Ukraine Female Soldiers

Ukraine is now experiencing a level of existential threat comparable only to the situation immediately after the full-scale Russian invasion in February 2022. But in contrast to then, improvements are unlikely – at least not soon.

Not only have conditions along the frontline significantly worsened, according to the Ukrainian commander-in-chief, Oleksandr Syrsky, but the very possibility of a Ukrainian defeat is now discussed in public by people like the former commander of the UK’s Joint Forces Command, General Sir Richard Barrons.

Barrons told the BBC on April 13 that Ukraine could lose the war in 2024 “because Ukraine may come to feel it can’t win … And when it gets to that point, why will people want to fight and die any longer, just to defend the indefensible?”

This may be his way of trying to push the west to provide more military aid to Ukraine faster. Yet the fact that the Nato secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg, publicly accepts that to end the war Ukraine will have to negotiate with Russia and decide “what kind of compromises they’re willing to do” is a clear indication that things are not going well for Ukraine.

There are several reasons for what appears to be an increasingly defeatist narrative. First is the worsening situation at the front where Ukraine lacks both manpower and equipment and ammunition to hold the line against Russia. This will not change any time soon. The new Ukrainian mobilisation law has only just been approved. It will take time to train, deploy and integrate new troops at the front.

At the same time, Russia’s economy has been resilient to western sanctions and seen growth driven by the war. On top of deliveries from Iran and North Korea dual-use technology, including electrical components and machine tools for arms manufacture, has been supplied by China.

Moscow has also managed to produce a lot of its own equipment and ammunition. Much of this is being made in facilities beyond the reach of Ukrainian weapons.

This is not to say that all is well with Russian resupplies, but they are superior to what Ukraine can manage on its own in the absence of western support.

