Business and Economy

It’s time to index fuel taxes

The fact remains that since fuel is taxed by volume, the amount collected is proportional to the number of liters of fuel consumed. (Pexels photo)

(Version française disponible ici)

Raising taxes is generally not a way for our political decision-makers to become popular.

This is even more true if these taxes affect a broad base of taxpayers. This is particularly true of fuel taxes in places where per capita consumption is high, as is the case in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada. But even if raising these taxes is difficult, it is nonetheless a rational and coherent policy choice.

In the Canadian provinces, the introduction of fuel taxes started at the beginning of the last century with the arrival of motor vehicles. The introduction of these taxes was justified in part by the cost of road maintenance to the provinces. However, these taxes and the federal excise tax on gasoline and diesel are calculated on volume with no provision for indexation. As a result, their levels have been raised from time to time over the years to enable them to play the role they were intended to play when they were introduced.

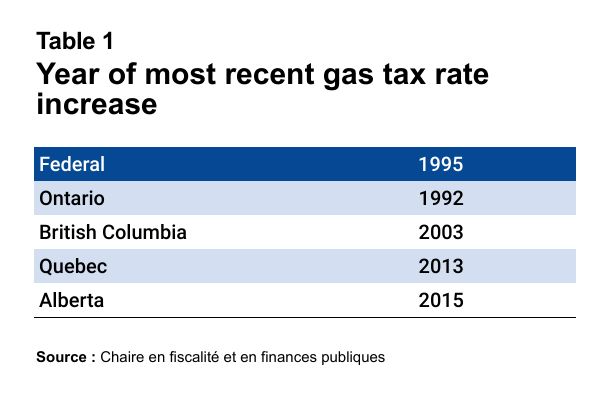

Still, the federal tax rate has remained unchanged since 1995. In Ontario, too, the last rate increase was nearly 30 years ago. In British Columbia, the tax rate was revised some 20 years ago, and about ten years ago in Quebec and Alberta, as Table 1 shows.

Meanwhile, the cost of maintaining the public infrastructure needed to support the use of cars and trucks has continued to rise.

A tax with an impact that melts away

The passage of time reduces both the effects of a volume tax on participants in the economy – including households – and the real value of the revenue generated. Generally speaking, since 1981, fuel tax revenues have been declining in proportion to the size of the economy, as represented by gross domestic product (GDP), as shown in Figure 1.

The weight of the federal excise tax in the Canadian economy has fallen from a high of 0.53 per cent in 1993 to a low of 0.20 per cent in 2021. In Ontario, the drop in the weight of the specific tax has been even more spectacular, from 0.76 per cent in 1992 to 0.25 per cent in 2022, a drop of two-thirds. In Quebec, despite a slight rise between 2010 and 2013 following an increase in the tax rate, its weight is now just 0.37 per cent, even though it has already exceeded 1.4 per cent of GDP. Alberta also saw the weight of the tax in its economy fall, despite a temporary increase in the rate in 2015.

Faced with a similar issue with excise duties on tobacco products and excise duty rates on alcohol products, the federal government recently indexed them.

In the case of tobacco products, an adjustment to the taxes applied per product unit was made in 2018. These prices are indexed annually on April 1st on the basis of the annual change in the consumer price index (CPI) since 2019. In the case of alcoholic products, these duties (which apply by volume, as for fuels) were indexed by 2 per cent on March 23, 2017. They have been automatically adjusted in line with the CPI on April 1st of each year since 2018.

Why not do the same for fuels?

User pay

The user-pay principle states that a user, company or individual must cover the costs associated with their use of a public resource.

It is true that there is no direct link between the level of fuel taxes borne by a road user and the deterioration or pressure they generate on the road network, and the maintenance expenditure and new investments this entails. For example, more efficient motorization makes some vehicles more fuel-efficient, but this does not reduce the cost of maintaining and improving the road network. What’s more, the level of the tax does not necessarily take into account the disproportionate wear and tear caused by heavy vehicles. Taxing gasoline does not make electric vehicle owners contribute to financing roads.

The fact remains that since fuel is taxed by volume, the amount collected is proportional to the number of liters of fuel consumed. This number is in turn proportional to distances covered. There is therefore a proportional relationship between the tax levied and the cost of wear and tear on road infrastructure.

Road maintenance and development is a major expense for provinces. It is desirable that specific taxes be levied in line with the user-pay principle, if only to relay the price signal associated with road infrastructure maintenance and development to those who exert pressure to build roads. Otherwise, the risk is to spread the bill across all taxpayers, regardless of whether or not they make intensive use of the road network.

It was with this in mind that, in 2010, Quebec set up the Fonds des réseaux de transport terrestre (FORT), where most fuel tax revenues have since been allocated. The government’s intention behind the FORT was to reflect the cost of road use, the environmental impact of burning fuel and automobile congestion. The tax was intended to fund both road network improvements and the development of public transit infrastructure.

However, the 2023-2024 Quebec budget projects that FORT will run annual deficits for the next five years – its expenses will reach $8.9 billion in 2027-2028, outstripping revenues by more than $1.7 billion. But in addition, FORT’s revenues are now largely dependent on transfers from the provincial Ministry of Transport, which come from the usual tax levies (income taxes and consumption taxes).

FORT’s funding, previously provided mainly by the fuel tax, now competes with other government missions for money. This situation is a cause for concern in a context where the asset maintenance deficit for the provincial highway network will reach $20.2 billion by 2023, and where funding for public transit poses serious challenges.

A better link between cost and contribution

Indexing specific taxes, as is already the case for other areas of the taxation system, would enable a better match between the costs of maintaining and developing the road network and user contributions.

This logic could also apply to the federal excise tax: the Canadian government funds the Community-Building Fund, which supports local highway, road and bridge projects.

Finally, there are precedents in this area. Indexation of volumetric fuel taxes exists elsewhere, in Sweden, the Netherlands, Australia and 24 American states. It makes sense for Quebec and the rest of the country to follow suit.

This article first appeared on Policy Options and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.