(Piqsels)

Workers under age 30 have been the first to lose their jobs or be placed on unpaid leave during the COVID-19 pandemic.

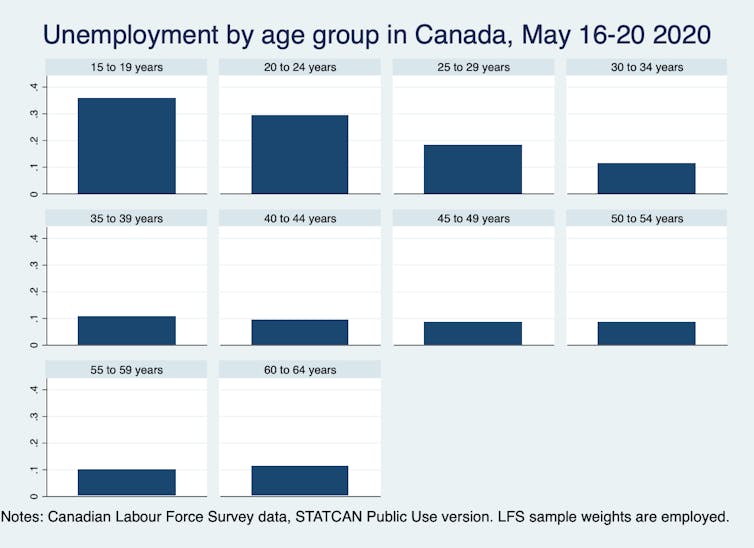

The younger the worker, the higher the unemployment rate in May 2020. The rate was 10 per cent for those aged 31 to 65, but 24 per cent for those under the age of 30.

And among those still employed, the young were nearly twice as likely to be on unpaid leave, according to the May 2020 Labour Force Survey.

Nevertheless, young people possess some labour market advantages.

A large fraction of their skills can be readily transferred to other jobs. Young workers tend not to have small business debts or family obligations. They are unlikely to own homes that must be sold to take up employment in other locations.

Young people also tend to be more physically able to take up seasonal natural resource jobs, which are often lucrative. What’s more, this age group is less likely to have the pre-existing medical conditions that seem to make COVID-19 more deadly.

Spent fewer weeks on the job

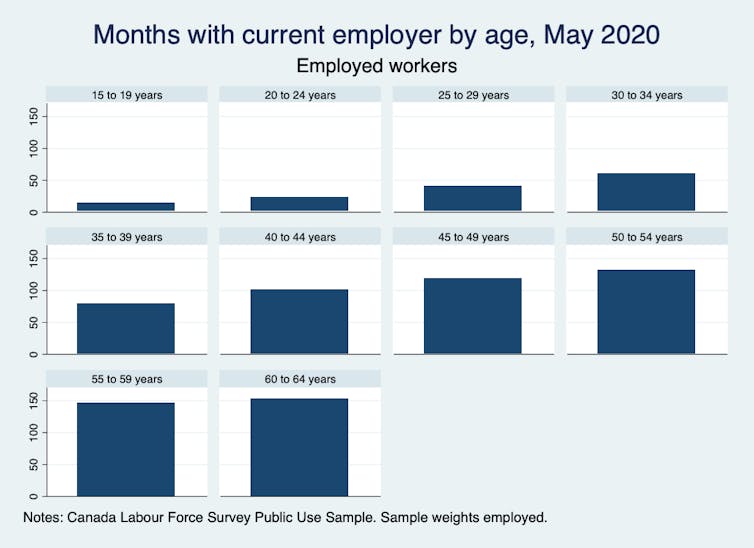

Young workers have generally worked at their jobs for shorter periods than older employees. The Labour Force Survey showed workers under age 30 had been with their current workplace for an average of 31 weeks. Those aged 31 to 65 had worked at the same place for an average of 115 weeks.

Prior to the pandemic, young workers also spent less time unemployed when they did lose jobs.

In April 2019, the average amount of time an unemployed youth had spent without work was about 11 weeks. Unemployed workers aged 30 or older had spent nearly twice as many weeks searching, on average.

Read more:

Employing youth during the coronavirus pandemic is a good investment

Even in a labour market upended by COVID-19, the ways economists think about matching jobs to workers are useful for predicting what might happen to young people’s job prospects.

