Canada News

To prevent disasters like Lac-Mégantic, private interests cannot be allowed to affect regulations

Bruce Campbell, York University, Canada

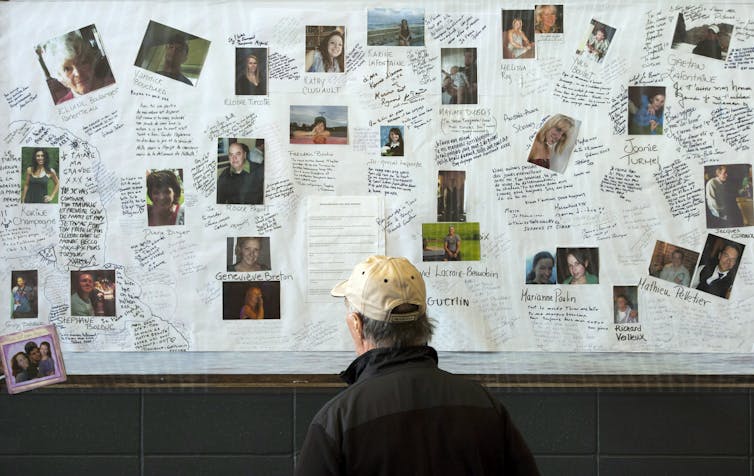

On July 6, 2013, the fourth deadliest railway disaster in Canadian history took place. A train hauling 72 tankers filled with crude oil derailed in Lac-Mégantic, Que., killing 47 people.

The roots of the Lac-Mégantic rail disaster can be traced to a combination of corporate negligence and regulatory failure. It is what spurred the publication of my recently edited volume about how Canadian corporations have co-opted government agencies for private interests.

Just prior to the disaster, the Canadian railway lobby had redrafted the Canadian Rail Operating Rules, permitting freight trains to operate with a single-person crew.

Transport Canada then granted permission to the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway — a company with a poor safety record — to run its trains through Lac-Mégantic with single-person crews.

This policy change was a significant contributing factor to the disaster. It exemplifies why regulatory capture is so dangerous and why it needs to be stopped.

Defining regulatory capture

Regulatory capture occurs when regulations are taken over, or captured, by the private interests of an industry, instead of being used to protect citizens’ health and safety, and the environment.

This primarily occurs when industries are the ones shaping policy, legislation and regulations, instead of the government. Industries often frame regulations as being detrimental to job and wealth creation. This enables them to block or delay new regulations, and exert pressure to remove or dilute existing ones.

The increase in regulatory capture can be traced back to Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s 2012 Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management policy that framed regulations as an administrative burden and a business cost that needed to be “streamlined.”

The policy’s centrepiece was the “one-for-one” rule, which mandated regulatory agencies to offset each new or amended regulation by removing at least one existing regulation.

The one-for-one rule put regulators in an awkward — and potentially dangerous — position. If regulators want to propose new regulations, they have to remove an already existing regulation, with potentially dangerous health and safety consequences. Unsurprisingly, this policy has resulted in catastrophic accidents and is in desperate need of reform.

Since the introduction of Harper’s policy, regulatory capture has spread far and wide in Canada. Experts in my edited volume illustrate how embedded it has become in various areas, from the pharmaceutical industry, as illustrated by pediatrician and clinical pharmacologist Michèle Brill Edwards, to the petroleum industry, as illustrated by the Corporate Mapping Project’s co-ordinator, William Carroll.

Confronting and overcoming regulatory capture

Until the Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management is reformed, regulators need to take the necessary steps to offset regulatory capture. My book offers concrete suggestions that regulators can follow to ensure regulations are once again made in the public interest.

As a result of regulatory resources being defunded over the years, many agencies have been forced to become dependent on corporations to develop and manage their own safety oversight regimes. To overcome this issue, regulatory agency resources must be bolstered, including hiring more personnel and increasing research capacity.

Regulators must also develop more robust conflict-of-interest provisions to clear up oversights, along with whistleblower protections.

In 2021, two international bodies ranked Canada in last place among 37 countries for the effectiveness of its whistleblowing frameworks. It is clear that we need to do better as a country.

Similarly, law professors Steven Bittle and Jennifer Quaid found that regulatory enforcement and accountability provisions have been hollowed out in Canada, allowing corporations to avoid serious legal liability — including criminal wrongdoing and corruption.

To counteract this, civil and criminal liability regimes must be reformed to hold senior government officials, corporate executives, directors and owners accountable for actions that result in accidents, destruction, illness and death.

Citizens must be involved

The vast majority of citizens expect their governments to take the necessary measures to protect their health, safety and environment. Understandably, opinion polls regularly indicate that the public does not trust corporations to regulate themselves.

Regulatory capture is likely to happen in a revolving door fashion, where people move seamlessly between private and public sector jobs and influence policies to suit the interests of both parties.

One way to stop the revolving door is by improving public access to information legislation. This would ensure that information shared between corporations and regulators under the veil of “commercial confidentiality” would publicly accessible.

Citizens should also be involved in the regulatory process, since regulations are supposed to be created to protect them. Effective public participation means the right to know, the right to participate in decision-making and the right to remedy or compensation for regulatory breakdowns.

Regulators should improve mechanisms for public participation in regulation-making processes, including online engagement.

Overcoming regulatory capture will require widespread mobilization, from citizens to members of industry alike. It will require a broad toolbox of collective actions from the public, including non-violent protest, advocacy, campaigns and more. Courageous parliamentary and bureaucratic leadership is also vital to achieving fundamental change.

At a time when the threat of potential disaster looms on the horizon, the stakes could not be higher. Last year — eight years after the Lac-Mégantic disaster — an auditor general report on railway safety expressed serious concern about defects in Transport Canada’s safety oversight regime. If we are to prevent future disasters from happening, regulatory capture must be overcome.

Bruce Campbell, Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.