Canada News

Ontario closes half of its youth detention centres, leaving some young people in limbo

In March, Ontario’s Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services closed 26 youth detention facilities, half of all facilities across the province. With an 81 per cent decrease in custody admissions over the past 15 years, many facilities were operating under capacity.

These closures come with $39.9 million in annual cost-savings. To date, the ministry has not indicated how they will reallocate these funds nor answered any questions about relocating youth from their communities and potential conflicts with current youth justice legislation.

In the same month, Ontario committed to redesigning the state guardianship system to better prepare youth aging out of care. Little has been said about what these two measures will mean for youth.

As a socio-legal scholar and a critical policy analyst who study carceral policy, we identify these decisions as a possible shift within the ministry to create more just outcomes for Ontario youth and their families. Yet transparency and strong commitments are needed. We call on the ministry to address concerns raised about the closures and to reallocate funds to an ethical reset of the state guardianship system.

Benefits of closures

We see the closure of the facilities as a positive development for two reasons. It indicates that the Youth Criminal Justice Act (YCJA) is working — meaning diversion and preventive measures are working. It also indicates a shift away from imprisoning criminalized youth.

The YCJA was created to reduce the over-reliance on custody for young people. The legislation stipulates that youth should only receive custodial sentences for the most severe crimes. This shift recognizes the lasting, devastating impact of confinement on young people.

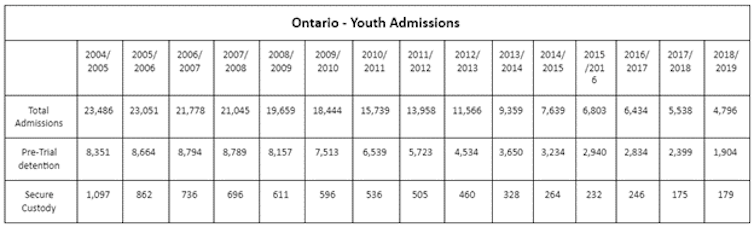

Since the YCJA came into effect in 2003, the number of youth in detention has steadily decreased. Specifically, there has been an 81 per cent reduction in the number of youth admitted to custody since 2004-05.

In five of the 26 facilities that were closed, no youth were admitted for the majority of 2019-20. A combination of legislative instruction, judicial restraint, pre- and post-charge diversion programs and preventive community programming explain this decrease. Together, these factors have helped keep youth out of custody and in communities.

Concerns about closures

The ministry’s lack of transparency around the closures is cause for concern for three reasons.

1. Location: Transporting youth far from their communities

Nearly half of the youth imprisoned in Canada are Indigenous. In 2018, Indigenous youth represented 8.8 per cent of the population in Canada but represented 43 per cent of youth admissions to youth detention in 2018-19.

Facility closures were abrupt and little consultation was done with stakeholders. Ten of the 26 facilities that closed were located in Northern Ontario. Grand Chiefs have condemned the sudden closures. Nishnawbe Aski Nation Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler said:

“We all thought, you know, the days of seeing our kids forcibly removed and shackled and sent away to faraway places away from their families and loved ones, and their communities and their homes were behind us. But obviously, that’s not the case.”

The closures resulted in youth being relocated far from their communities with little notice. Elders explained that these children have already experienced trauma, and the move far away from their families contributes to that trauma. In the 1990s, Canada shifted toward regional federal prisons for women under the rationale that it better supported rehabilitation and reintegration by having them located closer to their families and communities.

2. Conflicts with the YCJA

The majority of youth who spend time in detention are waiting for a bail hearing or pending trial: while there were 179 admissions to custody in Ontario in 2018-19, there were nearly 2,000 youth held in pre-trial detention.

A recent report by the John Howard Society of Ontario indicates the majority of these youth are poor and racialized, specifically young men who are Black (15.3 per cent) and Indigenous (8.7 per cent). Given that the turnaround time between arrest and bail hearings is short, the province may see an increased use of adult facilities to detain youth who have been arrested.

It is not clear whether youth will be kept in pre-trial detention at local adult facilities or transported to distant youth facilities. Both options – confining youth with adults or relocating them and cutting them off from their support networks – pose conflicts with the mission of the YCJA.

In the case of Ashley Smith, only a few months after her 18th birthday, she was transferred to an adult prison after spending nearly five years in the youth detention system in New Brunswick. Smith was frequently moved between institutions during this time, and held in administrative segregation. Her mental health deteriorated under these conditions. Smith died at Grand Valley Institution for Women in October 2007.

3. COVID-19

Though few youth were relocated in March, we do not know the number of youth that are currently confined in facilities across the province. Amid the pandemic, community members have called for decarceration.

Moving youth into more populated facilities does not align with public health directives and calls from health professionals.

Investing in youths’ futures through an ethical reset in child welfare

Tamara Stone, director of the Strategic Innovation and Modernization Branch with the ministry’s Youth Justice Division says in response to questions from the authors:

“The decision to close youth justice facilities in Ontario is not related to the ministry’s current work underway to develop a more responsive youth transition framework.”

This response suggests that youth detention and state guardianship are siloed programs at the ministry. Yet, children in state guardianship have a higher likelihood of criminalization and of reoffending than those who live with their families.

Youth detention and state guardianship are interconnected.

Read more: COVID-19 leaves youth forced out of foster care even more vulnerable

Researchers like Youngmin Yi (sociology) and Christopher Wildeman (policy analysis and management) have long recognized the overlap between the carceral and state guardianship systems. One report written in British Columbia approximates one-third of youth who leave state guardianship are criminalized.

In an Office of the Correctional Investigator study with imprisoned young adults, 25 per cent of those interviewed were from foster and group homes. Many who experienced time in foster or group homes described their experience as negative with little stability, support or assistance. Some youth have even called group homes gateways to jail.

The ministry’s approach must centre the relationship between systems. Instead of shifting resources into more carceral programs for young people, the ministry must reallocate funds further embracing decarceration and developing the readiness model that would help transform the lives of youth leaving state guardianship.

Eliminating arbitrary age cut-offs is not only about giving youth more time. It is also about improving the futures of young people who have been pushed to the margins through no fault of their own.

Eva Marszewski, Director of Peacebuilders Canada, says in response to a questioning from the authors:

“Based upon research in the neuroscience and psychology of the developing brain, a policy on adolescence would recognize that a holistic, developmental approach, combined with a restorative philosophy of justice, is optimal in addressing, managing and redirecting challenging adolescent behaviour and conflict.”

The evidence is clear. Young people leaving the state’s guardianship should be met with caring, not criminalizing, responses.

Marsha Rampersaud, PhD Candidate, Sociology, Queen’s University, Ontario and Linda Mussell, PhD, Political Science, Queen’s University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.