Fashion and Beauty

‘I can only do so much’: we asked fast-fashion shoppers how ethical concerns shape their choices

You’ve found the perfect dress. You’ve tried it on before and you know it looks great. Now it’s on sale, a discount so large the store is practically giving it away. Should you buy it?

For some of us it’s a no-brainer. For others it’s an ethical dilemma whenever we shop for clothes. What matters more? How the item was made or how much it costs? Is the most important information on the label or the price tag?

Of the world’s industries that profit from worker exploitation, the fashion industry is notorious, in part because of the sharp contrast between how fashion is made and how it is marketed.

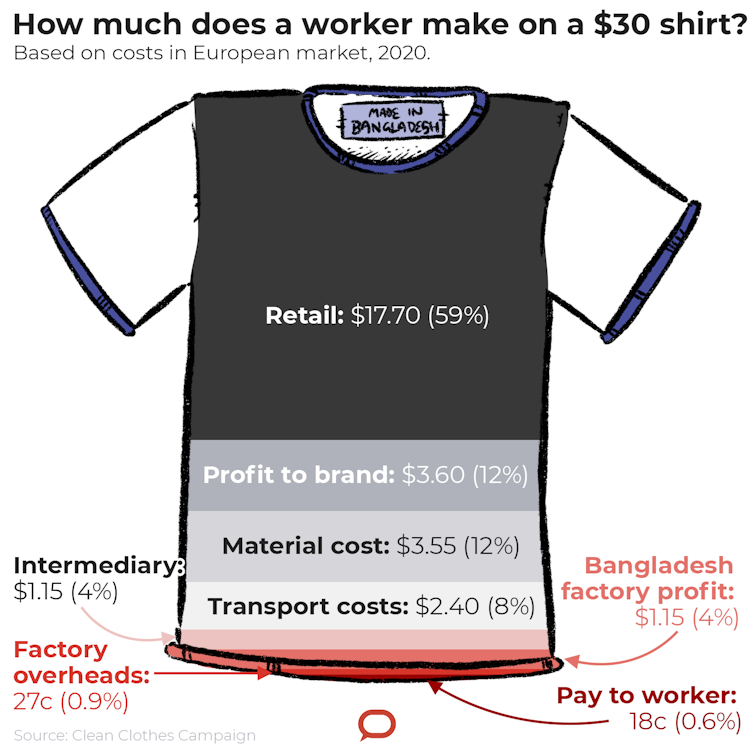

There are more people working in exploitative conditions than ever before. Globally, the garment industry employs millions of people, with 65 million garment sector workers in Asia alone. The Clean Clothes Campaign estimates less than 1% of what you pay for a typical garment goes to the workers who made it.

Some work in conditions so exploitative they meet the definition of being modern slaves – trapped in situations they can’t leave due to coercion and threats.

But their plight is hidden by the distance between the worker and the buyer. Global supply chains have helped such exploitation to hide and thrive.

Do we really care, and what can we do?

We conducted in-depth interviews with 21 women who buy “fast fashion” – “on-trend” clothing made and sold at very low cost – to find out how much they think about the conditions of the workers who make their clothes, and and what effort they take to avoid slave-free clothing. Well-known fast-fashion brands include H&M, Zara and Uniqlo.

What they told us highlights the inadequacy of seeking to eradicate exploitation in the fashion industry by relying on consumers to do the heavy lifting. Struggling to seek reliable information on ethical practices, consumers are overwhelmed when trying to navigate ethical consumerism.

Out of sight, out of mind

The 21 participants in our research were women aged 18 to 55, from diverse backgrounds across Australia. We selected participants who were aware of exploitation in the fashion industry but had still bought fast fashion in the previous six months. This was not a survey but qualitative research involving in-depth interviews to understand the disconnect between awareness and action.

Our key finding is that clothing consumers’ physical and cultural distance from those who make the clothes makes it difficult to relate to their experience. Even if we’ve seen images of sweatshops, it’s still hard to comprehend what the working conditions are truly like.

As Fiona*, a woman in her late 30s, put it: “I don’t think people care [but] it’s not in a nasty way. It’s like an out of sight, out of mind situation.”

This problem of geographic and cultural distance between garment workers and fashion shoppers highlights the paucity of solutions premised on driving change in the industry through consumer activism.

Who is responsible?

Australia’s Modern Slavery Act, for example, tackles the problem only by requiring large companies to report to a public register on their efforts to identify risks of modern slavery in their supply chains and what they are doing to eliminate these risks.

While greater transparency is certainly a big step forward for the industry, the legislation still presumes that the threat of reputational damage is enough to get industry players to change their ways.

The success of the legislation falls largely on the ability of activist organisations to sift through and publicise the performance of companies in an effort to encourage consumers to hold companies accountable.

All our interviewees told us they felt unfairly burdened with the responsibility to seek information on working conditions and ethical practices to hold retailers to account or to feel empowered to make the “correct” ethical choice.

“It’s too hard sometimes to actually track down the line of whether something’s made ethically,” said Zoe*, a woman in her early 20s.

Given that many retailers are themselves ignorant about their own supply chains, it is asking a lot to expect the average consumer to unravel the truth and make ethical shopping choices.

Confusion + overwhelm = inaction

“We have to shop according to what we care about, what is in line with our values, family values, budget,” said Sarah*, who is in her early 40s.

She said she copes with feeling overwhelmed by ignoring some issues and focus on the ethical actions she knew would make a difference. “I’m doing so many other good things,” she said. “We can’t be perfect, and I can only do so much.”

Other participants also talked about juggling considerations about environmental and social impacts.

“It’s made in Bangladesh, but it’s 100% cotton, so, I don’t know, is it ethical?” is how Lauren*, a woman in her early 20s, put it. “It depends on what qualifies as ethical […] and what is just marketing.”

Comparatively, participants felt their actions to mitigate environmental harm made a tangible difference. They could see the impact and felt rewarded and empowered to continue making positive change. This was not the case for modern slavery and worker rights more generally.

Fast fashion is a lucrative market, with billions in profits made thanks to the work of the lowest paid workers in the world.

There is no denying consumers wield a lot of power, and we shouldn’t absolve consumers of their part in creating demand for the cheapest clothes humanly – or inhumanly – possible.

But consumer choice alone is insufficient. We need a system where all our clothing choices are ethical, where we don’t need to make a choice between what is right and what is cheap.

The names of study participants have been changed to protect their anonymity.

Tara Stringer, PhD Candidate, Queensland University of Technology; Alice Payne, Associate Professor in Fashion, Queensland University of Technology, Queensland University of Technology, and Gary Mortimer, Professor of Marketing and Consumer Behaviour, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.