News

Joe Biden’s empathy may result in a ‘therapeutic’ foreign policy

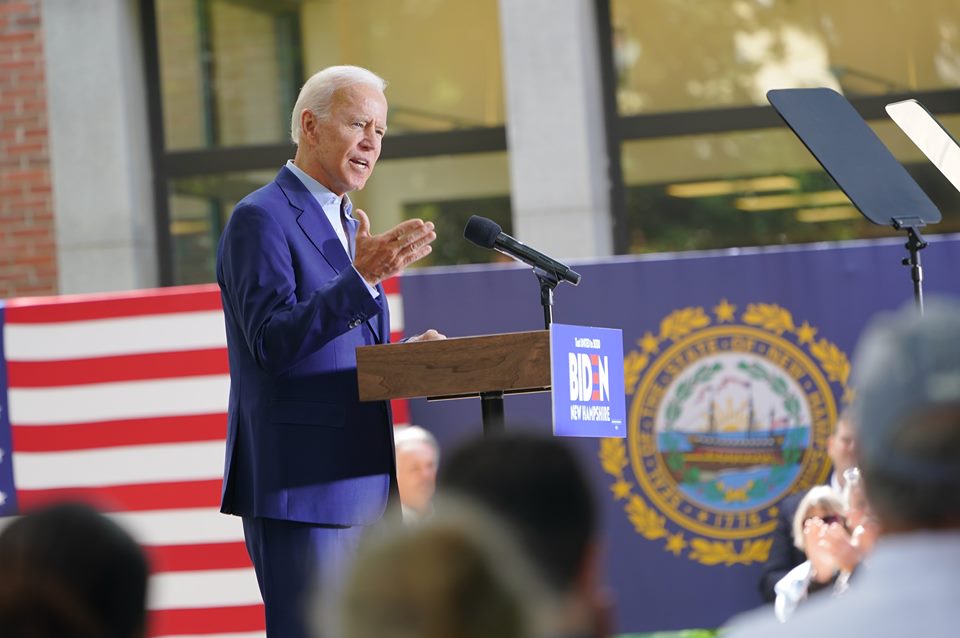

Historians are generally far more accurate at parallels than predictions. So let me draw two admittedly imperfect but analogous historical examples that might help guide a therapeutic Biden foreign policy. (File photo: Joe Biden/Facebook)

Both in the United States and abroad, President-elect Joe Biden finds himself with the unenviable task of trying to reverse the psychological and emotional effects of “post-Donald Trump stress disorder” that has set in over the last four years.

Although foreign policy received scant attention from the candidates during the election campaign, the international wave of congratulations pouring in for Biden and Kamala Harris (and the few notable holdouts) show that the world is paying close attention.

And so, it seems like an opportune time to ask a simple question: what now?

My suggestion: therapeutic diplomacy.

Emotions and foreign policy

I don’t mean literal therapy, though that’s been recommended in some diplomatic impasses. Rather, I mean paying more attention to psychology and emotions to mend global relationships.

No foreign policy-maker should dismiss emotions. And no foreign policy-maker is ever above emotions.

Even the prince of realpolitik himself, Henry Kissinger, former U.S. secretary of state and national security adviser, talked a lot about feelings and psychology.

Two examples: During the India-Pakistan crisis of 1971, Kissinger saw supporting Pakistan as an attempt to “prevent a complete collapse of the world’s psychological balance of power.”

And when selling the ill-fated “Year of Europe” to European partners shaken by détente with the Soviet Union, he explained to the French foreign affairs minister that he sought to “create an emotional commitment in America.” All this talk of feelings unfolded under Richard Nixon, once referred to as “the first therapeutic president.”

Kissinger should not provide a road map for Biden, who can aim higher. But Biden, who is performing well as an emotional manager in the days since Nov. 3, calmly urging patience and compassion, seems ideally suited to this therapeutic task given that empathy has been described as his “superpower.”

Historians are generally far more accurate at parallels than predictions. So let me draw two admittedly imperfect but analogous historical examples that might help guide a therapeutic Biden foreign policy.

The spectre of communism

The winter of 1947, one of the harshest on record, witnessed a still-devastated post-war Europe starting to look to communist parties for answers to basic survival.

In this volatile Cold War context, U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall pitched the European Recovery Program in the spring. It attended to more than the economic needs of European allies — it also targeted their demoralized psyches.

According to Marshall’s speech unveiling the plan:

“Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.”

Between 1948 and 1952, the $13-billion Marshall Plan, as it became known, invested in the oversimplified calculation that happy, prosperous people don’t turn to communism. And it paid off handsomely, forming the basis of one of the longest periods of economic growth in history and creating mutual trust among allies for years to come.

The spectre of COVID-19

With Biden now set to take the helm during what promises to be an equally harsh COVID-19 winter, a similar approach to the global pandemic is conceivable. An analogous Joe Biden-Kamala Harris COVID-19 plan that pledges to share the vaccine could help attend to the world’s health needs, both physical and psychological.

And it might restore some trust with allies, slowing down the already wary drift of friends in Asia into Beijing’s orbit or emboldening NATO partners to stand up to Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

This is not to say that the coronavirus crisis should be seen as an opportunity — taking an international approach to the vaccine is simply the right thing to do. But the psychology of moral leadership may be significant in dealing with the rise of “authoritarianism in the time of COVID-19.”

Trump’s “America First” policies have meant racist travel bans, white supremacist talk of “shithole countries,” running roughshod over allies and embracing authoritarian leaders. Four years of bluster and bullying have had a demoralizing effect, leaving U.S. friends feeling insecure and foes feeling emboldened — and everyone in between feeling disoriented.

The U.S. as a force for good

Biden himself has referred to an “Obama-Biden” foreign policy.

Like Biden, Barack Obama had to pick up the pieces of a broken foreign policy bequeathed by his predecessor, George W. Bush: a global recession and a sprawling U.S. war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan.

After years of Islamophobia and talk of “crusades” against terror, the Obama approach was also therapeutic: soothing hurt feelings and reminding the world, especially those in the Middle East, that at its best, the U.S. could be a force for good.

This tonal shift is perhaps best captured by two words uttered by Obama in Cairo in 2009: “Assalaamu Alaykum.”

Using an Arabic greeting (“peace be upon you”) captured Obama’s goal, outlined in his speech, of ushering “a new beginning between the United States and Muslims around the world, one based on mutual interest and mutual respect, and one based upon the truth that America and Islam are not exclusive and need not be in competition. Instead, they overlap, and share common principles — principles of justice and progress; tolerance and the dignity of all human beings.”

Obama’s conservative response to the 2011 Arab Spring provided a stark example that he never fully lived up to the promise of those two words: there were limits placed on U.S. support for “justice and progress.” But neither did pro-democracy protesters witness the U.S. at its interventionist worst.

Post-Trump therapy?

It’s possible to imagine Biden playing the role — perhaps even better than a sometimes aloof Obama — of an emotion-focused therapist for the rest of the world, mending strained global relationships.

His emphasis on healing in his victory speech suggests he’s likely up for the task.

Biden is not a saviour, however, and a return to “normalcy” is not enough. But a therapeutic Biden foreign policy might well go a long way in staving off what some have called the “end of the American Century” by easing tensions around the world stoked by Trump.![]()

Matthieu Vallières, Sessional Lecturer in History, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.