Outside China, opinions about China’s performance during the COVID-19 pandemic is divided between praise and blame. But little is known about how Chinese citizens themselves view their government’s response.

I recently received a rapid response grant on the COVID-19 pandemic from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to study public responses and social relations in times of crisis. I have brought together front-line researchers from China, including those at the centre of the outbreak — Wuhan City — as well as political culture and public health scholars in Canada and Sweden.

We are studying how governments within and across countries have been responding to the global pandemic and what might explain the varying responses. We are also considering how people perceive government performance during the crisis and how that, in turn, might affect public trust in government after the pandemic.

In the case of China, some have worried that China’s handling of the crisis since the outbreak may have undermined Chinese citizens’ longstanding support for their government.

Major news media such as the New York Times and Time magazine have reported that the COVID-19 crisis shows China’s governance failure, which could derail President Xi Jinping’s China dream.

But how satisfied are Chinese citizens with their government performance during the crisis? In collaboration with 17 Chinese academics, I conducted a large-scale survey in late April 2020, in the immediate aftermath of the reopening of Wuhan. In total, 613 university students from 53 universities across China joined our team. This served to ensure that the survey was widely distributed across all regions.

Each interviewer reached out to their contacts and ask their permission first before sending them the link that would enable them to fill out the survey. The purpose of this approach was to ensure meaningful engagement with the survey, similar to a face-to-face situation. Respondents were assured their responses would be anonymous.

We obtained data from 19,816 people in 31 provinces or provincial-level administrative regions across China.

Opinion divided

Outside China, opinions of China’s performance are split. On one hand, the Chinese government has been openly criticized for allegedly suppressing vital information about the outbreak in its early stages and downplaying its severity.

U.S. President Donald Trump has repeatedly said the virus could have been contained by China. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, along with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Foreign Minister Marise Payne, have also called for an investigation into how China handled the initial outbreak in Wuhan.

On the other hand, the Chinese government has also been praised for its efforts to contain the virus and the help it offered to other countries as they fought the pandemic. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, head of the World Health Organization, said in a statement:

“The Chinese government is to be congratulated for the extraordinary measures it has taken to contain the outbreak, despite the severe social and economic impact those measures are having on the Chinese people.”

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic praised China, saying it was the only country that helped Serbia fight the outbreak. He even kissed the Chinese flag in a show of gratitude.

Citizen satisfaction high in China

In our survey, we asked Chinese people how satisfied they are with information dissemination during the pandemic from various levels of government including national, provincial, city, county and township or village governments.

We also asked their satisfaction with the delivery of daily necessities and protective equipment, like masks, from each level of government. Responses were originally coded on a 1-5 scale with 1 corresponding to “not at all satisfied,” 2 to “not satisfied,” 3 to “OK,” 4 to “satisfied” and 5 to “very satisfied.”

I created an overall satisfaction index that combines all levels of government on both questions for each individual.

The satisfaction index ranges from 10 (unsatisfied with all levels of government on both questions) to 50 (satisfied with all levels of government on both questions). On this 10-50 scale, Chinese citizens indicated an overall satisfaction score of 39.2 (38.8 in Hubei province, where Wuhan is located). This suggests that Chinese citizens’ satisfaction with government performance during the pandemic is very high.

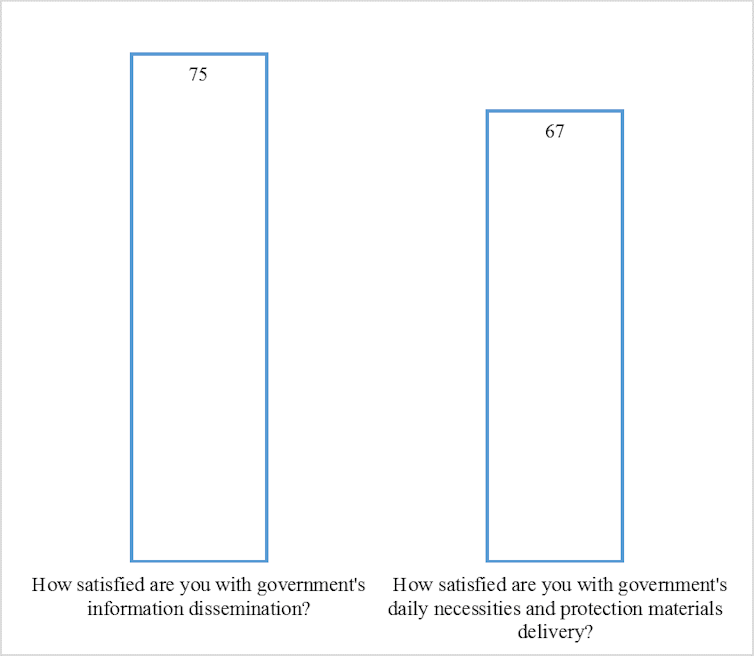

To better present the findings, I recoded each item from the 1-5 scale into a binary measure, designating 4 and 5 as satisfied (1) and other categories as unsatisfied (0). On this binary scale, about 75 per cent of China’s citizens indicated they were satisfied with government’s information dissemination, while 67 per cent were satisfied with the government’s delivery of daily necessities and protection materials during the pandemic. See below:

