In a new series, our writers explore how food shaped Australian history – and who we are today.

Curry occupies a grey area in Australia: sometimes exotic and other, sometimes ordinary, often a bit of both.

Advertised in Australia as early as 1813, curry powder was a familiar ingredient for British colonists, developed in British India through a process of “negotiation and collaboration”.

Curry powder was a food of empire.

For the British colonialists who moved to Australia, curry powder was an “agent of transformation”. In a new country with unusual animals, these spices could render the unfamiliar into the familiar, as in “Iguana” tail curry and curried wattle bird.

Writing in the Melbourne Herald in 1874, journalist Marcus Clarke said a man who had not eaten curried wombat “has not used his opportunities”.

In his 1893 dietary advice publication The art of living in Australia, physician Philip Muskett proposed vegetable curry as a suitable national dish.

By the early 20th century, curry was a standard feature of Australian cookbooks and recipes. Curry powder was a given pantry item. In most discussions, curry barely rated a second mention: it was known, accepted and widely eaten.

Sugar and spice and all things nice

Keen’s curry powder was first blended in Hobart in the 1860s by British immigrant Joseph Keen. By the 1960s, the company was promising curries “fit for a Maharajah” such as Murgh Korma and Kare Daging.

Trove

But these promises of a “rich true Indian flavour” were undermined by the use of stereotypes to sell their product.

An advertisement from 1965 read:

To the Indian housewife, “curry” means a richly spiced sauce … Indians curry anything.

Keen’s suggested recipes included ingredients such as canned fruit, plum jam, sultanas and tomato sauce alongside the curry powder.

From the 1930s, Australians developed a fashion for sweeter curries — perhaps initially stemming from the need to substitute unavailable souring agents such as tamarind.

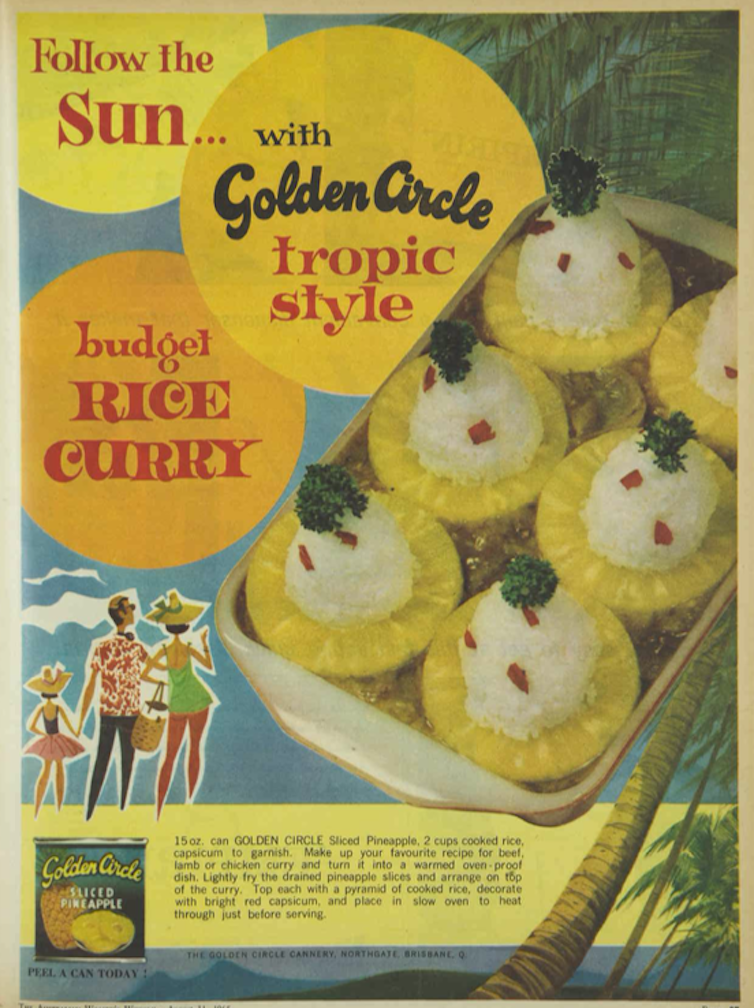

But it also reflected a sweetening Australian palate and successful marketing campaigns by companies such as Golden Circle, who suggested meat curries be topped with their tinned pineapples.

Trove

A recipe for “Australian Curry” published in the 1981 Catholic Women’s League of Tasmania cookbook is characteristic of these tastes, featuring tinned pineapple, a granny smith apple, two bananas, meat, a tin of tomato soup and one dessertspoon of curry powder.

Looking outward

From the 1960s, sweet Australianised curries increasingly competed with a trend of heightened (although often questionable) cultural knowledge in the context of Australia’s broader cultural, economic and political change.

Post the second world war, a booming economy allowed for greater emphasis on lifestyle and travel. Increasingly aware of our proximity to Asia, Australia shifted its gaze to its own neighbourhood. There was a boom in international food in restaurants, on television and in homes.

The Colombo Plan and Vietnam War resulted in greater migration from Asian countries. The White Australia Policy was abolished in 1973, and an international movement for social equality and civil rights movements reverberated through the nation.

Read more:

Colombo Plan: An initiative that brought Australia and Asia closer

Australians integrated foods from the Asia-Pacific region – including the incorporation of dishes from cuisines other than India under the label “curry”, such as Thai green curry.

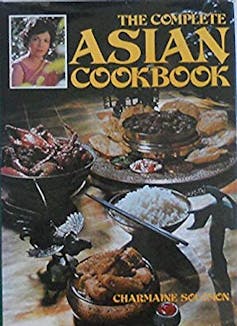

In 1972, Charmaine Solomon published her first book, the South East Asian Cookbook, with recipes for Indonesian rendang daging and Burmese fish kofta curry. Her second, The Complete Asian Cookbook (1976), became one of the most influential cookbooks in Australia.

Solomon’s family heritage from Sri Lanka, Burma and India is reflected in her recipes, moving Australian curries away from sweetened sauces and generic curry powders and towards more nuanced and complex tastes.

In 1980, she pledged to work with Australian tastes, but would not put up with:

those strange and spurious dishes that masquerade under the name of curry and are only the leftover roast disguised in a yellow sauce thickened with flour and flavoured with what some people are pleased to call “curry” [with] bits of apple, banana and sultanas.

Solomon’s history reminds us of how people move — carrying and adapting culinary customs but also contributing to the food cultures of their adopted homes.

From the late 1960s, Australian cookbooks and magazines shifted towards recipes for more subtle and refined curries. “Australianised” curries didn’t disappear, but knowledge of regional and cultural variations gradually increased.

South Asian migrants opened restaurants and takeaways, tending to offer a stable repertoire of North Indian dishes, reflecting both migration patterns and an Anglo-Australian preference for familiar flavours.

An evolving food culture

Our understanding of curry hasn’t stopped evolving. Australians are still encountering and remaking foods from around the world as curry, and new migrants are expanding our cultural understanding and diets.

From Ethiopian Doro Wat to Afghani Lawang, curry is still at once ordinary and exotic.

Food is never just food. What we ingest becomes part of us, and can be a statement of who we are: a marker of identity. It has the capacity to unite or divide.

While food can signal the boundaries of cultures between “us” and “them”, it can also mark the spaces where these delineations break down.

I wonder what sort of curry Muskett might propose as a national dish today?![]()

Frieda Moran, PhD Candidate, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.