Entertainment

Don Rickles, king of insult comedy, dies at 90

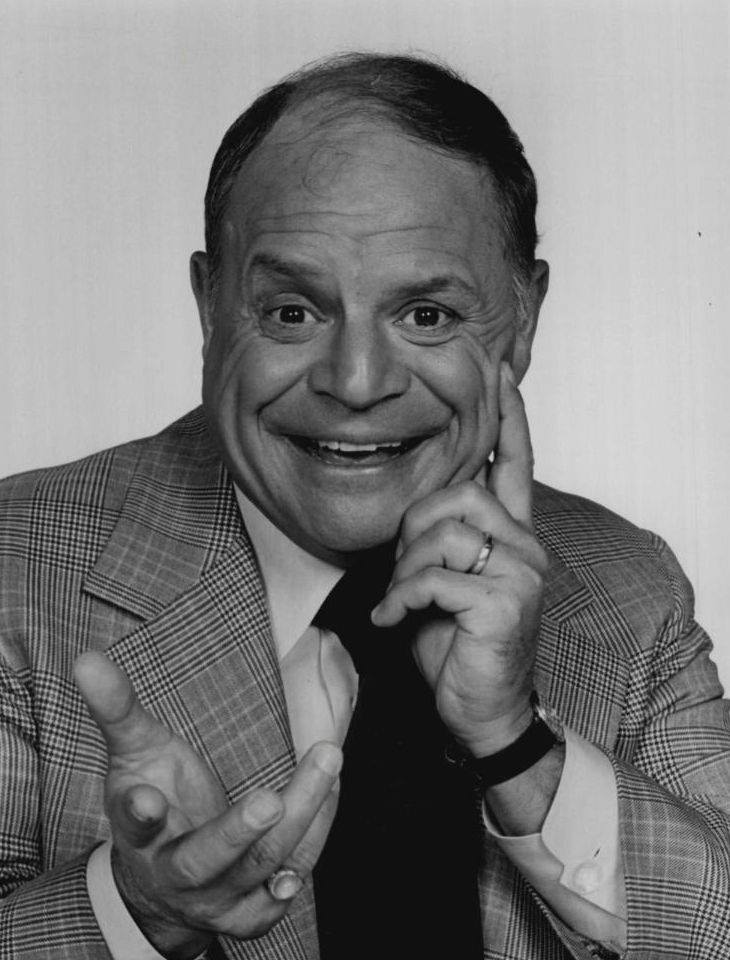

Don Rickles, the big-mouthed, bald-headed “Mr. Warmth” whose verbal assaults endeared him to audiences and peers and made him the acknowledged grandmaster of insult comedy, died Thursday. He was 90. (Photo: Iconic Cool/Facebook)

LOS ANGELES — Don Rickles, the big-mouthed, bald-headed “Mr. Warmth” whose verbal assaults endeared him to audiences and peers and made him the acknowledged grandmaster of insult comedy, died Thursday. He was 90.

Rickles, who would have been 91 on May 8, suffered kidney failure and died Thursday morning at his home, said Paul Shefrin, his longtime publicist and friend.

For more than half a century, Rickles headlined casinos and nightclubs from Las Vegas to Atlantic City, New Jersey, and livened up late-night talk shows. No one was exempt from Rickles’ insults, not fans or presidents or such fellow celebrities as Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Johnny Carson.

Even volatile Sinatra let Rickles have his comedic way with him.

“Hey, Frank, make yourself at home. Hit somebody,” Rickles snapped at the singer attending his show. Sinatra laughed.

Despite jokes that from other comics might have inspired boycotts, he was one of the most beloved people in show business, idolized by everyone from Joan Rivers and Louis CK to Chris Rock and Sarah Silverman.

Billy Crystal tweeted simply, “A giant loss.”

“We lost a great one. fast furious brilliant for decades the definition of genius,” Sandra Bernhard said on Twitter.

Some reaction to Rickles’ death matched his style.

“In lieu of flowers, Don Rickles’ family has requested that people drop their pants and fire a rocket,” Patton Oswald tweeted.

James Caan once said that Rickles helped inspire the blustering Sonny Corleone of “The Godfather.” An HBO special was directed by John Landis of “Animal House” fame and included tributes from Clint Eastwood, Sidney Poitier and Robert De Niro.

Carl Reiner would say he knew he had made it in Hollywood when Rickles made fun of him.

Rickles patented a confrontational style that stand-up performers still emulate, but one that kept him on the right side of trouble. He emerged in the late 1950s, a time when comics such as Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl were taking greater risks, becoming more politicized and more introspective.

Rickles managed to shock his audiences without cutting social commentary or truly personal self-criticism. He operated under a code as old the Borscht Belt: Go far — ethnic jokes, sex jokes, ribbing Carson for his many marriages — but make sure everyone knows it’s for fun.

“I think the reason that (my act) caught on and gave me a wonderful career is that I was never mean-spirited,” he once said. “Not that you had to like it, but you had to be under a rock somewhere not to get it.”

Rickles’ many friends returned the wisecracks, whether labeling him a man everyone loved to hate or, as his pal Bob Newhart once joked, as a man annoying to travel with. But the topper came, from all people, the radio host Casey Kasem, who dressed up as Hitler at a Martin roast in Rickles’ honour and told the comedian, “You are the only man I know who has bombed more places than I have.”

