News

American religious groups have a history of resettling refugees – including Afghans

Since the Taliban took control of Afghanistan’s capital, Kabul, on Aug. 15, 2021, there has been a frenetic evacuation of foreigners and Afghan nationals. Thousands of these Afghans assisted the United States government, which now puts them in danger.

The United States provides a special immigrant visa to resettle such individuals. But applicants are facing long backlogs, and immigrant advocates have appealed to the Biden administration to increase the processing speed.

Many of these advocates are religious organizations. Since the April 2021 announcement of U.S. troop withdrawals, faith-based organizations like Lutheran Immigrant and Refugee Services, World Relief, National Association of Evangelicals and the Jewish nonprofit HIAS, have implored the Biden administration to evacuate Afghans. Faith-based voluntary agencies are preparing to receive as many Afghan refugees as possible.

This is part of a long history of religious involvement in refugee policy, in which most religious leaders support receiving refugees. However, as a refugee studies scholar, I have observed signs that such widespread support may be waning, particularly among white conservative Christians.

Religious advocacy on behalf of refugees

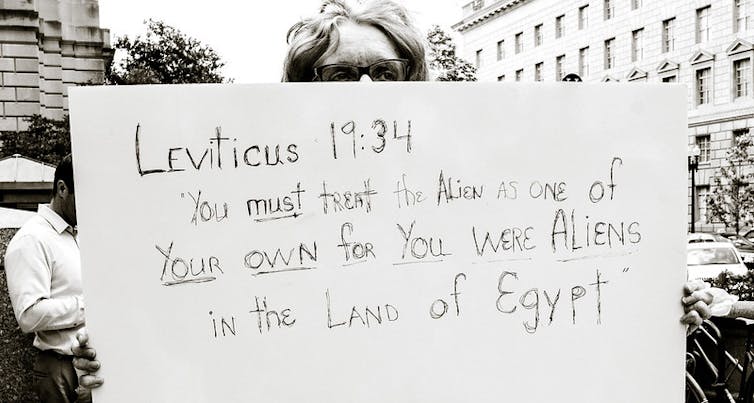

The idea of welcoming the stranger is central to Christianity, Judaism and Islam. It originally arose from cultures born in deserts, where leaving someone outside the city gates could be a death sentence. Religious leaders often connect that ethic to a responsibility to shield refugees and other immigrants from violence and oppression.

Starting in the late 19th century, and during the Holocaust, faith communities appealed to the U.S. government to welcome Jews seeking safety from persecution. They also advocated for allowing Armenians, who were murdered en masse by leaders of the Ottoman Empire, to immigrate to America.

After World War II, an alliance between Protestant, Catholic and Jewish organizations finally swayed policymakers to adopt a more humanitarian-focused U.S. foreign policy. The U.S. then joined with other nations to sign the 1951 Geneva Convention, a U.N. agreement that established the rights of refugees to legal protection.

Among the convention’s main tenets is a global ban on sending refugees back to countries where they will be unsafe. This sometimes requires resettling refugees in a safer country. Faith-based organizations have been partnering with the U.S. government ever since.

The sanctuary movement

Between 1951 and 1980, the government resettled refugees in the U.S. on an ad hoc basis without spending much on assisting them. During this time, faith-based organizations filled in gaps to ensure refugees got off to a good start.

Religious groups also advocated for asylum seekers, people who arrived seeking protection without first getting refugee status. Between 1980 and 1991, almost 1 million Central Americans crossed the U.S. border seeking asylum. From the start, the government denied most of their petitions.

Many Christian and Jewish leaders advocated on behalf of these migrants. They preached sermons, lobbied the government and organized protests calling for protecting Central American asylum seekers. Hundreds of religious communities provided sanctuary, usually inside houses of worship, and gave them legal support.

In 1985 the Center for Constitutional Rights sued the federal government on behalf of the American Baptist Church, Presbyterian Church USA, the Unitarian Universalist Association, the United Methodist Church and four other religious organizations, claiming discrimination against Salvadoran and Guatemalan asylum seekers. The government later settled the class-action lawsuit, allowing temporary protection for those asylum seekers.

Faith-based nonprofits supporting refugees today

Ever since Congress passed the 1980 Refugee Act, creating the current system of refugee resettlement, U.S. faith-based organizations have played a central role in it.

There are nine national voluntary agencies that work directly with the government, six of which are faith based: One is Jewish, one Catholic, one evangelical Christian and three are mainline Protestant. These groups arrange for refugees to find housing, land jobs and enroll in English classes. They do so regardless of the newcomers’ own religions or their countries of origin.

In my research, I have found that staff at faith-based organizations commonly use religious rhetoric to justify their work and to describe their commitment.

At the same time, religiously based refugee organizations frame their efforts using interfaith language. They invoke the ethical imperative to provide asylum and refuge in ways that cross-cut multiple religious traditions as they collect and disburse money and household goods – and mobilize volunteers.

“The Jewish dimension is helping people realize that America is a place that welcomes all, and helping people that have come from a land where maybe sometimes being a Jew was considered worse than dirt,” a director of a local office of HIAS, formerly known as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, told me. “Do we apply those same kinds of principles to other communities that we help? Absolutely.”

The director of a Catholic Charities office echoed that sentiment. “We have a saying,” he told me. “We help people not because they are Catholic, but because we are.”

Changing religious politics?

Despite the deep foundation of religious belief and morality for granting asylum, this connection may have frayed, at least for some communities. In response to a record number of people displaced globally, especially people who are not white, I’m seeing signs that the moral framework supporting asylum is giving way in some quarters to support for restrictive policies that avoid any moral or international obligation to asylum seekers.

This became clear when the Trump administration enacted its “zero tolerance” policy to arrest anyone crossing the border without documentation – including people with babies and toddlers. Government agents and contractors separated nearly 4,000 children from their parents, sparking outrage.

Many faith leaders spoke out against the child separation, like prominent evangelical leader Franklin Graham, without directly criticizing aggressive border enforcement. But many were more pointed in their comments, specifically calling out immigrant exclusion as antithetical to their religious beliefs. Mainline Protestant, Jewish, Mormon, Catholic and evangelical Christian groups all released statements against tighter immigration enforcement itself.

What was unusual is that some conservative Christian groups lobbied in favor of strengthened immigration enforcement. This was a break from the past. While there have been theological differences between conservative and mainline Protestant Christians on a number of issues, welcoming the stranger had been one point upon which Christians generally agreed.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

Race and racial politics are intertwined with this split. There now appears to be an inverse relationship in the U.S. between religious identity and support for asylum among white Americans. In a Pew survey conducted in May 2018, only 43% of white Protestants and 25% of white evangelical Christians thought that the U.S. had a responsibility to accept refugees. Conversely, 63% of Black Protestants and 65% of the religiously unaffiliated thought that the nation has that responsibility.

It is unclear whether this represents an overall downward trend in white Christian support for people seeking safe haven. Faith leaders and those working in faith-based resettlement organizations that I have spoken with recently enthusiastically support accepting as many Afghan refugees as possible. Whether there will be such support broadly among Americans of faith remains to be seen.

This is an updated version of a piece originally published on Oct. 31, 2018![]()

Stephanie J. Nawyn, Associate Professor of Sociology and Co-Director of the Center for Gender in Global Context, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.