News

South Africa’s TB, HIV history prepares it for virus testing

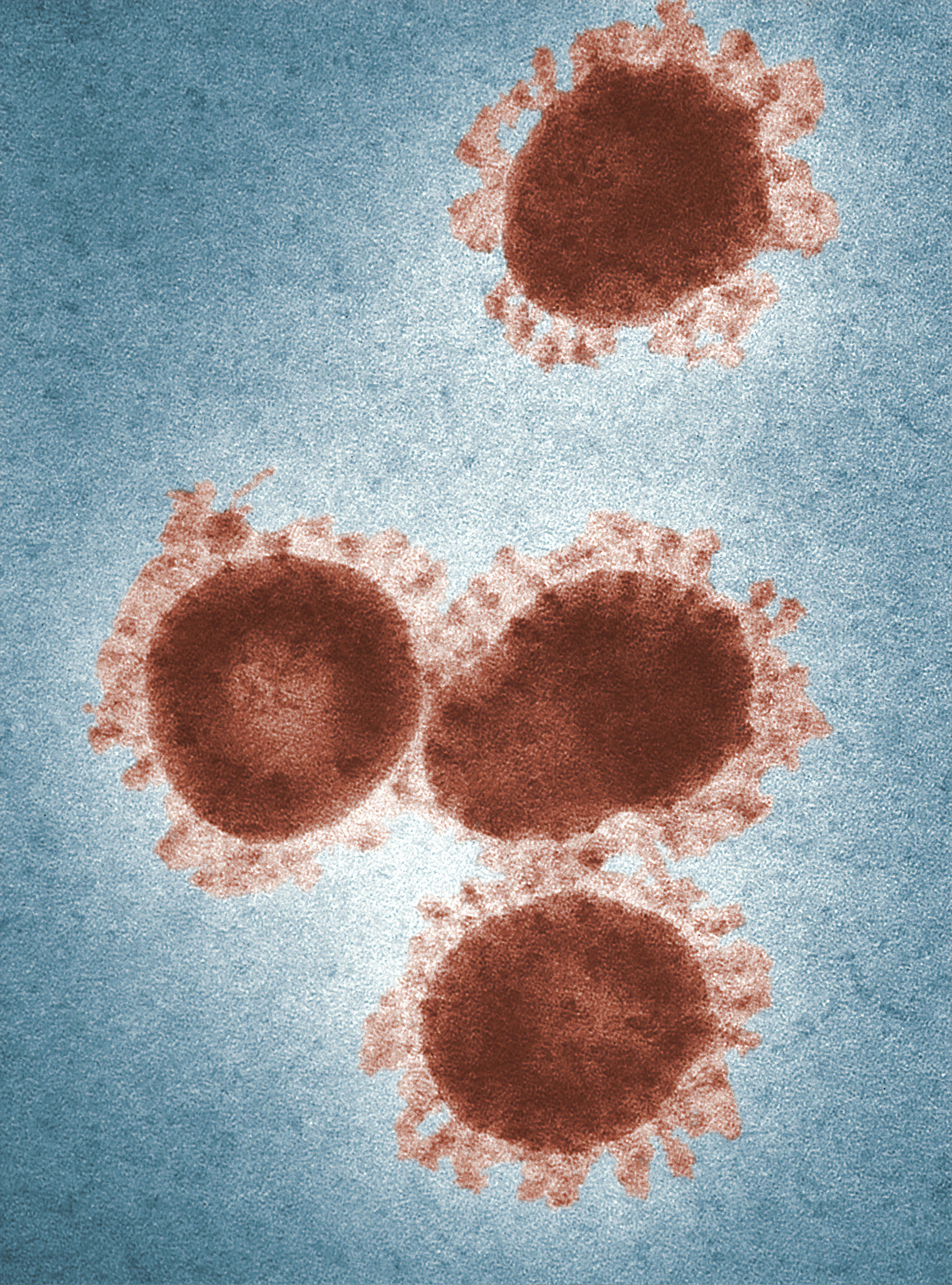

Health experts stress that the best way to slow the spread of the virus is through extensive testing, the quick quarantine of people who are positive, and tracking who those people came into contact with. (File Photo by CDC/Unsplash)

JOHANNESBURG — South Africa, one of the world’s most unequal countries with a large population vulnerable to the new coronavirus, may have an advantage in the outbreak, honed during years battling HIV and tuberculosis: the know-how and infrastructure to conduct mass testing.

