Until now, long-term fixed-rate mortgages have never caught on in the UK, mainly due to a lack of enthusiasm by banks and building societies. (Pexels Photo)

My generation of baby boomers in the UK generally grew up with reasonable expectations of buying a home in our mid-20s with a 25-year mortgage, happily being able to afford a family, and maybe retiring in our early 60s with a comfortable pension. How different today.

Largely because of an increase in mortgage costs, the percentage of first-time buyers taking out a home loan of between 36 and 40 years has doubled in the last two years, and is more than 400 percentage points higher than in 2008. Across the board, the 36- to 40-year mortgage has risen from roughly 16 in every 100 mortgages to 33 in every 100 over the same period.

Until now, long-term fixed-rate mortgages have never caught on in the UK, mainly due to a lack of enthusiasm by banks and building societies. But there has been an increase in 40-year mortgage loans to make purchases of ever more expensive houses affordable.

As far back as 2004, a report commissioned by the then-chancellor, Gordon Brown, urged lenders “to provide long-term fixed-rate loans” of more than five years. This report noted the popularity of these loans in the US and much of Europe.

Today, a US property buyer can get a 30-year fixed deal at an annual rate of around 6.8%, while a French citizen can access a 25-year loan at about 4.5%.

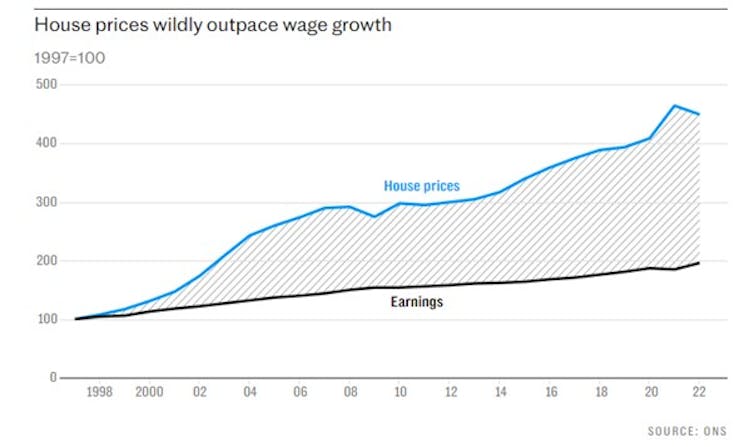

The increasing price of property, both in real terms and in multiples of price-to-average salary, is a major factor. Average house prices are now eight times higher than average earnings, having grown two-and-a-half times faster than salaries (see graph below).

Office for National Statistics

Where will this trend end? Basic economics says that prices are driven by supply and demand. It is almost impossible to miss the news that housebuilding targets in the UK are not being met, and that supply of new homes is a problem.

Also, the demand from buyers shows no signs of easing. So, the millennial children of baby boomers, and the Gen Z-ers that followed them, all have issues that my generation didn’t face.

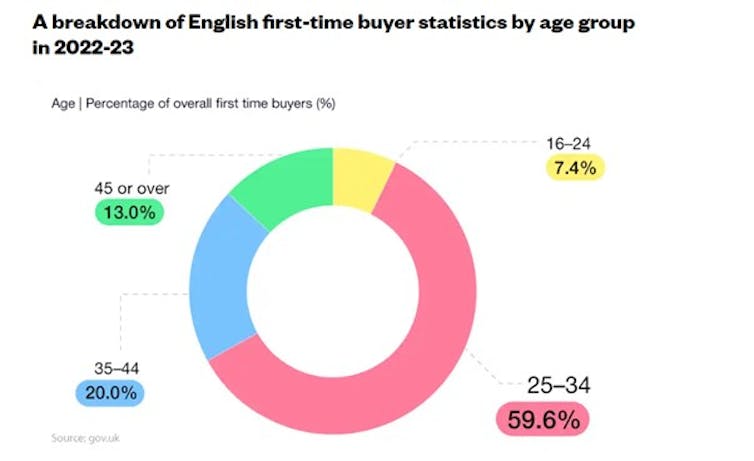

In 2022-23, of the nearly 900,000 “recent” first-time buyers (meaning they had bought within the last three years), 79.6% were between the ages of 25 and 44. Their average mortgage was over £201,000. But the most striking statistic was that 42% of these mortgages have an end date well beyond age 66.

With the increased cost of buying a house coupled with the rising cost of living, it is little surprise that many buyers (not just first-time) are looking to cut costs wherever possible to get on the housing ladder. And for a generation with an enforced 40-year student debt, why would a mortgage of the same length be unpalatable?

But cost is only half the story – the other issue is cash flow.

Can the borrower afford an extra £200-300 per month (on a £250,000 house with a deposit of £50,000) to take on a 25-year mortgage? Or does the saving with a longer-term loan seem irresistible, despite the mortgage being 25-35% more expensive over the full term.

I bought my first home in 1983 for £18,000 with a £3,000 deposit. At that time, an individual on the average UK salary of £16,000 and a 25-year mortgage had mortgage costs at 34% of monthly income.

Graph showing first-time buyers by age group. Uswitch

The 30-39 age group have an average salary of £37,544. The take-home salary obviously depends on tax code, student debt and pension contributions. For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume our first-time buyer has a student loan.

Without paying into a pension, the take-home pay is £2,469 per month, going down to £2,365 with a pension contribution of 5%, and then £2,261 if 10% goes towards a pension. These figures rise by £76 per month if there is no student loan.

So, for a first-time buyer with the minimum 5% invested in their automatically enrolled pension, a 95% mortgage over 25 years is 59% of take-home pay. That’s eye-watering, and that’s when people start thinking about cost savings.

Extending the mortgage to 40 years saves £300 per month which will be very appealing to many cash-strapped buyers. Opting out of the pension might be attractive as well – another saving in the region of £120 per month. These two simple changes improve the first-time buyer’s monthly available cash flow by about £500.

We still appear to be a society in which many people want to own their own castle, but that’s getting harder, and in lots of cases something has to give. This could be a decision about having mortgages into your 70s, or having less children, investing in savings and pensions. Or it could be a combination of all the above.![]()

Chris Parry, Principal Lecturer in Finance, Cardiff Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.