Health

Blaming women for breast cancer ignores environmental risk factors

(National Cancer Institute/Unsplash)

Amidst the conversations about COVID-19 there seems to be increasing attention to the health risks many workers face in their jobs. I find hope in this growing regard for workers’ health and safety.

For women who work at the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor, Ont., the hope is that public awareness of their risks for cancer and other health problems would lead to changes for safer working conditions. Perhaps now with wider conversations about protecting workers at risk, the women at the Ambassador Bridge can see their concerns about a suspected cluster of breast cancer addressed.

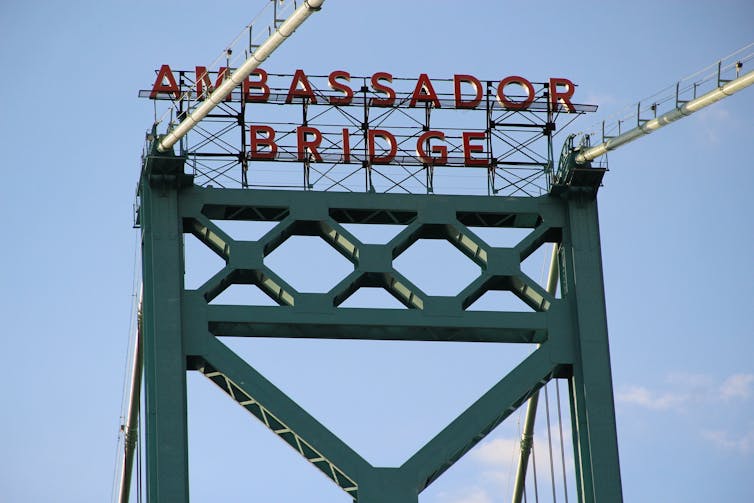

(cmh2315fl/flickr), CC BY

Ambassador Bridge connections

Growing up in Windsor, I recognized the Ambassador Bridge as a defining feature of the landscape. Spanning more than two kilometres, it connects Windsor to Detroit in the United States. I later understood its significance in global trade, politics and environmental issues in the wake of 9/11 with heightened security and increased restrictions.

The Ambassador Bridge also has an important role in work for environmental health and justice: the women who work there face high rates of breast cancer. In interviews with women who worked at this border crossing, I listened to their personal stories as they talked about the complex risk factors for breast cancer. Largely unheard, these women’s stories are a new landscape and a symbolic bridge to cross in efforts for environmental breast cancer prevention.

Sorting out evidence

Breast cancer is an international public health issue. Much of the messaging on breast cancer suggests women’s individual lifestyle factors are to blame. This approach blinds us to underlying social and structural influences on breast cancer — namely environmental and workplace conditions and exposures, and health inequalities.

Environmental breast cancer is still in many ways a contested illness despite increasing evidence of links to workplace and environmental exposures. It is widely viewed as a disease of lifestyle or bad luck .

Breast cancer policy reflects this focus:

Fourteen Canadian women die each day from breast cancer. One in eight women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime. There are about 500 new diagnoses per week, and the incidence is rising in younger women. Worldwide, almost 630,000 women died from breast cancer last year. Up to 70 per cent of breast cancers may originate environmental contaminants.

Missing puzzle pieces

Environmental and occupational risk factors don’t get the same attention as individual risks. To prevent more breast cancers, research and risk strategies should include gender, racialization, social class, ethnicity, migration status, geographic location, environment and occupation among other contributions to inequalities in risk.

Canada does not systematically collect data on race and ethnicity for breast cancer, among many other data gaps in health. In order for public health policy and primary prevention to be effective, these factors, in addition to lifestyle and genetics, need to be addressed.

There has been some progress made around the issue of environmental breast cancers: recent research identifying exposures in the workplace and general environments; community organizations and campaigns focused on social and environmental risk factors; films and books addressing the issue; academic research on social disparities; the American Public Health Association’s Policy Statement on Breast Cancer and Occupation; and global networks working towards prevention of environmental breast cancers. These are all necessary in addressing the complexity of social conditions for breast cancer prevention.

Trusted sources

In my research with women workers at the Ambassador Bridge, their information sources were a key piece of interest. Whether the messages about breast cancer causality and prevention come from mainstream media, internet sources, family, friends, doctors, co-workers or personal experiences, they influenced how women understand the issue of breast cancer risk. As research shows, much of the messaging on breast cancer omits environmental and social risks, and primary prevention .

The women at the Ambassador Bridge also describe how they see their work environment as a contributor to the high rates of breast cancer there. They mentioned diesel exhaust, air pollution, shift work, stress and the lack of power over their conditions. This knowledge from their experiences runs counter to the dominant messages.

The women’s stories also bring out how they feel powerless to reduce or stop environmental risks for breast cancer. They believe that a formal investigation into the number of cases should be carried out.

Shifting blame

Will this moment of facing workers’ health risks amid COVID-19 represent a shift to taking workplace health risks seriously, including for breast cancer?

Can we build global support for improved health and safety for women, including those who work at the Ambassador Bridge, a century-old steel span bridge that has long been a symbol of connection?

The social conditions of breast cancer are important. Blaming women for their breast cancers while ignoring workplace and environmental risks is a failed approach. Deeply entrenched institutional risks for breast cancer must be challenged to build an effective public health strategy towards primary prevention of breast cancer.![]()

Jane E. McArthur, Doctoral Candidate in Sociology, University of Windsor

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.