Canada News

Early details of N.S. mass shooting not ‘consistent’ with reality: senior Mountie

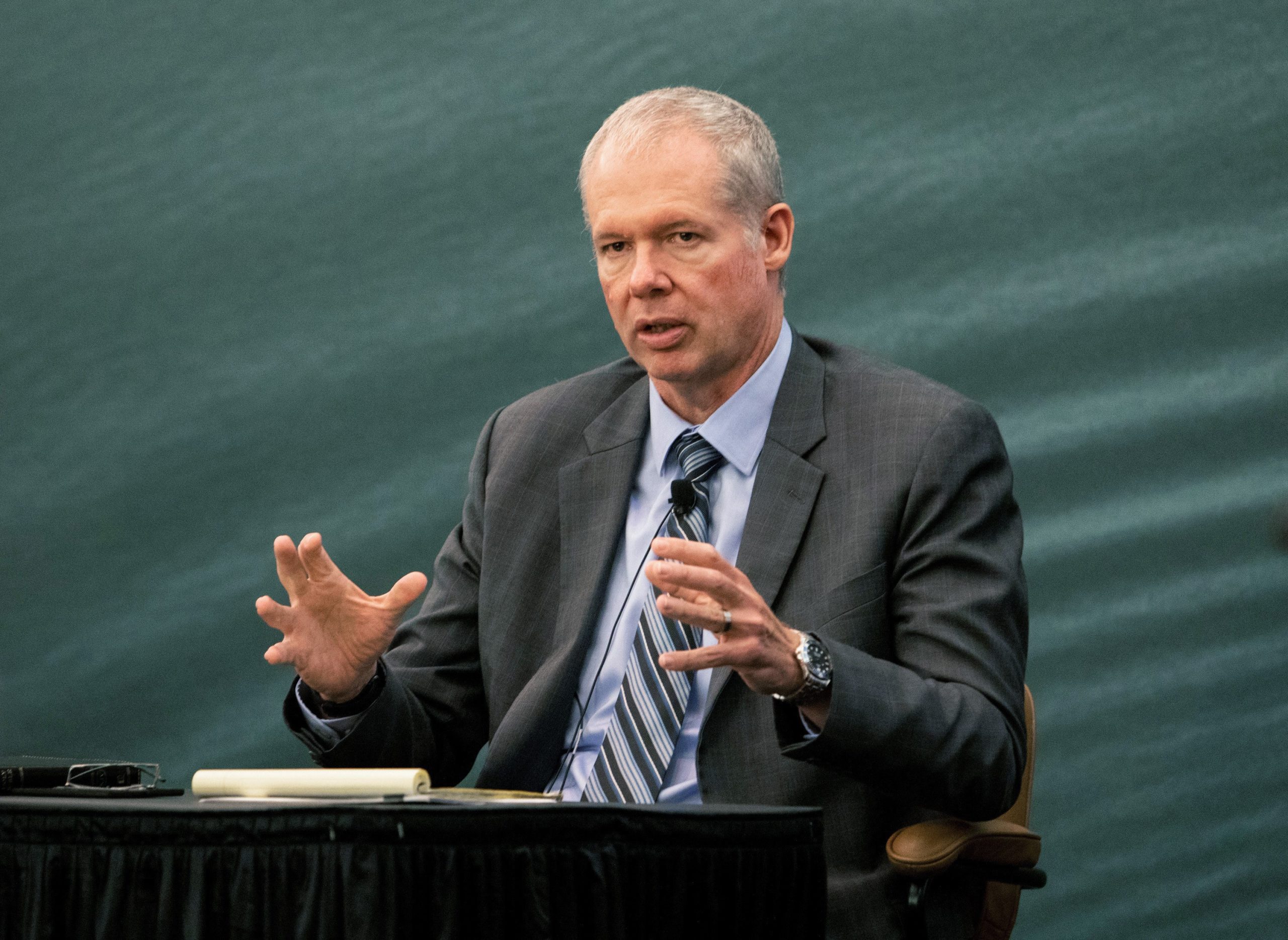

RCMP Chief Supt. Chris Leather is questioned by lawyer Rachel Young at the Mass Casualty Commission inquiry into the mass murders in rural Nova Scotia on April 18/19, 2020, in Halifax on Wednesday July 27, 2022. Gabriel Wortman, dressed as an RCMP officer and driving a replica police cruiser, murdered 22 people. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Kelly Clark

HALIFAX — The Mountie who was among the first to inform the public about the 2020 mass shooting in Nova Scotia testified Wednesday that some of the early descriptions police provided were not “consistent” with the reality of what had happened.

