Canada News

Ottawa’s latest climate plan bets on expensive and unproven carbon capture technologies

What about Prime Minister Trudeau’s promise to plant two billion trees? Planting trees is, after all, a natural method of carbon capture and storage. (File Photo: Justin Trudeau/Facebook)

Last week, the federal government released its long awaited plan to tackle greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. Bill C-12, if passed, commits Canada to “binding” targets every five years as of 2030 with the goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

The bill is thin on details, due to its focus on establishing an independent 15-member advisory board. This is both a strength, in that it will hopefully include climate scientists, Indigenous people and other expert stakeholders, and a weakness, because it pushes the timeline for specific measures and action further into the future, with 2030 the first target date.

What is most concerning is that by dragging its feet on specific measures to curb greenhouse gas emissions, the Trudeau government is shoehorning Canadians into expensive, unproven and unreliable technologies.

As a researcher who studies the governance of climate-altering technologies (such as carbon capture and storage), I can assure you that we are already behind on tackling climate change and catching up is going to be expensive. The government’s strategy will likely rely upon technology that isn’t viable in the way it hopes.

Staying on target

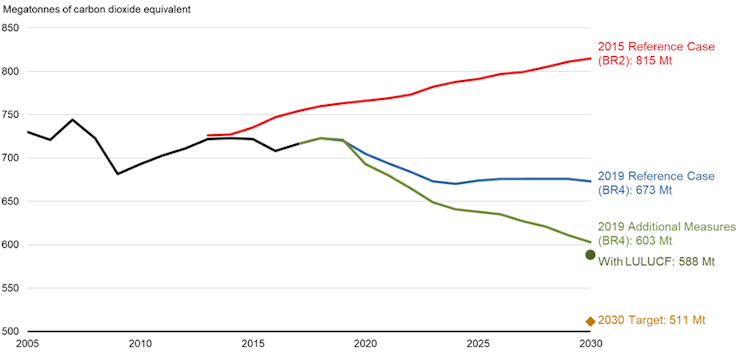

Canada has repeatedly failed to meet any of the climate targets it has set in place since 1992. This has left us further behind our Paris climate agreement targets and scrambling to catch up to meet our global commitments.

Not only do we need to meet these climate targets this time around — our international trade partners such as the EU and even China may see us as laggards, further eroding our international credibility — we need to make up for lost time.

The focus of the federal government is on market-driven solutions, including technologies that remove carbon from the air or emissions and lock them away. But carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) are not silver bullets in the fight against climate change.

(Environment and Climate Change Canada)

Canada is home to some of the most successful CCS projects and companies in the world, including the Alberta Carbon Trunk Line, Boundary Dam and Carbon Engineering. However, these are expensive demonstration projects. Their use could be targeted to specific sectors (such as aluminium manufacturing), but they will never effectively reduce Canadians’ emissions at scale.

Capturing and storing carbon is expensive, and in some cases outright ineffectual. The United States government spent US$5 billion from 2010 to 2018 on the technology, but it would take additional significant investments, more research and some technological breakthroughs for the technology to lower the cost of capturing carbon to US$94-232 per tonne. This is staggering compared to Canada’s baseline carbon tax of $50 per tonne of emissions by 2022, and when factored into the already low price of Canadian oil, we are are left with a most unhappy conclusion.

Who is paying for this?

Typically, companies would pay taxes or levies over time into various programs to pay for negative externalities — the side effects of products or systems they run that cause social, economic or environmental harms. These funds would then be used to pay for those associated costs.

This solution is dubbed “Pigouvian taxation” (after Arthur Pigou). Ireland, for example, introduced a plastic bag tax (as opposed to banning them), which resulted in a 90 per cent decrease in their use.

The problem is that in Canada companies are not paying into any such funds — nor have they — leaving Canadians with no source to pay for this new expense.

So how would Canada find the money to pay for expensive projects such as carbon capture and storage? As it stands, that cost will be passed to the taxpayer. Our current carbon tax circulates the money back into the economy.

Two billion trees

What about Prime Minister Trudeau’s promise to plant two billion trees? Planting trees is, after all, a natural method of carbon capture and storage.

Planting trees is a useful short-term exercise, but trees don’t live forever. Although the soil in boreal forests contains carbon stored there generations ago, it can be released by logging or forest fires, which are getting more severe due to climate change. These types of changes, if not properly managed, can lead to forests becoming carbon sources.

In addition, the darkness of leaves can absorb more incoming energy than the potentially lighter ground surface. Planting trees over areas that would otherwise be snow covered, could actually warm the planet while still absorbing carbon, though more analysis is necessary to understand this issue.

This is not to say that carbon capture and storage or carbon dioxide removal technologies do not have a role to play in the future. Concrete produces four to eight per cent of global emissions, and mandating that all concrete facilities be fitted with carbon capturing technologies could reduce their emissions. While these are expensive, they may be necessary.

Even if the technology were applied to the energy sector, Canadian oil would likely be a net loss on every barrel produced — and who would pay for the cost of moving it to widespread use? The federal government is still reeling from the cost of the Trans Mountain pipeline, the private sector has no appetite to invest in such a venture without guarantees of profitability and despite claims of well-financed conspiracy, environmental groups aren’t exactly flush with cash.

The current Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) models rely on the deployment of significant amounts of carbon capture and storage in the latter part of the century to meet agreed-upon targets. To rely upon such technologies as a silver bullet for addressing Canadian climate policy, however, is flawed and doomed to fail. When the Government of Canada releases precise details for meeting the climate targets outlined in Bill C-12, it cannot rely upon carbon capture and storage or carbon dioxide removal if there is any hope in succeeding.![]()

Burgess Langshaw Power, PhD Student, Global Governance program at the Balsillie School for International Affairs, University of Waterloo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.