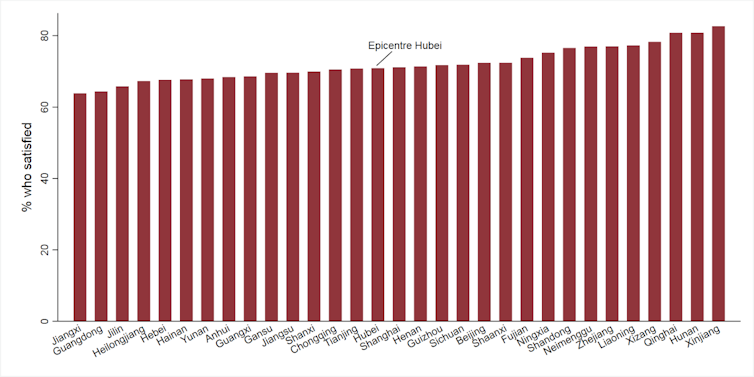

Next, I considered how citizen satisfaction varies across provinces. I have found that in provinces with a small number of confirmed cases such as Xinjiang, Hunan, Qinghai, Tibet and Liaoning, citizens are more satisfied.

However, in Jiangxi, Guangdong, Jilin, Heilongjiang and Hebei, where more people were infected, citizens are less satisfied. This suggests that citizen satisfaction might reflect actual government performance. Still, citizens in Hubei province, the epicentre of the outbreak, were ranked in the middle in terms of their satisfaction.

Critical citizens are less satisfied

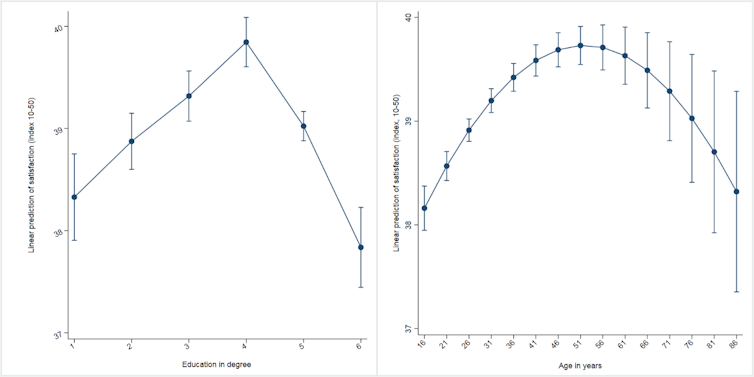

A large body of literature, including my own research, suggests that critical citizens — empirically, usually those who are young and highly educated — are often more critical in their assessment of government performance.

Accordingly, I looked into how education (measured by degree) and age (in years) might predict citizen satisfaction on the 10-50 scale. In my assessment, I also controlled for other demographics, including gender, household income and urban or rural residency.

Both education and age show a non-linear effect on citizen satisfaction. Lower levels of satisfaction were found among those who are highly educated with university degrees and under 30 years old. This suggests that China’s critical citizens were indeed less satisfied with government performance during the pandemic.

Hierarchical citizen satisfaction

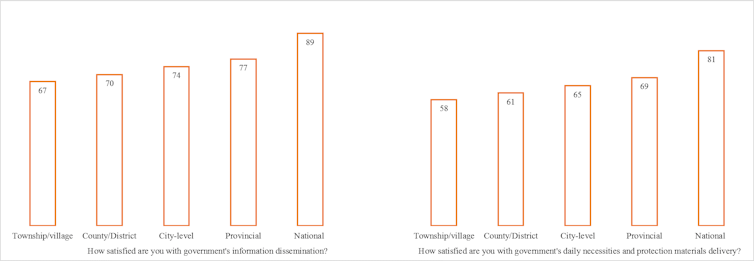

My previous research on political trust has shown that Chinese citizens are often more critical toward the government at the local level when evaluating government performance. In terms of citizen satisfaction, Chinese citizens often express hierarchical citizen satisfaction: they express lower levels of satisfaction for levels of government closer to the people.

Do Chinese citizens continue to hold hierarchical citizen satisfaction in assessing the performance of various levels of government during the COVID-19 crisis?

To find out, I broke down citizen satisfaction according to the level of government.

The results confirm the hierarchical citizen satisfaction pattern. Whereas 89 per cent of Chinese citizens expressed their satisfaction toward the national government on information dissemination during the pandemic, the number fell to 77 per cent for the provincial level government, 74 per cent for the city level, 70 per cent for the county level and 67 per cent for the community or village level of government.

Consistently, in evaluating government deliveries of daily necessities and protective supplies, 81 per cent were satisfied with the national government, but the number fell with each lower level of government. Only 58 per cent were satisfied with their community or village level government, even though this is the level of government that actually delivers essential services during the pandemic.

Taken together, it’s evident that Chinese citizens hold very high levels of satisfaction with the performance of their national government during the pandemic.

When citizens have high levels of satisfaction with how government works, they also become more trusting of government. This suggests that China’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic might have enhanced the legitimacy of its government.![]()

Cary Wu, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.