News

103-year-old ex-chemist to be honoured for work on penicillin

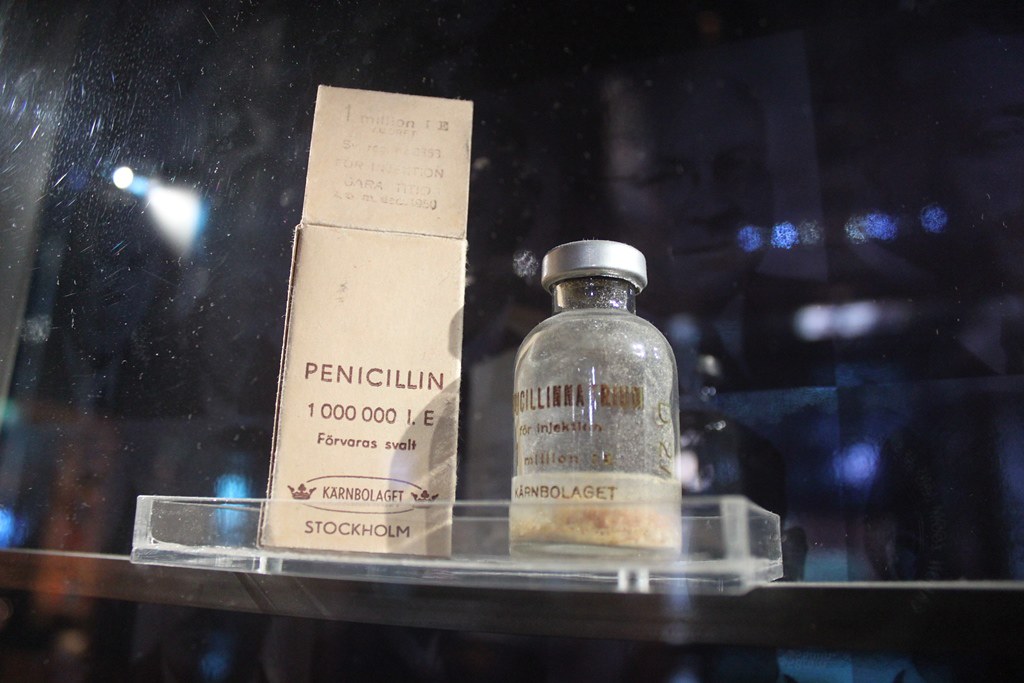

The antibacterial properties of penicillin were first identified in a British laboratory in 1928, but it wasn’t until 1941 that it was tested on humans with promising results. Unable to mass-produce penicillin because of the war, Britain turned to the U.S. government and U.S. manufacturing companies, including Merck, Pfizer, Squib and others. (File Photo: Solis Invicti/Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

COLUMBUS, Ohio — The story is family lore. In 1942, chemist Robert Walton, then in his late 20s, was drafted following the attacks on Pearl Harbor and boarded a bus in Rahway, New Jersey, for basic training at Fort Dix.

His journey lasted only a few miles (kilometres) when FBI agents boarded the bus and explained that Walton had to return to work at his laboratory at nearby Merck & Co. His mission: to expand supplies of penicillin.

“Audrey wasn’t even surprised when I went back for supper,” Walton, now 103, recalled of his young wife’s nonchalant reaction when he walked through the door that night.

Walton and his legacy recently caught the eye of the Columbus chapter of the Military Order of The Purple Heart, which asked him to lay a wreath at the group’s monument at the National Veterans Memorial and Museum in Columbus on Aug. 7, which is national Purple Heart Day.

The work Walton and others did saved millions of lives, said chapter head Tom Beck, a Korean War veteran wounded during a mine-clearing operation in January 1953.

“All we want to do is make sure he knows that there are people who appreciate his work,” said Beck, 86, a retired teacher in suburban Columbus.

The antibacterial properties of penicillin were first identified in a British laboratory in 1928, but it wasn’t until 1941 that it was tested on humans with promising results. Unable to mass-produce penicillin because of the war, Britain turned to the U.S. government and U.S. manufacturing companies, including Merck, Pfizer, Squib and others.

The government took over all production of penicillin when war broke out. Using corn steep liquor, a waste product from producing corn starch, researchers at a U.S. Department of Agriculture lab in Peoria, Illinois, helped boost supplies.

The ensuing results showed the power of war time machinery, said Robert Gaynes, an Emory University professor and physician and an expert on the history of penicillin’s development and production.

In 1941, the United States did not have enough penicillin to treat a single patient, Gaynes wrote in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases in 2017. “By September 1943, however, the stock was sufficient to satisfy the demands of the Allied Armed Forces,” he wrote.

“To have produced that much that fast is a tribute to everyone involved,” Gaynes said in an interview last week.

Walton, who later earned his PhD from Rutgers University, spent a 40-year career with Merck in New Jersey, retiring “some time ago” he said with a smile, sitting in his daughter’s home. (In 1981, to be precise.)

His many accomplishments include a patent for Pneumovax, a pneumonia vaccine. He moved to Columbus a few years back following the death of his wife after 73 years of marriage.

His daughter, Wendy Walton Reichenbach, 67 and also a retired chemist, wrote a first-person account of her father for The Columbus Dispatch last month, explaining the family’s pride in his work.

“On a recent patriotic holiday, I thanked my dad ‘for his service to our country,’ as I do almost every year,” she wrote. “His response — ‘If you say so’ — has been the same every year for decades. He has never felt that he ‘served.”’

Walton was hard pressed to describe his war-time service in anything beyond clinical terms, recounting the meticulous work to develop mediums for the submerged growth of penicillium — the mould — which was crucial for large-scale penicillin production.

He expressed surprise at the Purple Heart group’s admiration of his work and desire to honour him.

“Well, it was just my job,” he said.

———

Associated Press researcher Jennifer Farrar in New York City contributed to this report.