Lifestyle

Lidia Bastianich reflects on her path from refugee to head of a family food empire

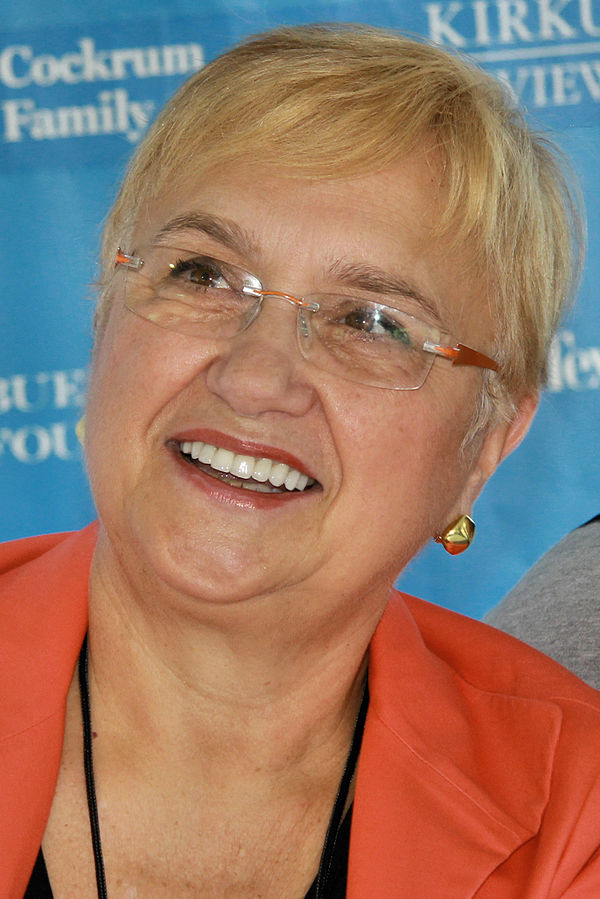

(Photo from Wikipedia)

Lidia Bastianich is America’s Italian grandmother. In a dozen books and on her public television program, Bastianich has schooled American cooks in homemade pasta, the proper use of escarole, and the need to slow down and come to the table.

Not that she’s slowing down, at least not in terms of career. At 68, Bastianich is the matriarch of a restaurant and entertainment empire. Along with her son, Joe Bastianich, and daughter, Tanya Bastianich Manuali, she has partnered on name brand New York restaurants, created product lines of sauces, pastas and cookware, authored bestselling cookbooks and launched a television production company.

And it’s all built on her reputation for home-style Italian cooking, a palate often punctuated by sauerkraut and other ingredients common to the ethnically mixed region of Italy in which she was born.

Bastianich’s new cookbook, “Lidia’s Mastering the Art of Italian Cuisine,” (Alfred A.

Knopf, $37.50) is part recipe guide, part meditation on history and ingredients. We talked with Bastianich about tips and techniques, and about her rise from refugee to food entrepreneur. The conversation was edited for length and clarity.

___

AP: Why this book? And why now?

Lidia Bastianich: This book is the opening of a drawer. I literally put in clippings and ideas—“I want to say this at some point,” “I want to explain to cooks how simple this is.” This drawer had all of this, and I just pulled it out and it evolved into this book. This book is a philosophy of how I cook and how the Italian culture cooks… There are more than 400 recipes. About 40 per cent are the traditional recipes you’ve seen in my books and in other books. Because that’s what the cuisine is. You don’t invent it. It’s a reflection of traditions. The others are my favourite recipes, some of them I adjusted, some I borrowed. I also included Italian-American recipes. How are you going to tell an American that there’s no spaghetti and meatballs in an Italian cookbook? So I explain all of those things.

AP: Did you have an actual drawer stuffed with all this information?

Bastianich: I had some in my mind. But yes, there’s a physical drawer. And a computer folder.

AP: What are the biggest mistakes people make in Italian cooking?

Bastianich: The over-inclusion of ingredients. They feel the more they put into it, the better it gets. It’s the other way. If you focus on great ingredients you let nature show off.

AP: What is the signature of your Italian cooking? What defines it, makes it different from others?

Bastianich: It’s a nurturing, motherly, grandmother approach to cooking. My food is really basic. It’s home cooking Italian food for the family, and it can be done by a home cook. Sometimes chefs, to affirm themselves, need to make something hard. That’s not my message. My message is “You can do it.”

AP: You and your then-husband Felice Bastianich started in 1971 with one restaurant in Queens. You’ve grown that initial business into an empire of big name restaurants—Del Posto, Esca, Eataly with Mario BatalI—food products, cookware, a winery, cookbooks, an entertainment production company. And you’ve done it all with your family, in particular with your son Joseph and your daughter Tanya. Why was it important to make this a family affair?

Bastianich: My kids grew up in that setting, of making food our business.

But I always told them, “You do not want to do this job. We’re in America. You get educated, you get a real American job.” But somehow, they came back. My son came back because he wasn’t happy on Wall Street and he felt he could multiply this philosophy of food. My daughter was a professor in Italy. She was itching for something. She began to help me research the books. I would never have expanded so much had it not been for my children. They came back and they found their passion doing what I was doing.

