Entertainment

‘Anything You Can Imagine’ recounts quest to film Tolkien

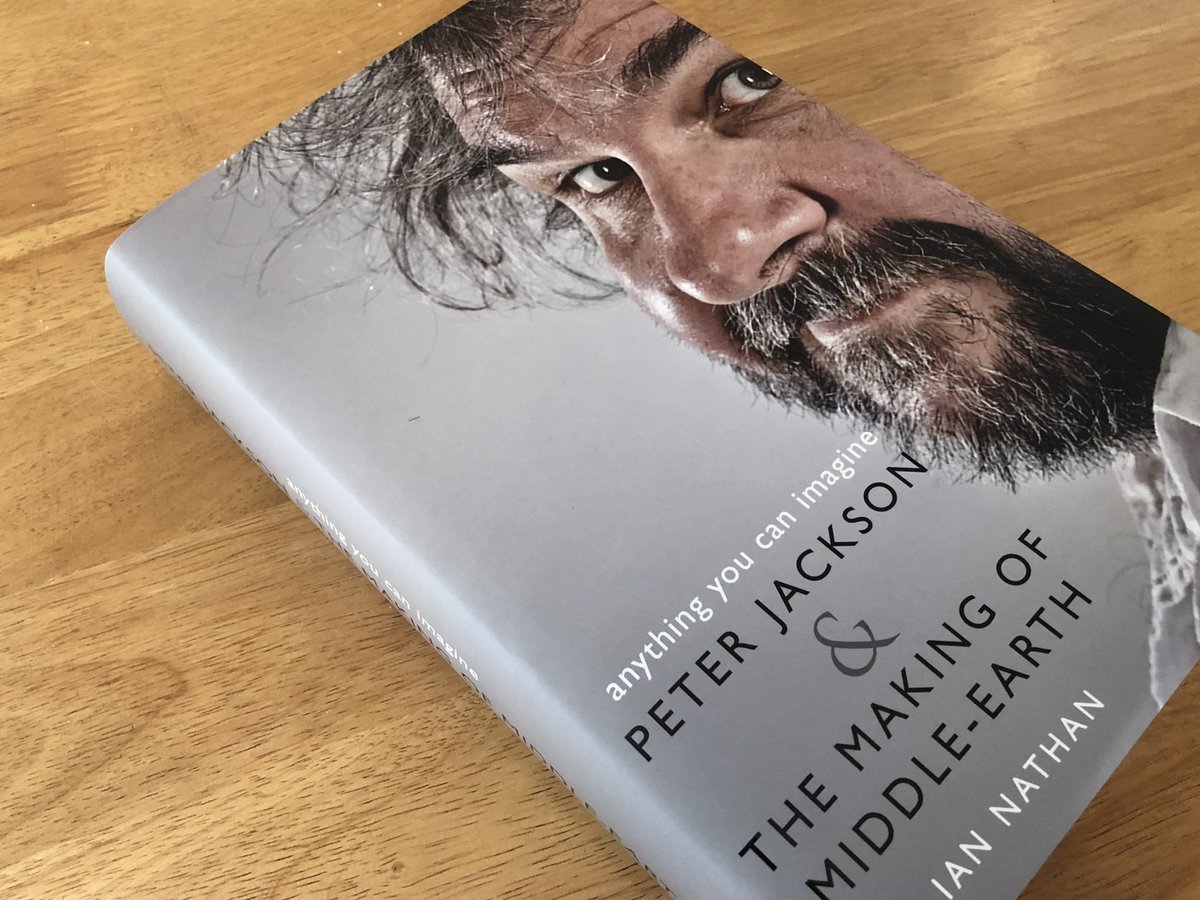

Jackson’s movies are a marvel of cinematic storytelling, likely to remain so because he came to understand that the special effects should be deployed not just to thrill but also to give emotional life to novelist J.R.R. Tolkien’s world. (File Photo: @IanNathan2/Twitter)

“Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson & the Making of Middle-earth” (HarperCollins), by Ian Nathan

Reaching the final sentence in film writer Ian Nathan’s 576-page exploration of movie director Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy requires the stoicism of Frodo and the vigour of Gandalf. So much detail lies along the way that even the eye of Sauron would need a shot of Visine to keep going.

That shouldn’t put off fans of the films that, collectively, gained 30 Oscar nominations and 17 of the golden statuettes, including a Best Picture award for the finale, 2003’s “The Return of the King.” Oh, and they left behind a worldwide box office stuffed with a couple billion dollars, too.

Jackson’s movies are a marvel of cinematic storytelling, likely to remain so because he came to understand that the special effects should be deployed not just to thrill but also to give emotional life to novelist J.R.R. Tolkien’s world. (It’s an epiphany that Jackson apparently forgot with the bloated “King Kong” and his overstretched LOTR follow-up, “The Hobbit.”)

In breezy and often cheeky prose, Nathan tells a grand story worthy of the annals of great filmmaking: A little-known New Zealand director wins over Hollywood moneymen to translate Tolkien to film, once thought to be an impossible task given the complexity of Tolkien’s vision of a place called Middle-earth and the hobbits, wizards, dwarves, elves and others who inhabit it.

Tolkien himself shrugged off the idea of a movie version in the late 1950s. A decade later, in 1967, his books enormously popular on college campuses, the aged Oxford professor accepted 104,000 British pounds for the film rights in (gasp!) perpetuity. In hindsight, it’s enough to make an orc cry.

For decades, however, Tolkien’s folly appeared to be a good deal as one effort after another failed and the rights became a cinematic albatross. The most fanciful idea may have come from the Beatles, who asked “2001” director Stanley Kubrick to join them in presenting a music-infused version with Paul as Frodo, George as Gandalf, John as Gollum and Ringo as Sam (so reports Jackson after a chat with McCartney).

The hero of the quest to film “The Lord of the Rings” is Jackson, but he doesn’t set out alone. From co-screenwriters and producers to special-effects masters and illustrators, those in the fellowship he assembled matched his enthusiasm for the years it took to complete the trilogy. Nathan wisely explores and celebrates their unique contributions, not just those of actors Elijah Wood, Viggo Mortensen and other more easily identifiable participants. A chapter on movie music master Howard Shore is particularly welcome for explaining the usually overlooked composition of film scores.

Nathan also takes a Helm’s Deep dive into the films’ best creations, their characters as well as their sequences. The wretched creature Gollum became perhaps the first truly realistic CGI character in the movies, thanks to actor Andy Serkis’ voice and motion-capture performance and the army of artists that created nearly 700 sculpted expressions and some 9,000 muscle shapes to bring Gollum to life.

In this age of the director’s extended cut, a flagging reader could be excused for wishing for a downsized edition of “Anything You Can Imagine.” Yet there is much to learn, to chuckle over and to admire as Jackson and his band of indefatigable Kiwis face down the naysayers.

–––

Douglass K. Daniel is the author of “Anne Bancroft: A Life” (University Press of Kentucky).