Long-term care homes in Canada provide essential round-the-clock care for approximately 425,000 of Canada’s most vulnerable people. Among Canadians aged 85 and older — the fastest growing segment of our population — 32 per cent live in long-term care.

Residents often have multiple complex medical conditions and take numerous medications. Physically frail and cognitively impaired, many residents rely on care staff to get in and out of bed, use the toilet, bathe and eat. Most are very likely to fall.

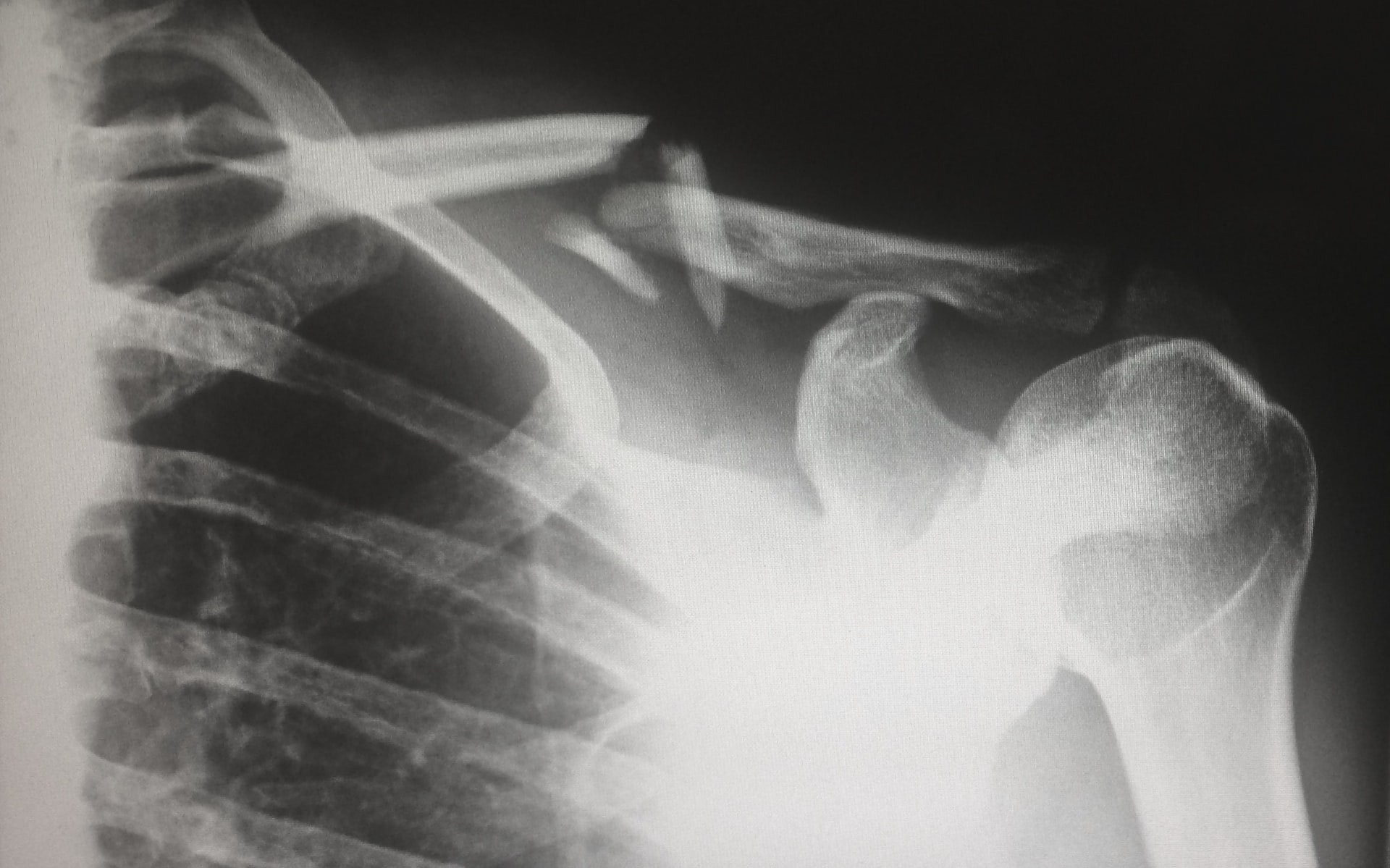

I work with a team of biomedical scientists at Simon Fraser University and the Fraser Health Authority studying falls in long-term care. Over our four-year study, we learned that approximately 70 per cent of residents fall at least once in any given year, and many do so multiple times. Injuries occur in about 50 per cent of these cases, the most serious of which are hip fracture and traumatic brain injury. These rates are cause for concern — they are two to three times higher than we typically observe among older adults who live independently.

High incidence of falls and injuries

A separate study recorded videos of hundreds of real-life falls in dining rooms, hallways and lounges in long-term care homes. In these public settings, falls happen during common, everyday activities such as forward walking, standing and sitting down.

The underlying cause is most often incorrect weight shifting, followed by tripping. What’s particularly shocking is that in close to 40 per cent of events, residents sustain impact to their heads.

Despite decades of effort to design, evaluate and implement interventions to prevent falls in long-term care, we still do not have effective methods for doing so. Strategies that are effective for older adults living independently in the community, namely balance and functional exercises, simply don’t work in long-term care because residents have complex medical histories and multiple risk factors.

In the past, residents were sometimes physically or chemically restrained so they were less likely to fall. But that seriously restricted quality of life. Thankfully long-term care homes today favour progressive policies that honour and respect the dignity and individuality of residents. This includes giving residents the right to choose to move freely, which may mean falling down more often.

Given the persistent challenge of preventing falls in long-term care homes, researchers and health-care organizations are shifting their focus toward the management of falls. A pressing question now is how can we prevent and reduce the severity of injuries when falls do happen?

We’re working on this, but it’s not an easy task. Two main strategies to prevent fall-related injuries are emerging.

Wearable protective gear

Wearable protective gear is designed to reduce impact forces sustained by the body during falls. One example is hip protectors. These are undergarments, shorts or pants with soft pads or hard shields on the sides that absorb some of the impact of a fall to protect the bone.

When worn during a fall, hip protectors substantially reduce the chance of a hip fracture among long-term care residents. Low compliance in wearing hip protectors is an issue, however, and has limited their effectiveness on the population level. Increasing the use of hip protectors in long-term care homes across the country is a major focus of new research.

Given the prominence of serious head injuries during falls, researchers are also exploring the development and effectiveness of protective head gear, like helmets, that are designed to protect against fall-related traumatic brain injury. This is a very new area of research and one where having patients as partners in the creation of these technologies will be key to their acceptance.

Environmental interventions

Modifications to the physical environment at long-term care homes aim to promote safer mobility. Their promise lies, in part, in the ubiquitous nature of protection they could provide — unlike wearable protective gear, the effectiveness of environmental interventions does not rely on active user compliance.

One example is compliant flooring, which provides a softer landing surface than standard flooring to protect against injury. Our four-year randomized study of one type of compliant flooring at a long-term care home did not find any reduction in fall-related injuries, so the search for alternate strategies continues. Newer brands and models of flooring systems may prove more effective.

Canada’s population will age considerably in the coming decades. By 2031, approximately one in four Canadians will be 65 years or older. As such, the number of long-term care residents will likely grow rapidly. The health and well-being of residents demands increased attention, action and innovation from government, policy-makers, health-care organizations, clinicians, industry, researchers and the public. The people who spend their final years in long-term care — our parents and grandparents — deserve it.![]()

Dawn Mackey, Associate Professor in Biomedical Physiology and Kinesiology, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.