AP: Yours is a great American story. Many families come to the United States and open a restaurant or a grocery that stays in the family for generations. You opened a single restaurant in Queens. What was the most important factor in growing the business?

Bastianich: I came at a great age. I was 12. I went to high school and college here. I got a lot of the American way of thinking. But at the same time, I was born Italian. I have two of the greatest cultures on earth behind my back. How can you not succeed? I have all the beauty and flavours of Italy, and the marketing savvy, everything that is American. It was this combination of my two countries, communicating my birth country and my adopted country. There’s no place like America if you roll up your sleeves.

AP: You were born in 1947 in a region of Italy that became part of Yugoslavia. What many people don’t know is that your family fled the communist regime there and spent time in a refugee camp before coming to the United States. How did that experience affect you?

Bastianich: We stayed (in the camp) for 2 years. Finally in 1958, Dwight Eisenhower opened up immigration for people fleeing communism and we were one of the first families. Even during communism in Yugoslavia, food wasn’t all that abundant. (In the camp,) breakfast, lunch, dinner, you literally got on line and waited for food. All I can remember is that for lunch almost every day was spaghetti, tomato sauce, an apple and a piece of cheese wrapped in foil. Those little cheeses—you know the ones-

AP: The Laughing Cow?

Bastianich: Exactly. Being on line, waiting, at the mercy of someone giving you food. You were grateful, but I think it instilled in me this real respect for food, and what it is to have food, and not to have food. We had these big communal tables. And the people that were there—we were from Istria, but there were people from Hungary, from Europe—and all different people and languages. You learned at that small age something that has remained in me, about other people and their needs.

AP: In 1981, you decided to move out of your Queens locations, buy a brownstone and open a restaurant in Manhattan, which became the acclaimed Felidia. It was a huge risk. Why did you take it?

Bastianich: This is how you grow. The opportunity was there. You assess the opportunity and if you think you can make it happen you do it. These restaurants in Queens, I made polenta and gnocchi with venison and had developed a following from the city, and from the press, and everyone said, “You guys belong in the city.” And you listen. And it made economical sense. We could leverage the lease (in Queens) to get ourselves settled in Manhattan. It was just a bit over our head and we almost didn’t make it. But once we opened, right away people came and filled the seats. We got three stars from (New York Times restaurant critic) Mimi Sheraton and whoever else along the line. Then that eased off the financial pressure.

AP: You’ve won a James Beard award, the Emmy Award. You cooked for Pope Benedict. What is your most memorable experience or the one of which you’re most proud?

Bastianich: I’m ever so proud of my family. I’m still grateful of how my children decided to come back and make their life what I started.

___

MARINATED WINTER SQUASH

Start to finish: 45 minutes, plus marinating

Servings: 6

1 cup cider vinegar or white vinegar

1 tablespoon sugar

Kosher salt

6 cloves garlic, thinly sliced

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

1 medium butternut squash (about 2 pounds)

1 cup vegetable oil, or as needed

20 fresh basil leaves

In a small saucepan over high heat, mix together the vinegar, sugar and 1/4 teaspoon of salt. Simmer until the sauce is reduced by half. Remove from the heat, drop in the garlic slices, then set aside to cool. Stir in the olive oil.

Slice the squash in half lengthwise and scrape out the seeds. Peel the halves, then place them cut side down on the cutting board and cut crosswise into 1/3-inch-thick half-rounds.

In a large, nonstick skillet over medium-high, pour a thin layer of vegetable oil. When the oil sizzles on contact with the squash, fill the pan with a layer of squash slices, spaced slightly apart. Fry for about 3 minutes on the first side, then flip the slices over. Fry on the second side another 2 or 3 minutes, or until the slices are cooked through (easy to pierce with a fork), crisped on the surface, and caramelized on the edges. Lift out the slices with a slotted spoon, draining off the oil, and lay them on paper towels. Sprinkle salt lightly on the hot slices. Working in batches, cook the remaining squash the same way.

Arrange a single layer of fried squash in the bottom of a shallow serving dish large enough to hold all of the squash. Scatter four or five basil leaves on top. Stir up the marinade, then drizzle a couple spoons of it over the squash. Scatter some of the garlic slices on the squash, too. Layer all the squash in the dish this way, topping each layer with basil leaves, marinade and garlic. All the seasonings should be used; drizzle any remaining marinade over the top layer of squash.

Cover the dish in plastic wrap and refrigerate the squash to marinate for at least 3 hours, or preferably overnight. Let the squash return to room temperature before serving.

Nutrition information per serving: 180 calories; 100 calories from fat (56 per cent of total calories); 11 g fat (1 g saturated; 0 g trans fats); 0 mg cholesterol; 170 mg sodium; 18 g carbohydrate; 3 g fiber; 4 g sugar; 2 g protein.

(Recipe adapted from Lidia Bastianch’s “Lidia’s Mastering the Art of Italian Cuisine,” Knopf, 2015)