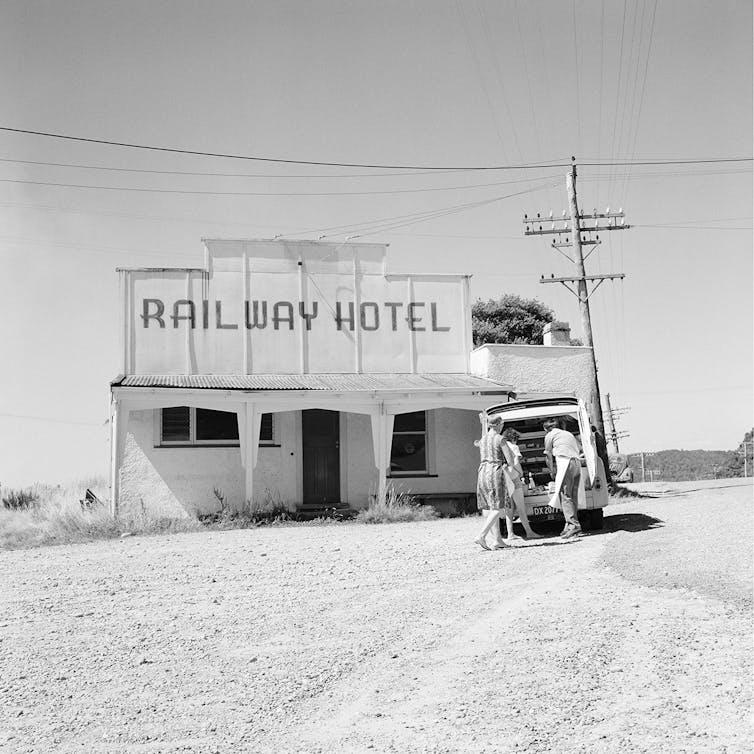

National Library ref AWM-0705-F

They try but invariably fail – those writers who believe they are capable of encapsulating in prose or verse the essence of what it means to be a New Zealander. Even at the point of publication, their works seem anachronistic and clichéd.

Harnessing the New Zealand identity has proven to be as challenging as clutching at fog – it may be apparent everywhere, but it seems impossible to pin down.

But if you do want a representation of New Zealandness over the past six decades, the work of the photographer Ans Westra (1936–2023) is in many ways unsurpassable.

Westra produced what amounts to a national photo album, in which a vast span of the country’s everyday existence was documented with unrivalled skill and perception. At their best, her images crossed that threshold into a liminal space where culture, memory, history and experience all fused together.

Born in Leiden in the Netherlands in 1936, Westra arrived in New Zealand in December 1957. She went on to become unquestionably one of New Zealand’s greatest documentary photographers. Practically every image she produced was a masterpiece of composition, lighting, space, form, angle and subject choice.

She was also able to achieve a sort of artistic alchemy in these works – taking the base elements of film, camera, card and chemicals, and converting them into an entrancing amalgam of scenes that reflected the essence of the nation’s intricately-marbled identity.

