Education

To ‘future proof’ universities, leaders have to engage faculty to make tough decisions

Universities are at a crossroads, with COVID-19 acting as a tipping point for whether they thrive or barely survive.

On April 13, about 100 faculty members from Laurentian University lost their jobs because of a massive restructuring and insolvency negotiations. In Australia this past fall, University of Sydney eliminated 10 faculties and 100 programs in order to increase its long-term sustainability.

Demographic, technological and socio-economic trends, including reduced government funding and increased dependency on private donors, are influencing the mandate of universities, and survival depends on transformation. As we document in our recent book, these trends are affecting all universities across the west, and most institutions are unable to nimbly pivot to the new reality.

Our research shows universities must “future proof” themselves, which happens when an institutional strategy is focused on the future while mitigating the impact of unforeseen events. Successful future-proofing involves clearly articulating a path to a new vision with the participation of faculty, staff and external community members. It also involves consistently applying decision-making criteria and continuously measuring progress.

Attracting students

Virtual technologies have been available for decades, but universities at large were mostly dependent on in-person learning. Online classes comprised only two per cent of the global higher education market before the pandemic, but as universities were forced to close, most classes were driven online in a matter of weeks.

Most faculty expect to return to traditional teaching, with few questioning its value. Yet the effectiveness of large lectures continues to be questionable, while small group face-to-face discussion leads to greater learning. Post-pandemic universities must integrate face-to-face time with virtual technologies to optimize learning.

Universities have increasingly been forced to compete for students from a declining applicant pool. Highly ranked universities with excellent online programs can attract students globally. Demand is increasing for professionally oriented degrees. Universities Canada notes liberal arts enrolment at Canadian universities has declined in recent years.

Facebook, Google certificates

Private companies are a new competitor as they provide micro-credentials for employment relevant skills. Examples include Google’s recent announcement of three “career certificate programs,” and Facebook’s partnership with colleges to deliver marketing certificates. These companies can create programs faster and at a lower cost than universities. In order to maintain integrity and competitiveness, universities must revise programs to balance short- and long-term educational needs.

Public universities, in developed countries, can no longer depend on government funding, and must restructure to reduce costs and increase revenue.

An increasing trend is to link government funds to visible performance metrics, which has led some research universities to redirect resources to commercialized research.

Universities are competing for limited philanthropic donations with donors expecting greater scrutiny on how their funds are spent. Donor restrictions reduce the flexibility of university leaders to redirect funds to less visible but important needs or programs.

Read more: Universities eye philanthropic funds but experts warn of risks

As a result, both government and philanthropic funding are increasingly influencing how programs develop. University leaders are scrambling to find the appropriate balance between independent development and responsiveness to funders.

Tension between faculty views, realities

Based on our own experiences as strategic planners in universities, we have found that many tenured faculty remain convinced the traditional university structure provides the greatest value to society, and most universities are constrained by their extensive physical and technical infrastructures.

Universities may survive in their current state, but they will lose legitimacy and perceived value if they don’t adapt. And other organizations will quickly move in to replace them.

Read more: Stop telling students to study STEM instead of humanities for the post-coronavirus world

The surviving institutions will have made tough decisions that will include closing programs and departments, and creating new approaches to delivering programs while still building critical thinking and judgment in students. In terms of research, the university will have to balance supporting curiosity-driven research and research that can be commercialized, including research focused on pressing societal and environmental issues.

How will universities survive the disruption?

Almost all universities engage in strategic planning, but the actual plans rarely move beyond presidents’ offices or are viewed by faculty as “window dressing.”

In contrast, future-proofing occurs when a strategic plan is the primary co-ordination point for difficult trade-offs and decisions. Universities are comprised of semi-autonomous operating units, with important information on the impact of trends dispersed across them. Stakeholders like faculty, staff and external community members are aware of some trends, but few have sufficient information to understand their full impact on the institution’s future.

Difficult decisions, transparent criteria

A critical first step in developing a strategy is coalescing this dispersed information into digestible formats that all administrators, faculty, staff and community members can access.

Once faculty and staff have a more complete understanding of the disruptions, their recommendations are more focused on a sustainable future for the university, rather than just their department. Finalizing the strategy is the responsibility of university leaders, however they must ensure that all faculty and staff understand its intended outcomes.

A strategy provides a line-of-sight between the desired future state, the development or cancellation of programs, attracting and allocating funds and how the university will measure the impact of decisions.

Difficult decisions must be based on transparent and consistent criteria, and visible benchmarks must be monitored to assess progress towards strategic goals. Resistance decreases when stakeholders understand the basis of a decision, perceive consistency in the criteria applied across decisions and recognize progress towards goals.

Universities without a visible strategy will not flourish and may not even survive. Although the preceding discussion may suggest creating a strategy is easy, it is not. If it was easy, very few businesses would fail. The probability of successful future-proofing dramatically increases when university leaders appropriately engage stakeholders in forming strategies.

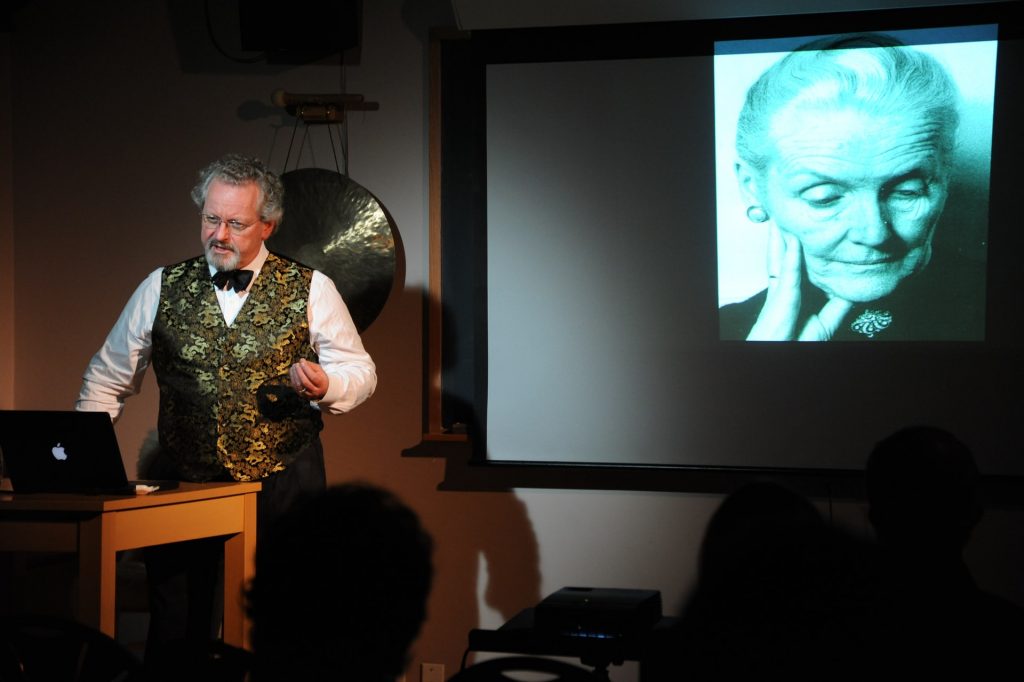

Loren Falkenberg, Senior Associate Dean, Business, University of Calgary and M. Elizabeth Cannon, President Emerita, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.