Canada News

Nova Scotia lobster dispute: Mi’kmaw fishery isn’t a threat to conservation, say scientists

In the summer, lobster molt and their shells are soft, resulting in a lower quality lobster. (File photo: @photocapebreton/Unsplash)

In mid-September, the Sipekne’katik First Nation launched a moderate livelihood lobster fishery along the coast of southwestern Nova Scotia. Its fishers set out an estimated 250 traps at the time, the equivalent of one commercial boat.

Some, including the commercial fishing sector, worried this new fishery was a threat to maintaining healthy lobster stocks. Commercial fishers have articulated two conservation concerns about the Sipekne’katik fishery: its scale and whether fishing during the summer season — when lobsters molt and their shells are soft — is a problem for the survival of lobsters that are thrown back.

As a researcher with expertise in fisheries science, fisheries economics and marine policy, I see no evidence the fishery will harm lobster stocks. Conservation is not at the heart of the ongoing dispute.

Inherent and treaty rights

Mi’kmaq have inherent rights to practise their traditions and customs, including fishing. Under the Peace and Friendship Treaties signed in the 1700s, codified in the Constitution under Section 35 and reaffirmed by the Supreme Court, Mi’kmaq have a right to harvest fish for food, social and ceremonial purposes and a right to fish for a moderate livelihood.

Yet two decades later, there has been no clarity on what “moderate livelihood” means, nor how implementation of the treaty right should unfold. Great people have been working on it, but it is not a trivial question.

Others have as well, including Listuguj and Potolek First Nations.

The protests over the Mi’kmaw fishery have escalated to acts of vandalism and violence. The message from commercial fishers is that fishing in St. Marys Bay outside the commercial season is illegal and a conservation concern. In fact, it is neither.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) did not immediately help the situation. Fisheries Minister Bernadette Jordan and Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett waited five days to make an explicit statement that it was, in fact, a legal fishery. By that time, the commercial sector’s view became further entrenched.

Conservation concerns unfounded

The commercial lobster season in Lobster Fishing Area 34, where the bay is located, runs from late November to late May. The livelihood fishery was launched outside that, leading the commercial harvesters to label it as illegal. Yet, as Shelley Denny, a Mi’kmaw doctoral student at Dalhousie University, points out, there are two sets of rules for Indigenous and non-Indigenous fish harvesters. The Indigenous fishery is not illegal, but is it a conservation concern?

(Brandon Maloney), Author provided

Initially, five Sipekne’katik vessels were fishing 50 traps per vessel; there are now reportedly 10 vessels fishing a total of 500 traps. Compare that to the commercial sector, where each vessel — there are about 100 fishing in the bay — is allowed to fish 350 traps, for a total of about 35,000 traps.

There is no reason, no science, to suggest that the equivalent of one or two commercial vessels fishing in St. Marys Bay will be problematic. Lobster biologist Robert Steneck would bet you a beer there will be no negative impact on the lobster population.

Fisheries scientists and managers need only look to our neighbour to the south, Maine, which operates a year-round lobster fishery. In the summer, lobster molt and their shells are soft, resulting in a lower quality lobster. The Canadian market doesn’t prioritize these lobsters, even though Maine does.

These lobsters are more susceptible to what’s called “post-release mortality,” meaning that those lobsters that cannot be kept — lobsters that are too small or females bearing eggs, for example — are thrown back and may not survive. This mortality needs to be accounted for, but it doesn’t mean it’s not sustainable to fish during the summer.

Normal catches

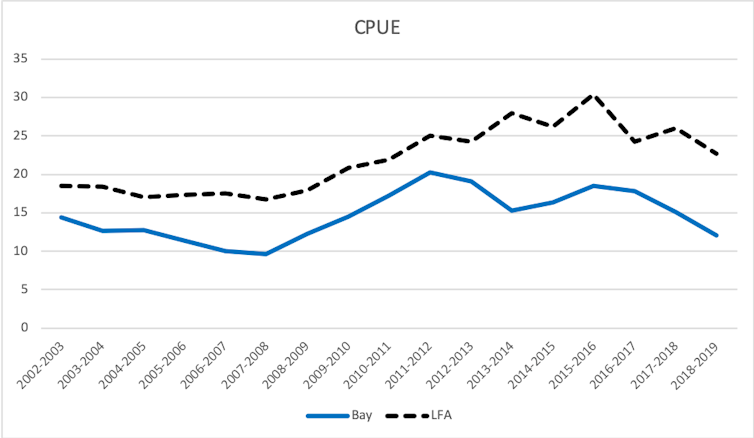

One index fisheries scientists use to measure the status of a resource is called catch per unit effort (CPUE). In this case, lobster is the unit and the effort invested is one vessel.

While not perfect, the CPUE represents a relative abundance of lobster in a given area. When CPUE falls, it may be a sign that fewer lobsters are available in that particular area, but may or may not signal that the population as a whole may be in trouble.

Data for St. Marys Bay and Lobster Fishing Area 34 show that commercial catches have declined the past two years compared to the 2015-16 season. Commercial fishers have argued this is due to the summer “food, social and ceremonial” fishery that operates outside the commercial season.

The recent protests have targeted the “livelihood” fishery, but it seems that what the commercial sector is actually angry about is the food, social and ceremonial fishery. According to Brandon Maloney, fisheries director for Sipekne’katik, the band developed their plan for this fishery twenty years ago — this is not a new development.

So, what does the CPUE for St. Marys Bay look like over the past 16 years? I took the data released by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and calculated it. Although the CPUE in the past two years are on the lower end of the range, they are clearly within it. And they really only seem low when compared to the highs recorded in 2015-16.

(Author provided. Data from DFO, September 2020.)

The assertion that the drop in bay catches is a conservation concern is wrong, as DFO itself has stated. So if there is no conservation concern, then the assertion that Indigenous summer food fisheries are decimating the stocks, as the commercial sector has argued, is incorrect.

It’s not surprising that commercial fishers are upset by a decrease in lobster landings in St. Marys Bay. But my assessment of the fishery is not why the public has a poor view of the group.

Their behaviour has been abhorrent. The sector needs to address its racism, cease its vigilantism, support dialogue and ensure that its positions are grounded in evidence. And, as Denny argues, it must make room for the livelihood fishery. The rest of Canada — and the world — is watching in shame. We must do better.![]()

Megan Bailey, Associate Professor, Canada Research Chair, Integrated Ocean and Coastal Governance, Dalhousie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.