

Before clean air regulations came into effect in Europe, Canada and the United States, industrial smoke was common in cities. Wildfire smoke was just one more pollutant in already grey skies. This was especially true for working class and racialized people, who often lived near smoke-producing factories.

During summer, wildfire smoke could make industrial smoke worse. In 1937, in an address to the annual conference of the Scottish branch of the National Smoke Abatement Society, John R. Currie, a professor of public health at Glasgow University, argued that wildfire smoke from Idaho had worsened industrial pollution for the cities in its path.

At the time, public health initiatives recognized that smoke was harmful, but there was little regulators could do about the smoke drifting out of the forests. Anti-pollution legislation and the introduction of new cleaner-burning fuels gradually reduced visible industrial pollution in most cities, but wildfire smoke remained a periodic problem.

Forests depend on fire

Historians have documented the long history of fire suppression in western North America. In British Columbia, the public believed that fire fighting technology would one day completely eliminate wildfire and smoke. For example, one of the first actions of the newly created Forest Service in British Columbia in 1912 was to create a permit system for burning.

“Slash burning” was still used to dispose of logging waste — the leftover tree limbs and other residues are called slash — but became tightly controlled. When slash fires escaped and burned communities, like the Gleneden fire of 1973, slash burning developed a negative reputation.

Over the years, experts proposed alternatives to burning such as chipping or cattle grazing to reduce landscape fuel, methods that had been used successfully elsewhere. However, the size and extent of Western Canada’s forests means slashing remains the primary method for clearing flamable logging waste, despite ongoing criticism.

We now know that western ecosystems require frequent, low-intensity fire to remain healthy and balanced. Decades of fire suppression has created more explosive and unpredictable conditions. Despite rapid advances in fire detection and fire fighting technology, fire seasons have gotten worse, not better.

Now experts are calling for more prescribed burns to restore fire to the land and mitigate modern smoke seasons. There is good scientific evidence to support them.

Read more: How Indigenous burning practices can help curb the biodiversity crisis

According to these experts, the question is not whether or not we should have smoke in the atmosphere, but when and how much of it we want to breathe. Yet most of places where forest fires pose the biggest threat have yet to implement prescribed burns on a wide scale. For example, the Prescribed Fire Council’s 2020 report shows that the American West lags behind the Southeast. Prescribed fire is not widely used in Southern Europe or Canada.

The future is smoky

Significant barriers remain to returning fire and smoke to our lives. In the past, people believed forest fire smoke was less harmful than industrial smoke. We now know that forest smoke poses significant health risks on par or worse than those of industrial smoke. Wildfire services, staffed largely by foresters and ecologists, are ill-equipped to make these kinds of public health decisions.

Climate change has made the decision to use prescribed fire more difficult. Although cultural or Indigenous burning promise a more holistic and inclusive approach to restoring fire to the land, colonial governments must avoid unloading the litigation and health risks of prescribed fire onto Indigenous communities, which already experience disproportionate impacts from wildfire and smoke.

Smoke seasons are not new, although climate change has exacerbated their scale and intensity. In planning for a smoky future, history shows how our responses to fire and smoke are cultural. Solutions like prescribed burning must take our historic relationship with fire and smoke into account.

Mica Jorgenson, Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Humanities, University of Stavanger

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.