In 2008, he won the Emmy for best individual performance in a variety show for the Landis film, “Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Project.” In 2012, he received the Johnny Carson Award for Comedic Excellence, a fitting tribute for a man whose big breakthrough came on “The Tonight Show” more than 40 years earlier.

Rickles was a stage comic and occasional movie actor when he sat down on the couch next to Carson’s desk and muttered, “Hello, dummy.” The studio audience was initially startled, but when the host began laughing uncontrollably, so did everyone else. He would appeared countless more times, haranguing Carson about not being invited more often or mocking his own love life.

“My wife just lays there, saying, ‘Help me with my jewelry,”’ was a typical joke.

For his standup act, Rickles would begin a show by charging on stage and berating the people sitting down front. To an elderly lady he might say, “What are you doing up, Mom? Go lie down.” To a young man: “Look at this kid staring. That comes from locking yourself in the bathroom too much.” After kissing a woman’s hand: “What’d you have for dinner? Fish?”

His bald heading shining, he would gleefully croon his theme song, “I’m a Nice Guy,” and make fun of blacks and gays, the Irish and the Italians, with special attention for his own people, the Jews. A favourite epithet was the nonsensical “hockey puck,” as in, “You’re a real hockey puck.”

He recalled during a 2003 interview that he began using it on hecklers in the 1950s, although he couldn’t recall exactly why. As to why it caught on: “I guess it sounded like swearing,” said Rickles, who never used profanity in his act.

To his great disappointment, Rickles was never able to transfer his success to a long-running weekly situation comedy. “The Don Rickles Show” lasted just one season (1972). “C.P.O. Sharkey,” in which he played an acid-tongued Navy chief petty officer, fared slightly better, airing from 1976 to 1978. The show’s most notable moment was unplanned: Carson barged in the middle of a live taping to complain that Rickles had broken his cigarette box when the comedian had appeared on “The Tonight Show” the night before.

Rickles’ films ranged from comedies to dramas and included “Run Silent, Run Deep” (starring Clark Gable), “The Rat Race,” (Tony Curtis), “Kelly’s Heroes” (Eastwood) and Martin Scorsese’s “Casino” (De Niro). He also appeared in four “Beach Party” films in the 1960s and provided the voice of Mr. Potato Head in the animated “Toy Story” films.

“I did have somewhat of a career. I did some good movies,” he said in 2007. “On the whole, I think that (movies) and Broadway are the two things that I would have liked to have a little more of. But I’m happy with my career.”

Rickles set out to be a serious actor, enrolling in New York’s American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where one of his classmates was Jason Robards. He had little luck finding acting jobs, however, and supported himself by selling used cars, life insurance and cosmetics — badly, he said. (“I couldn’t sell air conditioners on a 98-degree day.”)

He finally decided to try comedy, appearing at small hotels in New York’s Catskill mountains and in rundown night clubs. The turning point came at a strip joint in Washington, D.C.

“The customers were right on top of you, always heckling, and I gave it right back to them,” he recalled in 1982.

The audience laughed and wanted more. In a style sometimes compared to an earlier insult comic, Jack E. Leonard, Rickles continued to hone his act, and, in 1957, his mockery of Sinatra from the stage gave him a boost.

Rickles became the unofficial court jester of Sinatra’s Rat Pack, ridiculing his singing, his love life and his alleged connections to organized crime. In a famous 1966 profile of Sinatra for Esquire magazine, Gay Talese described a Rickles performance in Las Vegas attended by the singer and his entourage.

“His humour is so rude, in such bad taste, that it offends no one — it is too offensive to be offensive. Spotting Eddie Fisher among the audience, Rickles proceeded to ridicule him as a lover, saying it was no wonder that he could not handle Elizabeth Taylor,” Talese wrote.

“Then he focused on Sinatra, not failing to mention (then-girlfriend) Mia Farrow, nor that he was wearing a toupee, nor to say that Sinatra was washed up as a singer, and when Sinatra laughed, everybody laughed.”

Donald Jay Rickles was born in 1926 in New York City’s borough of Queens. According to his mother, he began entertaining family members with his comedy when he was 6. Rickles jokingly called his mother the “Jewish General Patton,” but owed some of his success to her; she was friendly with Sinatra’s mother, who convinced the singer to check out Rickles’ act.

Rickles said he truly fell in love with acting when he appeared in high school plays. He often said that he used insults as a way of shielding his insecurity.

“I loved to perform, but I was really a very shy and frightened kid,” he recalled in 1980.

He married Barbara Sklar, his agent’s secretary, in 1965, and they had two children, actress Mindy Rickles and writer-producer Lawrence Rickles, who helped on the HBO film about his father. Lawrence Rickles died of complications from pneumonia in 2011.

In a 1993 Associated Press interview, Don Rickles’ brassy voice softened when he was asked how he wanted people to remember him.

“If people know me well, they know I’m an honest friend. I’m emotional; I’m caring; I’m loyal. Loyalty in this business is very important.”

Observed De Niro at a Spike TV roast in 2014: “Don is something rare, (a) true friend, a wonderful human being. If he weren’t, he would never be able to get away with being such an a–hole.”

Besides his wife, Rickles’ survivors include their daughter Mindy Mann, her husband Ed, and Rickles’ two grandchildren, Ethan and Harrison Mann. Funeral services will be private. In lieu of flowers, it is suggested that donations be made to the Larry Rickles Endowment Fund at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.