Uncategorized

Climate action, job creation are top post-pandemic priorities for Canadians

Since March 2020, the federal government in Canada has provided large-scale pandemic relief and economic stimulus, while the Bank of Canada has kept interest rates near zero and made large purchases of government bonds.

These extraordinary measures have their critics, but few would dispute the fact that they have helped keep the economy afloat and protect Canadians’ incomes.

Now what? Should we turn our attention to our newly acquired debt and focus on restoring business confidence, or do we “build back better” by investing in a social equity and climate change agenda?

As competing voices urge different priorities, we asked a random sample of Canadians two questions: What should Canada’s broader economic priorities be going forward? And what should the next federal budget focus on?

In January 2021, we conducted a national survey of 563 respondents across all 10 provinces. The survey had a margin of error of between plus and minus 4.13 per cent, 19 times out of 20. Initial findings from the survey are further explored in a policy brief issued by the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Saskatchewan.

Creating jobs a top priority

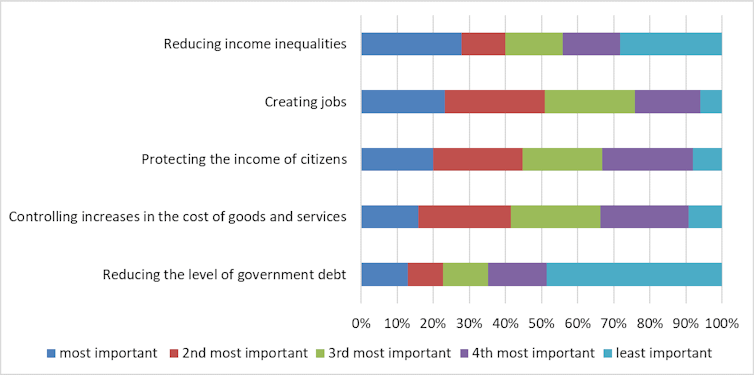

Creating jobs and controlling inflation have been traditional goals of economic policy, and we expected our respondents to recognize them as legitimate policy priorities. But what about the debt? To gauge our respondents’ sense of the relative importance of different goals, we asked them to rank the five economic policy priorities from the most to the least important.

About 50 per cent of our respondents think that “creating jobs” should be either the first or second economic priority as we emerge from the pandemic. Fewer, but more than 40 per cent, think that controlling inflation (“controlling increases in the cost of goods and service”) should be the first or second priority. Very few, less than 10 per cent, see creating jobs and keeping inflation under control as the “least important” priorities.

Our respondents are sensitive to income issues. While 20 per cent think that “protecting the income of citizens” should be the most important priority going forward, an even larger proportion endorsed “reducing income inequalities.” Almost 30 per cent of respondents, in fact, ranked closing income gaps as the most important policy priority.

These preferences signal a willingness to support active measures to shape income distribution. And if that means taking on more public debt, so be it. The traditional public finance goal of “reducing the level of government debt” received support from less than 15 per cent of respondents — and almost 50 per cent chose it as the least important of the five proposed priorities.

In short, reducing income inequality and creating jobs were ranked the top two most important economic policy priorities, regardless of age, gender, region of residence or household income. The only exception to this homogeneous response involves the importance of “creating jobs.” Seniors aged 65 and up, men, and residents in Atlantic Canada all ranked “creating jobs” as a more important policy priority than “reducing income inequalities.”

Budget priorities

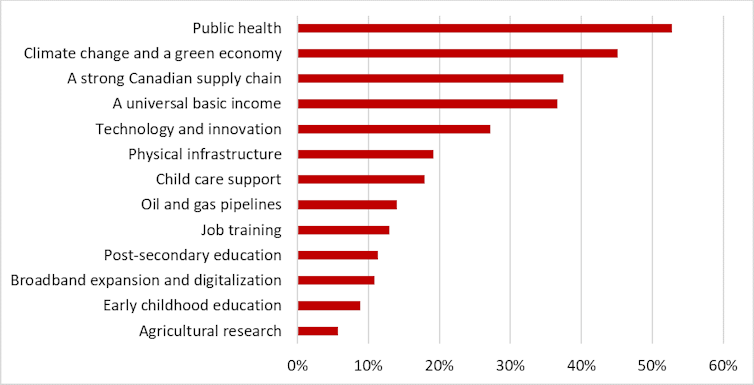

Economic priorities are quite general, but budget priorities reveal the specific investment preferences of governments. To gauge how ordinary Canadians might approach budget priorities, we provided our respondents with a number of possible priority areas and asked them to identify the three areas they deemed most deserving of support — and the three areas least deserving.

It comes as no surprise to learn that Canadians believe public health initiatives deserve high priority. But perhaps the clearest message for our post-pandemic future is to be found in the second most important priority: Climate change and the green economy.

This preference is shared by respondents across an array of different demographic and regional groups. Given signals contained in the federal government’s 2020 Fall Economic Statement, climate action may be one area where public priorities and political messaging are converging.

With their endorsement of strong Canadian supply chains and technology and innovation, the graph above also suggests respondents recognize the importance of a positive environment for business investment, the principal concern of Canada’s business-oriented think tanks.

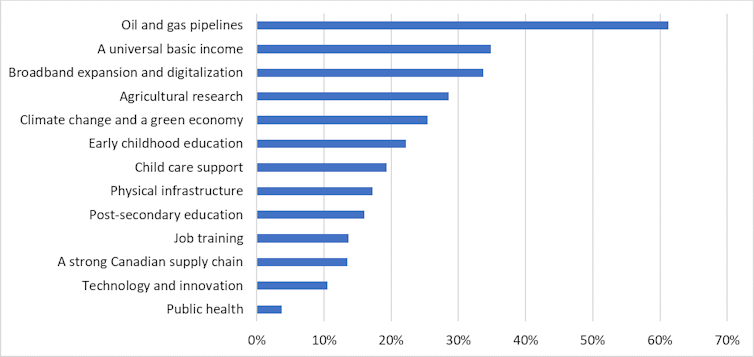

More worrying, from a long-term investment perspective, is the relatively low priority accorded to education, whether job training, post-secondary or early childhood. The next graph shows that more than 20 per cent of our respondents list early childhood education among the least important priority areas.

And speaking of the lowest-ranked priorities — those deserving the least support — oil and gas pipelines lead the way by a wide margin. Respondents living in central Canada (Ontario and Québec) are slightly more inclined to label pipelines “least deserving,” but the regional differences are not large. If this choice is the flip side of the green economy preference, the message is quite clear: Canadians are looking toward a post-fossil fuel economy.

Some budget priorities are more ambiguous. “A universal basic income” is a good example of a policy preference embraced by a large segment of our respondents and rejected by an almost equally large segment. It will not be easy to find a middle ground.

Priorities could shift

The results of our survey represent a snapshot in time. We have probed priorities, but priorities change.

As Canada emerges from the pandemic, creating jobs and achieving full employment are top priorities. Relegated to the back burner are traditional concerns for balanced budgets and declining debt levels.

Expect priorities to shift if inflation increases and interest payments on the debt begin to threaten the programs Canadians take for granted. Support for a green economy and reducing income inequalities are likely to be more durable preferences. The same goes for antipathy towards oil and gas pipelines.

But opinions are not uniform and governments will face pockets of resistance on almost all their initiatives.

Michael M. Atkinson, Public Policy Professor Emeritus, University of Saskatchewan and Haizhen Mou, Professor, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy, University of Saskatchewan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.