Bleak outlook

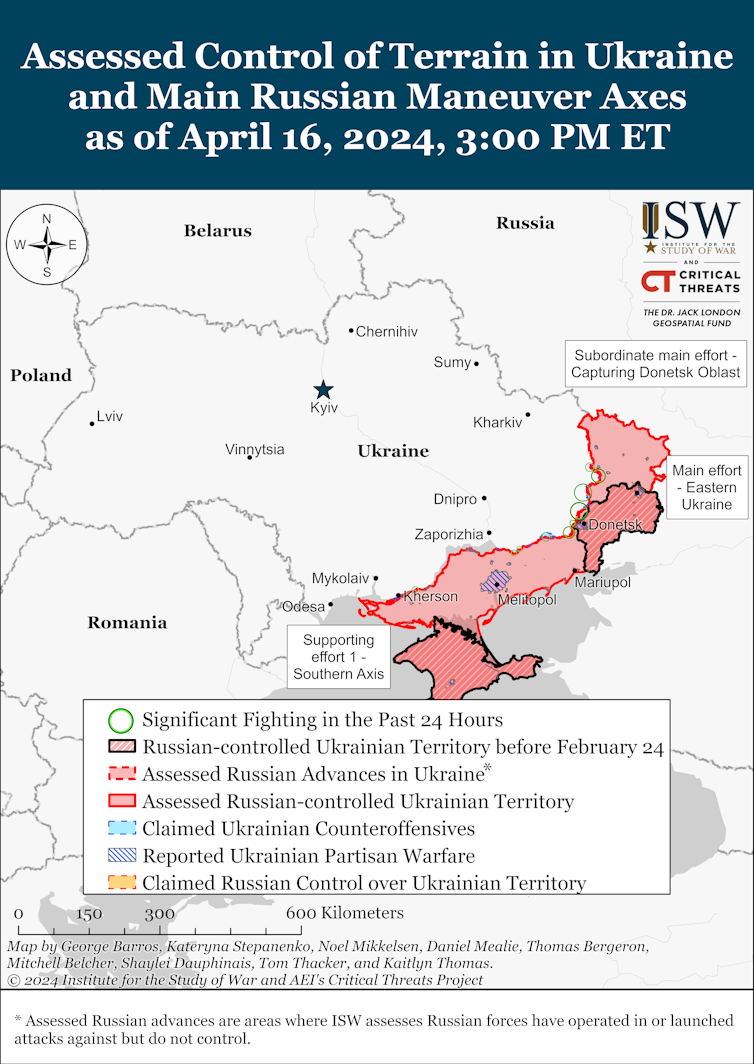

This changing balance of capabilities to sustain the war effort, which now increasingly favours Russia, has enabled the Kremlin to adopt a strategy of grinding down Ukrainian defences along long stretches of the front, especially in Donbas in the east, where Russian pressure has been applied in recent months.

Institute for the Study of War

There is also a large concentration of Russian troops across the border from Kharkiv at the moment. Ukraine’s second-largest city has come under increased Russian attacks over the past several weeks which has led to mandatory evacuations from three districts in the region.

The approximately 100,000 to 120,000 Russian troops would not be sufficient for another successful Russian cross-border offensive, but they are enough to tie down large numbers of Ukrainian forces which, therefore, cannot be used in other potentially more vulnerable areas of the frontline.

Short of a sudden collapse of a significant part of the Ukrainian defence lines, a massive Russian advance is unlikely in the foreseeable future. But part of what Russia is trying to do right now with its broad push against Ukraine’s defences is probe for weaknesses to exploit in a larger offensive later in the spring or early in the summer.

In this context, it is important to remember Russia’s proclaimed overall goals, especially the Kremlin’s territorial claims to all four of the regions Moscow annexed in September 2022. There is no indication that these objectives have changed, and Russia’s current operations on the battlefield are consistent with this.

Capturing the remainder of the Donetsk region would be the first step and provide a basis for subsequent further gains in the Zaporizhzhia region in southern Ukraine and the Kherson region in the centre, especially retaking the city of Kherson, which Ukraine liberated in late autumn 2022.

A Ukrainian withdrawal behind better defensible positions away from the current frontline in Donbas would make the former goal – capturing all of Donbas – more achievable for Russia, but deny the Kremlin success in Zaporzhiya and Kherson. It would also frustrate any Russian hopes of capturing the remainder of the Ukrainian Black Sea coast all the way through to Odesa. Whether this Ukrainian strategy can succeed, however, will significantly depend on what kind of western support will be forthcoming and how soon.

Help wanted – right now

The most optimistic outcome is that Kyiv’s western allies rapidly increase military support for Ukraine. This must include ammunition, air defence systems, armoured vehicles and drones. At the same time, the western defence industrial base, especially in Europe, needs to switch to a similar war footing as in Russia.

On that basis, the situation along the frontlines could stabilise and whatever offensive moves Russia has planned now would not gain much new ground. This most optimistic outcome would constitute a slightly improved situation for Ukraine – any more than that is unlikely at present.

The worst case would be a collapse of parts of the frontline that would enable further Russian gains. While not necessarily likely as things stand right now, if it were to happen it would also be a major problem for morale in Ukraine.

It would empower doubters in the west to push Ukraine into negotiations at a time when it would be weak, even if almost three-quarters of Ukrainians are open to the idea of negotiations. The worst outcome therefore is not Moscow taking Kyiv, but a military defeat of Ukraine in all but name.

A major Russian offensive in the summer, if successful, would force Kyiv into a bad compromise. Beyond defeat for Ukraine, it would also mean humiliation of the west and a likely complete fracturing of the so far relatively united front of support for Kyiv, thus further empowering the Kremlin. In such a scenario, any compromises imposed by Russia on Ukraine on the back of Kremlin wins on the battlefield would probably be mere stepping stones in Putin’s unending quest to restore the Russian empire of his Soviet dreams.![]()

Stefan Wolff, Professor of International Security, University of Birmingham and Tetyana Malyarenko, Professor of International Relations, Jean Monnet Professor of European Security, National University Odesa Law Academy

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.