Chief Supt. Chris Leather is the second senior officer to provide evidence before the Mass Casualty Commission — the public inquiry into the April 18-19, 2020, murders of 22 people by a gunman who drove a replica RCMP patrol car.

Commission lawyer Rachel Young asked Leather about language he used with reporters and in news releases, including his comment during the first news conference about the shootings, on April 19, 2020, that the RCMP had responded to a “firearms call” the night before.

“Firearms complaint” was the innocuous term used by an RCMP communications officer in the first tweet about the rampage, at 11:32 p.m. on April 18, even though at that time the Mounties were aware an active shooter had murdered multiple people in Portapique, N.S.

Three days later, Leather told a news conference he was “very satisfied” with that first tweet sent by the RCMP. He also said, “the communications that were being provided were the best and clearest information that could be provided.”

However, in his testimony Wednesday, Leather agreed with Young that the term “firearms complaint” mischaracterized the reality and didn’t conform with RCMP policies requiring police to provide the public with accurate information.

“I think the way it was described … is not consistent with what we were dealing with,” he said.

Leather’s job as criminal operations officer, which he has held since November 2019, includes the supervision of RCMP policing operations in Nova Scotia.

He was the main spokesperson at the first news conference to occur during the mass shooting, on the evening of April 19, 2020, when he answered a question from The Canadian Press about how many people had died. He responded, “in excess of 10,” and declined to clarify.

Later that night, Commissioner Brenda Lucki clarified that at least 17 people were known to have died, adding that the number was expected to rise as the investigation unfolded.

Leather told Young his “now infamous” wording was made with the intention of not exaggerating the death total.

“The problem was it fluctuated depending on who was providing the information,” he told the inquiry Wednesday. “It was 14, 17, back down again. I was quite concerned with the information I was receiving in terms of the inconsistencies.

“There were a number of questions I wasn’t prepared for … having the limited experience I had in those types of scenarios.”

The superintendent was also asked about the delay in informing the public that the killer was driving a replica police car. That information was confirmed by the RCMP by about 7:30 a.m. on April 19 but didn’t go out in a public tweet until 10:17 a.m. In that time, at least six people were killed.

A May 17 summary prepared by the mass shooting inquiry said there was an “ongoing investigation” into the role Leather played in releasing the information about the replica police car.

However, Leather said in an interview with the inquiry on July 6, which was released Wednesday, that he wanted the information to be released and didn’t in any way interfere with the communications staff who were working on preparing the alert.

“I was leaving it to the critical incident commander and communications staff to sort through …. If I was going to be brought into that conversation, they would have reached out to me. I didn’t insist on being part of that.”

Young also asked Leather about a phone call shortly after the murders, involving himself, RCMP Supt. Janis Gray and Truro police Chief David MacNeil.

In previous testimony before the inquiry, MacNeil said he was left with the impression the Mounties were concerned that an officer safety bulletin sent nine years before the killings — which warned officers that Wortman owned restricted weapons and wanted to “kill a cop” — would be made public as a result of freedom of information requests.

Young asked Leather whether during that phone call, he and Gray were “trying to bury the bulletin” to avoid criticism of the RCMP for not having investigated the killer in 2011.

“The opposite is true,” replied Leather, adding the call to McNeil was to let him know that RCMP investigators would be interested in speaking with the police officer who authored the bulletin.

“It was a very short call and it was more logistics-based,” Leather said. “Any threat to bring the command triangle (RCMP officers), to … look for records in their holdings doesn’t even make sense to me in terms of the nature of the conversation that we had.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published July 27, 2022.

— With files from Keith Doucette in Halifax.

Michael Tutton, The Canadian Press