News

Quran burning in Sweden prompts debate on the fine line between freedom of expression and incitement of hatred

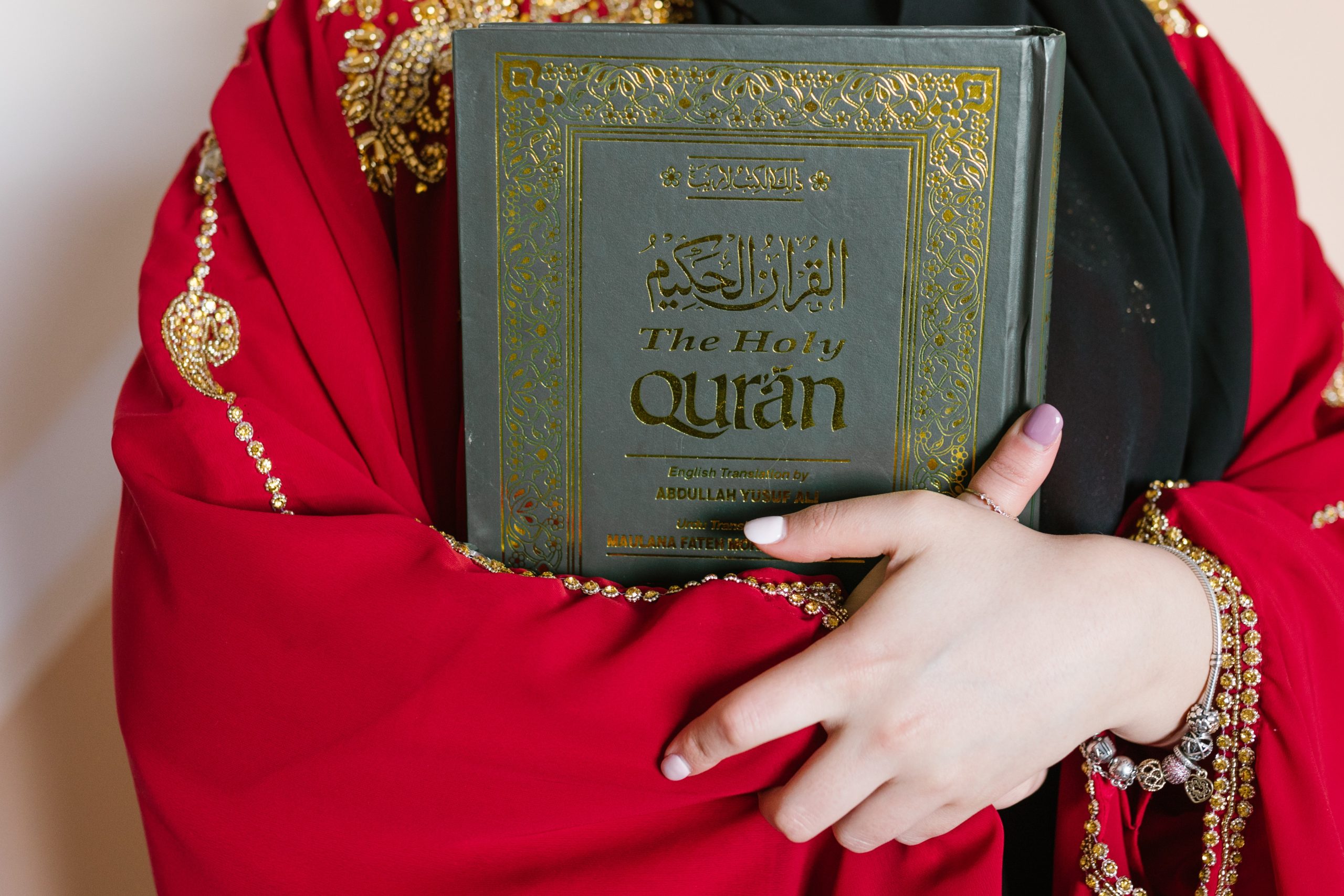

On Aug. 25, Denmark’s government said it would “criminalize” desecration of religious objects and moved a bill banning the burning of scriptures. (Pexels Photo)

The Swedish government is concerned about national security following several incidents involving the burning of the Quran that have provoked demonstrations and outrage from Muslim-majority countries.

The spate of Quran-burning incidents followed an act of desecration by far-right activist Rasmus Paludan on Jan. 21, 2023, in front of the Turkish embassy in Stockholm. On Aug. 25, Denmark’s government said it would “criminalize” desecration of religious objects and moved a bill banning the burning of scriptures.

While freedom of expression is a fundamental human right in liberal democracies, the right to express one’s opinion can become complex when expressing one’s views clashes with the religious and cultural beliefs of others and when this rhetoric veers into hate speech.

As a scholar of European studies, I’m interested in how modern European societies are trying to navigate the fine line between freedom of expression and the need to prevent incitement of hatred; a few are introducing laws specifically addressing hate speech.