Health experts stress that the best way to slow the spread of the virus is through extensive testing, the quick quarantine of people who are positive, and tracking who those people came into contact with.

“We have a simple message for all countries: test, test, test,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization and a former Ethiopian health minister, said recently.

South Africa has begun doing just that with mobile testing units and screening centres established in the country’s most densely populated township areas, where an estimated 25% of the country’s 57 million people live.

Clad in protective gear, medical workers operate a mobile testing unit in Johannesburg’s poor Yeoville area. In the windswept dunes of Cape Town’s Khayelitsha township, centres have been erected where residents are screened and those deemed at risk are tested.

While most people who become infected have mild or moderate symptoms, the disease can be particularly dangerous for older people and those with existing health problems, such as those whose immune systems are weakened or who have lung issues. That means many in South Africa — with world’s largest number of people with HIV, more than 8 million, and one of the world’s highest levels of TB, which affects the lungs — are at high risk of getting more severe cases of the disease.

“Social distancing is almost impossible when a large family lives in a one-room shack. Frequent hand-washing is not practical when a hundred families share one tap,” said Denis Chopera, executive manager of the Sub-Saharan African Network for TB/HIV Research Excellence.

“These are areas where there are high concentrations of people with HIV and TB who are at risk for severe symptoms. These are areas that can quickly become hot spots,” said Chopera, a virologist based in Durban.

But years of fighting those scourges has endowed South Africa with a network of testing sites and laboratories in diverse communities across the country that may help it cope, say experts.

“We have testing infrastructure, testing history and expertise that is unprecedented in the world,” said Francois Venter, deputy director of the Reproductive Health Institute at the University of Witswatersrand. “It is an opportunity that we cannot afford to squander.”

The country imposed a three-week lockdown March 27 that bought it some time, said Venter.

“Now is the time to test and track. We must get out into the community and find out where the hot spots are,” said the doctor. “With testing we can strategically focus our resources.”

South Africa was one of only two countries in Africa that could test for the new coronavirus when it began its global spread in January. Now at least 43 of the continent’s 54 countries can, but many have limited capacity.

Widespread testing has even been a challenge in North America and Europe, where some countries with large outbreaks resorted to only testing patients who are hospitalized.

Currently able to conduct 5,000 tests per day, South Africa will increase its capacity to more than 30,000 per day by the end of the April, according to the National Health Laboratory Service.

That would make its capacity among the best in Africa and comparable to many countries in the developed world, say health experts.

At first in South Africa, COVID-19 appeared to be a disease of the rich, as the first few hundred cases were virtually all people who had travelled to Italy and France and who could afford to go to private clinics.

But as local transmission of the virus takes hold, the public health service must take testing into the country’s most vulnerable areas: the overcrowded, under-resourced townships.

South Africa has thousands of community health workers experienced in reaching out in these areas to educate about infectious diseases as well as to screen, test and track contacts to try to contain the spread.

South Africa is already testing by taking swabs and using conventional means.

And it is also expecting to receive new kits that will allow rapid test results. South Africa has for several years been using a TB testing system that extracts genetic material and produces results within two hours. That system, known as GeneXpert, has developed a test for COVID-19 that was approved last month by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and South Africa is expecting delivery of those test kits within weeks.

“This will dramatically shorten our testing time, and the smaller machines can be placed in mobile vehicles, which are ideal for community testing,” said Dr. Kamy Chetty, CEO of the National Health Laboratory Service.

South African Health Minister Zweli Mkhize said the country must find out “what is happening in our densely populated areas, in particular the townships” where he said health workers would “continue to venture forth in full combat by proactively conducting wall-to-wall testing and find all COVID-19 affected people in the country.”