Is it simply a sign of memory impairment, or are there benefits? (Pexels Photo)

By Sven Vanneste, Trinity College Dublin and Elva Arulchelvan, Trinity College Dublin, The Conversation

Forgetting is part of our daily lives. You may walk into a room only to forget why you went in there – or perhaps someone says hi on the street and you can’t remember their name.

But why do we forget things? Is it simply a sign of memory impairment, or are there benefits?

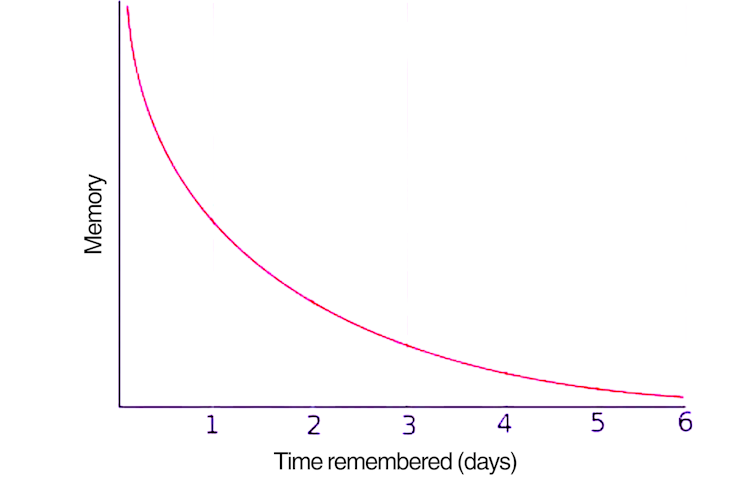

One of the earliest findings in this area highlighted that forgetting can occur simply because the average person’s memories fade away. This comes from 19th century German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, whose “forgetting curve” showed how most people forget the details of new information quite rapidly, but this tapers off over time. More recently, this has been replicated by neuroscientists.

The forgetting curve:

Forgetting can also serve functional purposes, however. Our brains are bombarded with information constantly. If we were to remember every detail, it would become increasingly difficult to retain the important information.

One of the ways that we avoid this is by not paying sufficient attention in the first place. Nobel prize winner Eric Kandel, and a host of subsequent research, suggest that memories are formed when the connections (synapses) between the cells in the brain (the neurons) are strengthened.

Paying attention to something can strengthen those connections and sustain that memory. This same mechanism enables us to forget all the irrelevant details that we encounter each day. So although people show increased signs of being distracted as they age, and memory-related disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease are associated with attention impairments, we all need to be able to forget all the unimportant details in order to create memories.

Handling new information

Recalling a memory can sometimes also lead to it changing for the purposes of coping with new information. Suppose your daily commute involves driving the same route every day. You probably have a strong memory for this route, with the underlying brain connections strengthened by each journey.

But suppose one Monday, one of your usual roads is closed, and there’s a new route for the next three weeks. Your memory for the journey needs to be flexible enough to incorporate this new information. One way in which the brain does this is by weakening some of the memory connections, while strengthening new additional connections to remember the new route.

Clearly, an inability to update our memories would have significant negative consequences. Consider PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), where an inability to update or forget a traumatic memory means an individual is perpetually triggered by reminders in their environment.

From an evolutionary standpoint, forgetting old memories in response to new information is undoubtedly beneficial. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors might have repeatedly visited a safe water hole, only to one day discover a rival settlement, or a bear with newborn cubs there. Their brains had to be able to update the memory to label this location as no longer safe. Failure to do so would have been a threat to their survival.

Reactivating memories

Sometimes, forgetting may not be due to memory loss, but to changes in our ability to access memories. Rodent research has demonstrated how forgotten memories can be remembered (or reactivated) by supporting the synaptic connections mentioned above.

Rodents were taught to associate something neutral (like a bell ringing) with something unpleasant (like a mild shock to the foot). After several repetitions, the rodents formed a “fear memory” where hearing the bell made them react as though they expected a shock. The researchers were able to isolate the neuronal connections which were activated by pairing the bell and the shock, in the part of the brain known as the amygdala.

They then wondered if artificially activating these neurons would make the rodents act as if they expected their foot to be shocked even if there was no bell and no shock. They did this using a technique called optogenetic stimulation, which involves using light and genetic engineering, and showed that it was indeed possible to activate (and subsequently inactivate) such memories.

One way that this might be relevant to humans is through a type of transient forgetting which might not be due to memory loss. Return to the earlier example where you see someone in the street and can’t remember their name. Perhaps you believe you know the first letter, and you’ll get the name in a moment. This is known as the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon.

When this was originally studied by American psychologists Roger Brown and David McNeill in the 1960s, they reported that people’s ability to identify aspects of the missing word was better than chance. This suggested that the information was not fully forgotten.

One theory is that the phenomenon occurs as a result of weakened connections in memory between the words and their meanings, reflecting difficulty in remembering the desired information.

However, another possibility is that the phenomenon might serve as a signal to the individual that the information is not forgotten, only currently inaccessible.

This might explain why it occurs more frequently as people age and become more knowledgeable, meaning their brains have to sort through more information to remember something. The tip of the tongue phenomenon might be their brain’s means of letting them know that the desired information is not forgotten, and that perseverance may lead to successful remembering.

In sum, we may forget information for a host of reasons. Because we weren’t paying attention or because information decays over time. We may forget in order to update memories. And sometimes forgotten information is not permanently lost, but rather inaccessible. All these forms of forgetting help our brain to function efficiently, and have supported our survival over many generations.

This is certainly not to minimise the negative outcomes caused by people becoming very forgetful (for example, through Alzheimer’s disease). Nonetheless, forgetting has its evolutionary advantages. We only hope that you’ve found this article sufficiently interesting that you won’t forget its contents in a hurry.![]()

Sven Vanneste, Professor of Clinical Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin and Elva Arulchelvan, Lecturer in Psychology and PhD Researcher in Psychology and Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.