The amount of time a person spends unemployed is often thought of as an outcome predicted by two variables: the lowest wage a person would be willing to accept and the rate of job offers. When a person receives job offers at a higher rate, and when a person is willing to accept a lower wage, the time spent unemployed will be lower.

New jobs will be created

So how does this help us understand the potential responses young people might have to the current situation?

(Unsplash)

The arrival of the pandemic suddenly destroyed many jobs, but it’s also created some new ones and will continue to do so. These new job vacancies might be very far geographically — and psychologically — from what young people had envisioned themselves doing in the summer of 2020.

The emergency safety nets provided by COVID-19 benefits reduce the financial risk to youth of leaving big cities. Young people might have an unexpected chance to take advantage of access to endless nature and low population density in places where new job opportunities arise.

Money received under CERB or Emergency Student Benefits (CESB) goes a lot further in less densely populated places. This also makes moving out of big cities attractive. A two-bedroom apartment in some small cities can be rented for less than $1,000 per month. A three-bedroom house near Lake Superior in Thunder Bay, Ont., can be rented for the same price.

There are currently fewer job vacancies in the cities and in sectors that have traditionally employed young people during the summer months, such as retail, accommodation and tourism.

Workers needed

Between April and May 2020, 47 per cent of new jobs in Canada were outside of the country’s nine major metropolitan areas. That could be because service jobs that are compatible with physical distancing and people’s holiday plans might not exist in cities this year.

Physical jobs that must take place outside can be done as usual, because physical distancing has always been built in. Yet, as of late May, many seasonal resource-based industries across the country were still advertising for summer workers.

In many cases, industries need to replace their regular workforce of international workers, who will not arrive this year.

The challenge for employers and policy-makers is to get young people to accept job offers when they can receive emergency these benefits without working.

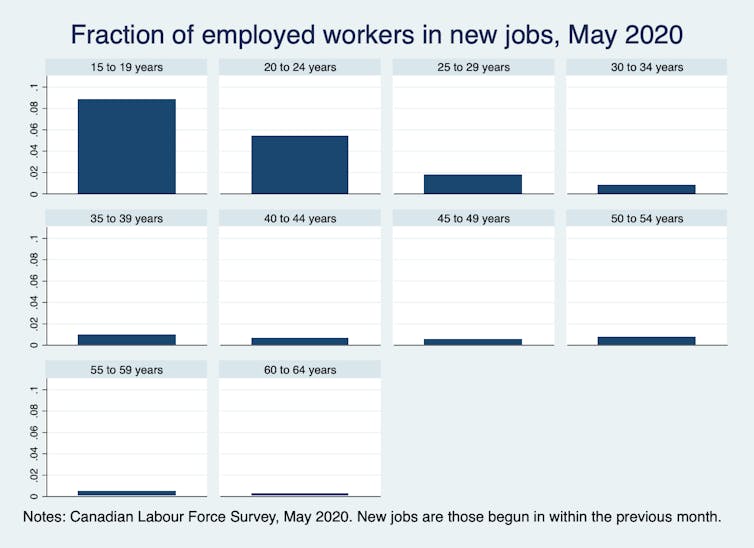

Younger workers do appear to be relatively likely to be in new jobs.

Still, anecdotal evidence suggests that agricultural sector employers have had extra problems hiring university students this year. A post-secondary student can live with parents and collect $1,250 without working, and this is attractive for some.

Grocery stores everywhere must also compete with these emergency benefits when hiring new employees to deliver groceries.

Benefits to moving out of big cities

Yet the benefits of moving out of town for a job may persist for some time. With post-secondary studies going remote in the fall, many young people may be able to reside and work part-time in new locations beyond the summer months.

(Piqsels)

Job skills must be practised to be maintained and improved. For those with the majority of their working lives ahead of them, this is particularly important.

Being flexible about both location and the nature of employment will help youth make the most of the current challenging labour market situation.

The new and different skills learned will be of value in many different job situations encountered in their future working lives. And keeping some connection to the paid workforce will be the best insurance against permanent scarring effects of being young adults during the pandemic.

An important question asked of young workers in future job interviews might be:

“What did you do during the COVID-19 pandemic?”

Hopefully there will be a lot of inspired answers.![]()

Louise Grogan, Professor of Economics, University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.