Business and Economy

Facebook profits from Canadian media content, but gives little in return

For the first two quarters of 2020, Facebook reported revenues of US$924 million in Canada alone. Over 2018 and 2019, Facebook made nearly $6 billion in Canada. (File photo: Brett Jordan/Unsplash)

It’s a promise I can’t wait to see fulfilled. In its most recent speech from the throne, Justin Trudeau’s government pledged to ensure the revenue of web giants “is shared more fairly with our creators and media.”

As a journalism professor, I think that’s great news for Canadian journalists. Canadian media have been struggling in the past decade — and more than 2,000 jobs have been lost since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But how much will the contributions from digital platforms amount to? How can we calculate what news is worth for them?

Putting a dollar value on news

I’ll focus on Facebook, both because we can extract Canadian revenues from its financial documents and also because it doesn’t have a revenue-sharing model.

For the first two quarters of 2020, Facebook reported revenues of US$924 million in Canada alone. Over 2018 and 2019, Facebook made nearly $6 billion in Canada.

It should be noted that nearly 98 per cent of this turnover comes from advertising sales — it’s the same good old business model that has sustained news media for the past 200 years, but Facebook has tailored it for the digital age using emotional manipulation.

To find out what proportion of this attention is the result of journalistic content, I used CrowdTangle, a public insights tool offered by the company to look for content on Facebook, Instagram and other social networks such as Reddit. Researchers have been able to access it since 2019, under a partnership with Social Science One.

Among other things, CrowdTangle provides access to the 30,000 publications that generated the most interactions over a given period of time. Interactions are the sum of shares, reactions (like, love, wow, haha, anger, sadness and, more recently, care) as well as comments. The tool also allows you to restrict your search to pages administered in a given country.

Calculating profit

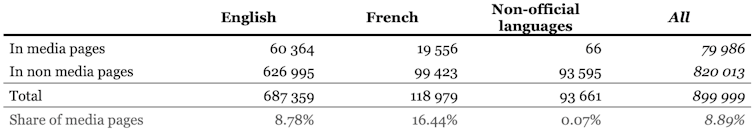

For each of the 30 months in the period between Jan. 1, 2018, and June 30, 2020, I used CrowdTangle to identify the 30,000 posts that generated the most interactions on pages whose administrators are predominantly located in Canada. I got 900,000 Facebook posts from just over 13,000 different pages. Of these, close to 500 pages belong to news media. Together, they posted almost 80,000 items.

This means media pages have accounted for 8.9 per cent of the Canadian content on Facebook pages. This proportion of the company’s Canadian sales represents more than half-a-billion dollars since 2018.

(Jean-Hugues Roy), Author provided

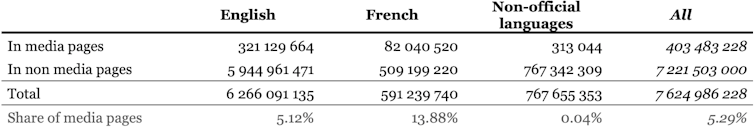

Having said that, we must take into account the fact that Facebook does not generate revenue simply when a post is published, but when people interact with this content by sharing it, liking it or commenting on it. So let’s take a look at how interactions are distributed by language and page type since Jan. 1, 2018.

(Jean-Hugues Roy), Author provided

Out of more than 7.6 billion interactions, more than 400,000 were triggered by journalistic content. That’s 5.3 per cent of the total.

This way of calculating, which weighs the place of journalistic content by the lowest number of interactions it generates, still means that the Canadian media have enabled Facebook to raise nearly a third of a billion dollars over the past two and a half years.

The gulf between Facebook and the media

Of course, my study has its limits. Facebook generates revenue in Canada when advertisers buy ads to reach Canadians. In order to more accurately measure Facebook’s revenues in Canada, it would be necessary to examine what content Canadians are viewing on this social network. But Facebook does not share this kind of information. The best we can do, therefore, is to look at what is produced by pages administered in Canada.

Besides, it’s not only pages on Facebook. There is also content on groups and profiles. And Facebook generates revenue through Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp. But it is only possible to collect country data through the pages.

The main takeaway from this analysis is that there is a gulf between what the media allow Facebook to generate as revenue and what Facebook returns to them. Kevin Chan, director of public policy for Facebook Canada, stated in Le Devoir recently that Facebook has spent $9 million on various journalism projects in Canada over the past three years.

Sharing revenue

There are other ways Facebook benefits the media — they can monetize their stories through “instant articles,” where content remains on Facebook in exchange for some revenue sharing with the media, or the video platforms Watch and IGTV, Facebook’s attempts to compete with YouTube.

In the United States, Facebook News, a new licensing mechanism, could allow some major media outlets to earn up to US$3 million annually.

Facebook also funds some journalism education initiatives at various universities, including Ryerson University.

However, instant articles have been abandoned by many media outlets, and creators trying Watch have gone back to YouTube. In both cases, it’s because Facebook doesn’t share enough of its revenue.

Australia introduced legislation that would force Facebook and Google to sit down with the Australian media and negotiate to share revenues. Canadian Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault seems to have been inspired by this approach.

Facebook benefits from journalism

Facebook has reacted to Australia’s intentions by threatening to block users from sharing local and international news. Just imagine Facebook without news: Would we use it as much if all we could share with our friends was clickbait?

Making Facebook share its revenues would therefore be a triple win. First, with a little more money, the media would be able to hire more journalists. I say “a little” because I know Facebook alone won’t save the media, but it would certainly help.

Second, the federal government (and all Canadians) would win too, because supporting the production of quality journalism is a concrete way to fight misinformation.

Third, Facebook would win because Canadians would have greater assurance that it would be a source they can trust for their information needs.![]()

Jean-Hugues Roy, Professeur, École des médias, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.