Death penalty for insulting God and church

Since medieval times, because of the dominant role of Christianity in political and cultural life, blasphemy against Christian beliefs in European countries was severely punished.

For instance, the Danish Code from 1683 punished people by cutting off their tongue, head or hands. Similarly, in Britain, both on the main island and in its overseas colonies, blasphemy was punished with executions. In 1636, English Puritan settlers in Massachusetts instituted the penalty of death for blasphemy.

For centuries, blasphemy laws were viewed by religious and civil leaders as safeguards for keeping society orderly and strengthening religious rules and influence. These laws showed how much power and influence religious groups wielded back then.

(E)manccipa-Ment via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

During the Enlightenment, from the 1600s to the 1700s, religious institutions began losing power. Advocating for a strict separation of church and state, France became the first country to repeal its blasphemy law in 1881. Seven other European countries repealed their laws between the 1900s and 2000s, including Sweden and, more recently, Denmark.

European landscape of blasphemy laws

Several countries in Europe retain blasphemy laws, but their approaches are highly varied. Often the laws may not prevent present-day acts like dishonoring of religious texts.

In Russia, legislators introduced a federal law in 2013 criminalizing public insults of religious beliefs. This followed some provocative performances by the Moscow-based feminist protest art group Pussy Riot. One such protest, a “punk prayer,” in a Moscow cathedral in 2012 criticized the close ties between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Putin regime.

Since 1969, the German penal code has forbidden the public slander of religions and worldviews. While Germany rarely enforces this law, in 2006 an anti-Islam activist got a one-year suspended prison sentence for distributing toilet paper with the words “Quran, the Holy Quran” printed on it.

Austria and Switzerland have laws quite similar to Germany’s in this regard. In 2011, a person in Vienna was fined for calling the Islamic prophet Muhammad a pedophile. This case later went up to the European Court of Human Rights, which supported the Viennese court’s decision. The court said that the person wasn’t trying to have a useful discussion but instead just wanted to show that the prophet Muhammad shouldn’t be respected.

Spain, too, takes a strong stance against religious disrespect. Its penal code makes it a crime to publicly belittle religious beliefs, practices or ceremonies in a way that could hurt the feelings of followers. While Spain introduced this law to safeguard Catholic interests, it also covers religious minorities.

Italy, another Catholic-majority country, punishes acts deemed to be disrespectful to religions. Its penal code has been used to punish actions that insult Christianity. For example, in 2017 authorities charged an artist for depicting Jesus with an erect penis.

Contemporary debate

The Quran burnings in Sweden and Denmark, aren’t random – they’re part of a broader agenda of targeting Muslims that’s being pushed by far-right groups across Europe.

In many European countries, lawmakers and others are asking whether these book burnings should be seen as exercises of free expression or more as incitement based on religion.

A few countries are introducing new legislation to curb hate speech against religious communities. For example, in 2006 England got rid of the blasphemy law and introduced The Racial and Religious Hatred Act, which makes it an offense to stir up religious hatred. After repealing its blasphemy law in 2020, Ireland has been discussing the introduction of a hate speech law, which will criminalize any communication or behavior that is likely to incite violence or hatred.

Sweden passed a hate speech law in 1970 protecting racial, ethnic, religious and sexual minorities. Swedish authorities pointed to this legislation when they took action against a Quran-burning incident that occurred in front of a mosque in June 2023.

The police argued that the Quran burning wasn’t just about religion but specifically targeted the Muslim community. This was evident, according to the authorities, as the incident took place in front of a mosque during the Islamic holiday of Eid, setting it apart from other burnings that took place outside of the Swedish Royal Palace, the Turkish and Iraqi embassies and other public spaces. Because of the existing hate speech law focusing on incitement against minorities rather than religions, the activist received a fine from the police.

In recent weeks, some have called for a stricter application of the hate speech law and have demanded a ban on all Quran-burning events for implicitly inciting hatred against Muslims.

A global challenge

This discussion isn’t limited to Europe alone. Even in the U.S., there’s an ongoing debate about the boundaries of free speech. The First Amendment of the Constitution allows free speech, which some can interpret as the right to burn holy books.

Terry Jones, for instance, is a controversial Christian pastor from Florida. He organized Quran-burning events in Gainesville in 2011 and 2012. His only legal consequence was a US$271 fine from Gainesville Fire Rescue for not following fire safety rules.

Following Jones’ announcement that he was going to burn the Quran, President Barack Obama said that the pastor violated U.S. principles of religious tolerance. Legal scholar Jack Balkin recommended using free speech in promoting pluralist values to counter Jones’ hatred. Scholar of law and religion Jane Wise suggested that the U.S. could follow the English example by banning hate speech.

As societies change, I believe it has become important to recognize when freedom of speech has turned into promoting hatred. Figuring out where this boundary lies, understanding the standards applied and uncovering potential biases can spark important conversations. While a solution that applies to every single country may not exist, it’s essential to engage in this dialogue, recognizing its complexity and the varying perspectives across societies.![]()

Armin Langer, Assistant Professor of European Studies, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.