Business and Economy

Inflation: raising interest rates was never the right medicine – here’s why central bankers did it anyway

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey (Photo: Bank of England/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Inflation remains too high in the UK. The annual rate of consumer price inflation to September was 6.7%, the same as a month earlier. This is well below the 11.1% peak reached in October 2022, but the failure of inflation to keep falling indicates it is proving far more stubborn than anticipated.

This may prompt the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to raise the benchmark interest rate yet again when it meets in November, but in my view this would not be entirely justified.

In reality, the rate hikes that began two years ago have not been very helpful in tackling inflation, at least not directly. So what’s the problem and is there a better alternative?

Right policy, wrong inflation

Raising interest rates is the MPC’s main tool for trying to get inflation back to its target rate of 2%. The idea is that this makes it more expensive to borrow money, which should reduce consumer demand for goods and services.

The trouble is that the type of inflation recently witnessed in the UK seems less a problem of excessive demand than because costs have been rising for manufacturers and service providers. It’s known as “cost-push inflation” as opposed to “demand-pull inflation”.

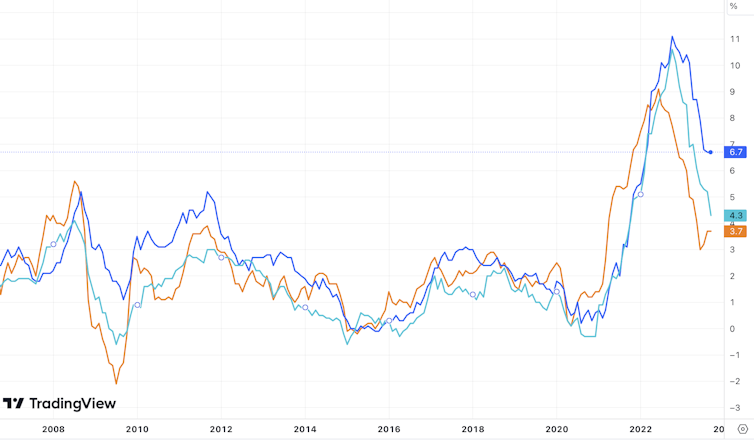

Inflation rates (UK, US, eurozone)

Trading View

Production costs have risen for several reasons. During the COVID-19 pandemic, central banks “created money” through quantitative easing to enable their governments to run large spending deficits to pay for furloughs and other interventions to help citizens through the crisis.

When countries started reopening, it meant people had money in their pockets to buy more goods and services. Yet with China still in lockdown, global supply chains could not keep pace with the resurgent demand so prices went up – most notably oil.

Oil price (Brent crude, US$)

Then came the Ukraine war, which further drove up prices of fundamental commodities, such as energy. This made inflation much worse than it would otherwise have been. You can see this reflected in consumer price inflation (CPI): it was just 0.6% in the year to June 2020, then rose to 2.5% in the year to June 2021, reflecting the supply constraints at the end of lockdown. By June 2022, four months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, CPI was 9.4%.

The policy problem

This begs the question, why has the Bank of England (BoE) been raising rates if it’s unlikely to be effective? One answer is that other central banks have been raising rates. If the BoE doesn’t mirror rate rises in the US and eurozone, investors in the UK may move their money to these other areas because they’ll get better returns on bonds. This would see the pound depreciating against the US dollar and euro, in turn increasing import prices and aggravating inflation.

Part of the problem has been that the US has arguably faced more of the sort of demand-led inflation against which interest rates are effective. For one thing, the US has been less at the mercy of rising energy prices because it is energy self-sufficient. It also didn’t lock down as uniformly as other major economies during the pandemic, so had a little more space to grow.

At the same time, the US has been more effective at bringing down inflation than the UK, which again suggests it was fighting demand-driven price rises. In other words, the UK and other countries may to some extent have been forced to follow suit with raising interest rates to protect their currencies, not to fight inflation.

What next

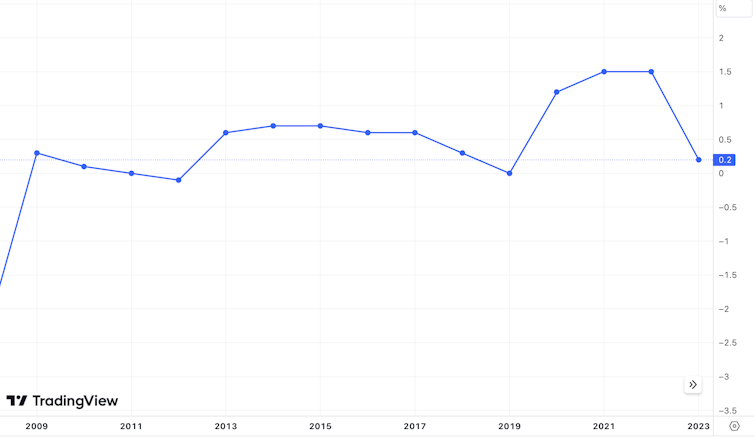

How harmful have the rate rises been in the UK? They have not brought about a recession yet, but growth remains very weak. Lots of people are struggling with the cost of living, as well as rent or mortgage costs. Several million people are due to be hit by much higher mortgage rates as their fixed-rate deals end between now and the end of 2024.

UK GDP growth (%)

If hiking interest rates is not really helping to curb inflation, it makes sense to start moving in the opposite direction before the economic situation gets any worse. To avoid any damage to the pound, the answer is for the leading central banks to coordinate their policies so that they cut rates in lockstep.

Unless and until this happens, there would seem to be no quick fix available. One piece of good news is that the energy price cap for typical domestic consumption was reduced from October 1 from £1,976 to £1,834 a year. That 7% reduction should lead to consumer price inflation coming down significantly towards the end of 2023.

More generally, the Bank of England may simply have to hope that world events move inflation in the desired direction. A key question is going to be whether the wars in Ukraine and Israel/Gaza result in further cost pressures.

Unfortunately there is a precedent for a Middle East conflict leading to a global economic crisis: following the joint assault on Israel by Syria and Egypt in 1973, Israel’s retaliation prompted petroleum cartel OPEC to impose an oil embargo. This led to an almost fourfold increase in the price of crude oil.

Since oil was fundamental to the costs of production, inflation in the UK rose to over 16% in 1974. There followed high unemployment, resulting in an unwelcome combination that economists referred to as stagflation.

These days, global production is in fact less reliant on oil as renewables have become a growing part of the energy mix. Nonetheless, an oil price hike would still drive inflation higher and weaken economic growth. So if the Middle East crisis does spiral, we may be stuck with stubborn, untreatable inflation for even longer.![]()

Robert Gausden, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.