Lifestyle

Who invented the Electoral College?

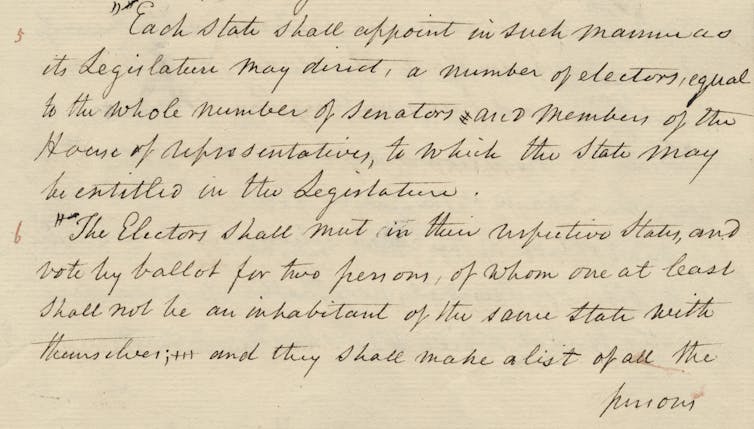

U.S. National Archives, CC BY-NC-ND

The delegates in Philadelphia agreed, in the summer of 1787, that the new country they were creating would not have a king but rather an elected executive. But they did not agree on how to choose that president.

Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson called the problem of picking a president “in truth, one of the most difficult of all we have to decide.” Other delegates, when they later recounted the group’s effort, said “this very subject embarrassed them more than any other – that various systems were proposed, discussed, and rejected.”

They were at risk of concluding their meetings without finding a way to pick a leader. In fact, this was the very last thing written into the final draft. Had no agreement been reached, the delegates would not have approved the Constitution.

I am a civics educator who has also run Purdue University’s Constitution Day celebration for 15 years, and one lesson I always return to is the degree to which the founders had to compromise in order to ensure ratification. Selecting the president was one of those compromises.

Three approaches were debated during the Constitutional Convention: election by Congress, selection by state legislatures and a popular election – though the right to vote was generally restricted to white, landowning men.

Howard Chandler Christy/Architect of the Capitol

Should Congress pick the president?

Some delegates at the Constitutional Convention thought that letting Congress pick the president would provide a buffer from what Thomas Jefferson referred to as the “well-meaning, but uninformed people” who, in a nation the size of the United States, “could have no knowledge of eminent characters and qualifications and the actual selection decision.”

Others were concerned that this approach threatened the separation of powers created in the first three articles of the Constitution: Congress might choose a weak executive to prevent the president from wielding veto power, reducing the effectiveness of one of the system’s checks and balances. In addition, the president might feel indebted to Congress and yield some power back to the legislative branch.

Virginia delegate James Madison was concerned that giving Congress the power to select the president “would render it the executor as well as the maker of laws; and then … tyrannical laws may be made that they may be executed in a tyrannical manner.”

That view persuaded his fellow Virginian George Mason to reverse his previous support for congressional election of the president and to then conclude that he saw “making the Executive the mere creature of the Legislature as a violation of the fundamental principle of good Government.”

The Conversation, from Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-ND

Letting state lawmakers choose

Some delegates thought getting states directly involved in picking the leader of the national government was a good approach for the new federal system.

But others, including Alexander Hamilton, worried that states would select a weak executive, to increase their own power. Hamilton also observed that legislators are often slower to move than top leaders might be expected to: “In the legislature, promptitude of decision is oftener an evil than a benefit.”

It’s not as pithy as the musical, perhaps, but the point is clear: Don’t trust the state legislatures.

Power to the people?

The final approach debated was that of popular election. Some delegates, like New York delegate Gouverneur Morris, viewed the president as the “guardian of the people,” whom the public should elect directly.

The Southern states objected, arguing that they would be disadvantaged in a popular election in proportion to their actual populations because of the large numbers of enslaved people in those states who could not vote. This was eventually resolved – in one of those many compromises – by counting each enslaved person as three-fifths of a free person for the purposes of representation.

George Mason, a delegate from Virginia, shared Jefferson’s skepticism about regular Americans, saying it would be “unnatural to refer the choice of a proper character for chief Magistrate to the people, as it would, to refer a trial of colours to a blind man. The extent of the Country renders it impossible that the people can have the requisite capacity to judge of the respective pretensions of the Candidates.”

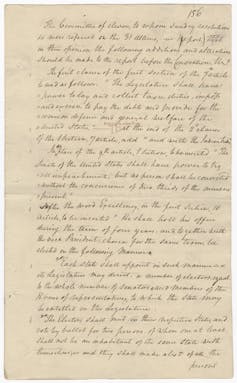

U.S. National Archives

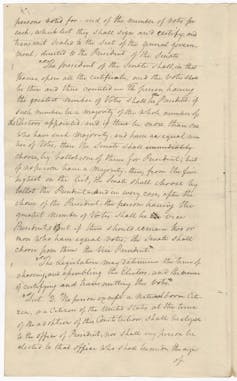

U.S. National Archives

11 left to make the decision

The delegates appointed a committee of 11 members – one from each state at the Constitutional Convention – to solve this and other knotty problems, which they called the “Grand Committee on Postponed Questions,” and charged with resolving “unfinished business, including how to elect the President.”

At the beginning, six of the 11 members preferred national popular elections. But they realized they could not get the Constitution ratified with that provision: The Southern states simply would not agree to it.

Between Aug. 31 and Sept. 4, 1787, the committee wrestled with producing an acceptable compromise. The committee’s third report to the Convention proposed the adoption of a system of electors, through which both the people and the states would help choose the president. It’s not clear which delegate came up with the idea, which was a partly national and partly federal solution, and which mirrored other structures in the Constitution.

Popularity and protection

Hamilton and the other founders were reassured that with this compromise system, neither public ignorance nor outside influence would affect the choice of a nation’s leader. They believed that the electors would ensure that only a qualified person became president. And they thought the Electoral College would serve as a check on a public who might be easily misled, especially by foreign governments.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

But the original system – in which the winner of the Electoral College would become president and the runner-up became vice president – fell apart almost immediately. By the election of 1800, political parties had arisen. Because electoral votes for president and vice president were not listed on separate ballots, Democratic-Republican running mates Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied in the Electoral College, sending the contest to the House of Representatives. The House ultimately chose Jefferson as the third president, leaving Burr as vice president – not John Adams, who had led the opposing Federalist party ticket.

The problem was resolved in 1804 when the 12th Amendment was ratified, allowing the electors to cast separate ballots for president and vice president. It has been that way ever since.![]()

Phillip J VanFossen, J.F. Ackerman Professor of Social Studies Education; Director, Ackerman Center; Associate Director, Purdue Center for Economic Education, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.