Canada News

Women in politics: To run or not to run?

Research on women in politics has identified multiple obstacles that hinder women’s representation, with three factors emerging as the most prominent explanations. (Pexels Photo)

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series that includes live interviews with Canada’s top social sciences and humanities academics. Click here to register for In Conversation With Semra Sevi, March 15 at 1 p.m. ET. This is a virtual event co-hosted by The Conversation Canada and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

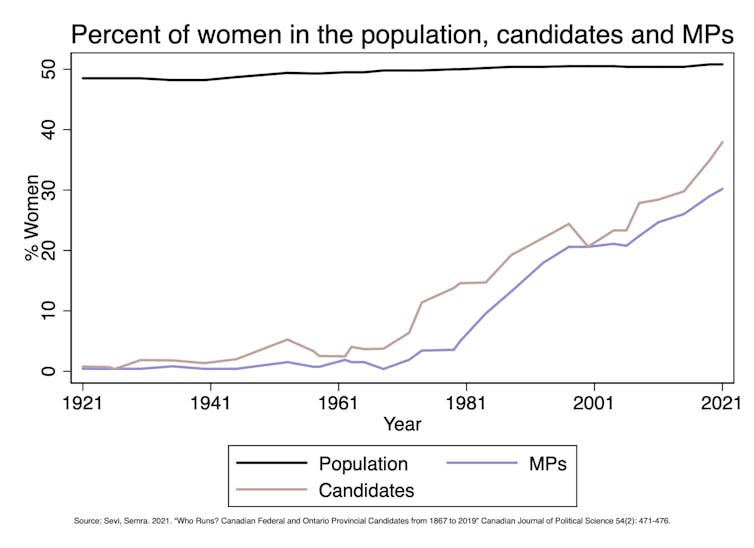

Despite progress towards gender equality, women’s representation in Canadian politics continues to fall short. With only 30 per cent of seats in the House of Commons held by women, there is still a long way to go for Parliament to capture the diversity of the population it represents.

There are several factors that contribute to the persistent gender disparities in the political process. Research on women in politics has identified multiple obstacles that hinder women’s representation, with three factors emerging as the most prominent explanations.

Three obstacles to women in politics

The first is that voters might have gender bias. This is the idea that, for various reasons, voters might prefer a man over a woman candidate.

The second is that women may not be interested to run as candidates. This is the idea that women might be more risk-averse when it comes to campaigns and elections, or that women may lack self-confidence and have lower levels of political ambition compared to men.

The third obstacle is that even when women are willing to run, parties tend to choose men over women. This might be because they believe the likelihood of men winning is higher than for women. That means that while parties have the tools to diversify candidate slates and to address electoral underrepresentation, they frequently act as gatekeepers.

Semra Sevi, Author provided

Testing the theories with data

I have spent several years gathering data and conducting experiments to examine these theories explaining why women are underrepresented in politics.

I built an original longitudinal dataset that tracks all candidates across elections since 1867 in Canadian federal elections. This is the first publicly available comprehensive data of candidate election returns in Canada.

These data include all candidates who ran for elections at the federal level and includes socio-demographic information about them such as their gender, age, whether they’re incumbents, occupation, Indigenous origins, if they identify as a member of the LGBTQ2+ community and so on. I have also collected similar information for candidates at the Ontario provincial level.

I have used these data to examine whether women get fewer votes than men at both the federal and Ontario provincial level.

I find that while women used to receive fewer votes, this is no longer the case. Women who run are just as likely to win as their men counterparts.

However, if we believe voters are biased against women, we would expect to see this even after they are elected. Therefore, I also examined whether incumbency advantage is gendered. Here also I did not find any evidence to suggest that voters are biased against women incumbents.

More recently, I revisited the second explanation that women are more risk-averse to campaigns and elections with my PhD adviser, André Blais. We designed an online laboratory experiment during the peak of the pandemic. This was an interactive experiment with three elections: 1) a lottery election with no campaign; 2) election with votes but no campaign; and 3) election with votes and a campaign.

We find that women are just as likely as men to be candidates in all three types of elections. In other words, women do not appear to be less willing to run in elections with campaigns.

Political party recruitment

In summary, my work suggests that the underrepresentation of women in politics is not due to a shortage of qualified women candidates or voter bias against women candidates. By process of elimination, my future work will examine whether the gender gap persists because parties tend to prefer men candidates over women candidates.

We see some evidence of this when we look at memoirs written by politicians.

Anecdotally, we know that women are less likely to be encouraged to run for office than men. Memoirs written by men politicians in Canada show a consistent pattern. They reveal that although they believe they were born to lead someday, and were looking to fulfil a lifelong dream, they were more likely to be recruited by multiple sources to run for office.

Women, on the other hand, are more likely to say they entered politics because of a specific policy concern and, if they were recruited, it was by fewer sources and on fewer occasions.

Unlocking the bottleneck for women in politics requires a closer examination of the party recruitment process. By identifying the obstacles that women face, we can pave the way forward towards a more inclusive Parliament.![]()

Semra Sevi, Banting Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Political Science, Columbia University. Incoming Assistant Professor of Canadian Politics, Department of Political Science, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.