Food

Surprise! There might be salmonella in your chocolate

In the past three months, more than 150 cases of salmonella food poisoning across Europe have been linked to Kinder chocolate products. Most of the cases have been in children under ten years old.

Health officials have traced the outbreak to bad milk in a factory in Belgium, and many products have been recalled from shelves as Easter approaches.

As consumers, we often think of the risk of food poisoning from raw or under-cooked meat, leftovers or even packaged salad. It’s less common to worry about chocolate.

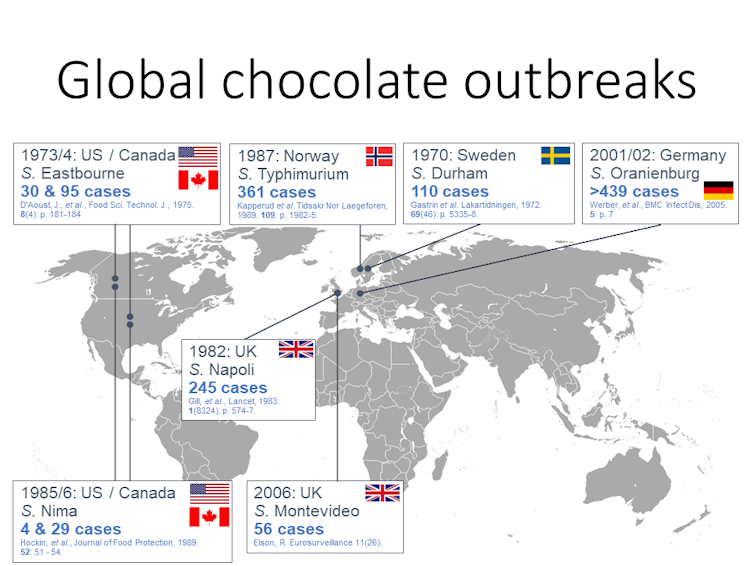

Salmonella outbreaks in chocolate

While reports of salmonella bacteria in chocolate are not common, there have been several high-profile outbreaks. Most documented cases of salmonellosis have been in Europe and North America, perhaps because chocolate consumption is high and monitoring and surveillance is in place.

Outbreaks include:

- 1970: cocoa powder contaminated with salmonella was used in confectionery products and subsequently caused an outbreak that affected 110 people in Sweden

- 1973–74: 95 cases of salmonellosis, acquired from Christmas-wrapped chocolate balls, were reported in Canada and another 30 in the United States

- 1982–83: a salmonella outbreak involving 245 people in the United Kingdom was traced to two types of chocolate bars produced in Italy

- 1985–86: 33 cases of gastroenteritis due to salmonella were reported in Canada and the US, and eventually traced back to chocolate coins imported from Belgium

- 1987: 361 confirmed cases of salmonellosis in Norway and Finland were part of an outbreak linked to chocolate contaminated with salmonella (it is estimated the actual number of infections was 20,000-40,000)

- 2001–02: an outbreak of salmonella occurred in Germany, resulting in at least 439 reports of infection, traced to a specific brand of chocolate distributed exclusively through a single supermarket chain

- 2006: an outbreak in the UK was traced to chocolate, with 56 cases reported.

Why do salmonella outbreaks occur?

Chocolate begins its life as various agricultural products, the most important of which is cacao. Much of the world’s cacao comes from small farms in West Africa.

Beans from the cacao tree are harvested, fermented and dried on these farms. There are plenty of opportunities for the beans to become contaminated with salmonella from animals and the environment.

When the beans reach a chocolate factory, they are roasted. This will kill any salmonella on the beans. But if salmonella is present on the raw beans it can potentially be a source of contamination.

It is important raw beans are well segregated from roast beans to prevent cross-contamination.

As well as this segregation, chocolate factories must be well maintained and have risk-control mechanisms in place. The 2006 outbreak in the UK, for example, was ultimately linked to water leaks from pipes onto chocolate.

Salmonella in chocolate

Even when chocolate is made using appropriate food safety techniques, it has inherent properties that make it very capable of spreading bacteria.

While salmonella will not grow in chocolate (there isn’t enough water), it survives in chocolate very well. Chocolate may even protect the salmonella during its passage through the gut.

This means a batch of chocolate product contaminated with salmonella may remain a food safety risk for a long time and be distributed over a large geographical area. This explains why chocolate-related outbreaks can affect large numbers of people in multiple countries.

Another important consideration is who often consumes chocolate: children. Children are often disproportionately represented in these outbreaks and may be more susceptible to severe infections.

What can be done?

Most confectionery manufacturers operate under stringent guidelines to ensure quality and safety of their products. Good manufacturing processes and food safety guidelines are well established to ensure chocolate is safe.

Manufacturers would prefer to eliminate pathogens (disease causing microorganisms) such as salmonella in chocolate, or at least detect it during manufacturing.

However, the current Kinder recall and others like it are evidence of the system working, albeit late in the process. When a recall notice is issued, consumers should take the advice seriously.

So don’t put off a little Easter indulgence! In the absence of a recall notice in a specific product, it is safe to assume eating chocolate won’t make you sick – unless perhaps you over-indulge.

David Bean, Senior Lecturer in Microbiology, Federation University Australia and Andrew Greenhill, Associate Professor in Microbiology and Fermentation Technology, Federation University Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.