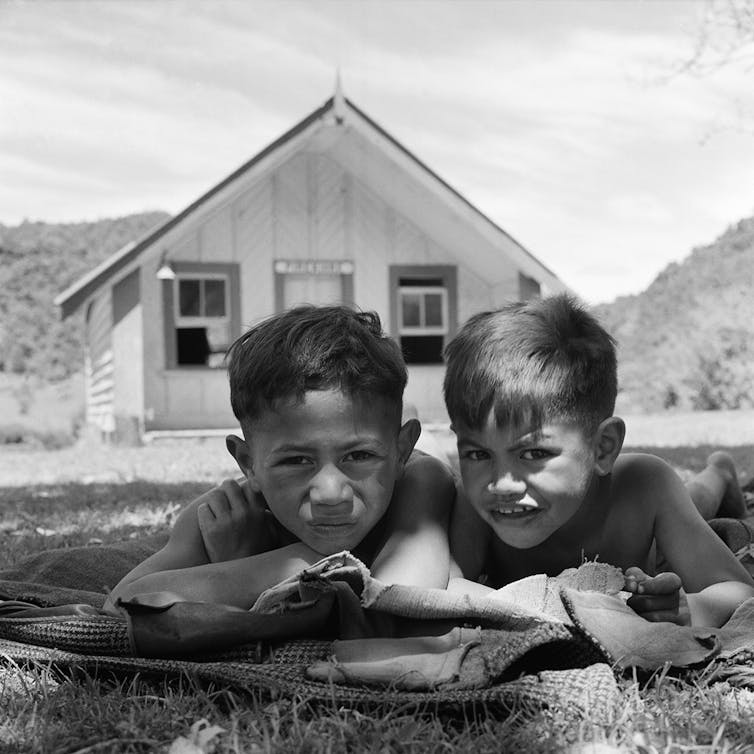

National Library, ref AW-0265

Elevated ordinariness

In her works, the boundaries between documentary photography and art photography were completely porous, which enabled her to conjure up New Zealandness in an artistic as well as descriptive form.

Of course, subject selection was vital. But instead of chasing the sensational or the sublime, Westra chose to fossick around the everyday and the mundane – a realm where her skills were unequalled. After all, who else could infuse such luminosity into scenes that at first glance appeared plain and even dreary?

She seemed consumed by the urge to document every crevice of our day-to-day lives, but in ways that often elevated ordinariness into profound poignancy. Her approach shunned artifice and visual gimmickry in favour of penetrating cultural and social exploration, leaving her photographs to simmer rather than fizz.

The photograph titled “Māori on Willis Street” exemplifies this approach. The image was one of thousands she took documenting aspects of post-war Māori urbanisation.

National Library, ref AWM-0125-2-F

The picture is of a young person staring blankly out into a Wellington street on a rainy day. But instead of a photograph of the entire subject in profile, Westra positioned her shot in a way that made the back of the subject’s head and shoulders visible though a shop’s corner display window.

This had the effect of obscuring partly the clarity of the outline of the subject, while simultaneously projecting reflections of the traffic and buildings on the foregrounded window.

This virtuoso composition does not allow the viewer simply to glance before turning the page. Instead, the image demands contemplation. The material world is shown up here for the surface-only value it possesses, along with its capacity to distract and elude.

The bright lights of the urban Promised Land have been exposed as just a superficial glare. The photograph’s foreground is dominated by this dark-coated youth who appears almost as a silhouetted figure. The background is an indifferent, even life-depleting cityscape.

Bleak shop facades line this commercial canyon, offering the subject no joy or optimism – just an awning to shelter from the drizzle. Above all, though, the viewer is drawn to the solemn stillness of the subject’s face, which conveys a sense of overpowering loneliness and mournful gloom.

National Library, ref AWM-0264-F

An exposition of self

In the early 1990s, during a period of acute self-reflection, Westra jotted down some revelatory notes about her approach to photography:

The image is the ultimate goal […] subject is only a means to an end […] certainly the photograph is not about the subject.

Photography could not be

solely controlled by the brain. Your personality, subconscious, flows through […] you have to allow it to come through […] for the outcome to be relevant.

Ultimately, she said, photography was “always an exposition of self”. This quasi-biographical exposition was necessarily very public, though. The National Library’s commitment to digitising Westra’s photographs is a fitting gesture of democratising the artistic corpus of this most democratic of photographers.

The result is a collection of prodigious proportions (over 300,000 images will eventually comprise the collection), immense span (over six decades) and ambitious scope.

Even for those New Zealanders born more recently, Westra’s images can serve as a form of prosthetic memory – one that may not be based on direct experience, but that nonetheless props up their collective perceptions of the country.

Days before her death, I asked Westra what specifically it was about her photographs that reflected the character of the country and its people so intimately. Slouched in her armchair, her mind seemed to see-saw between thoughts for a while before she responded in her brittle voice, “Maybe it’s because I’m an outsider”.

This was a crucial observation. She was able to see aspects of New Zealand most of its residents probably took for granted. However, looking at her vast body of work, it is equally true in every sense that Westra was the greatest insider we have ever had.

Ans Westra: a life in photography – Paul Moon (Massey University Press), available May 9.![]()

Paul Moon, Professor of History, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.