News

Giuliani claims the First Amendment lets him lie – 3 essential reads

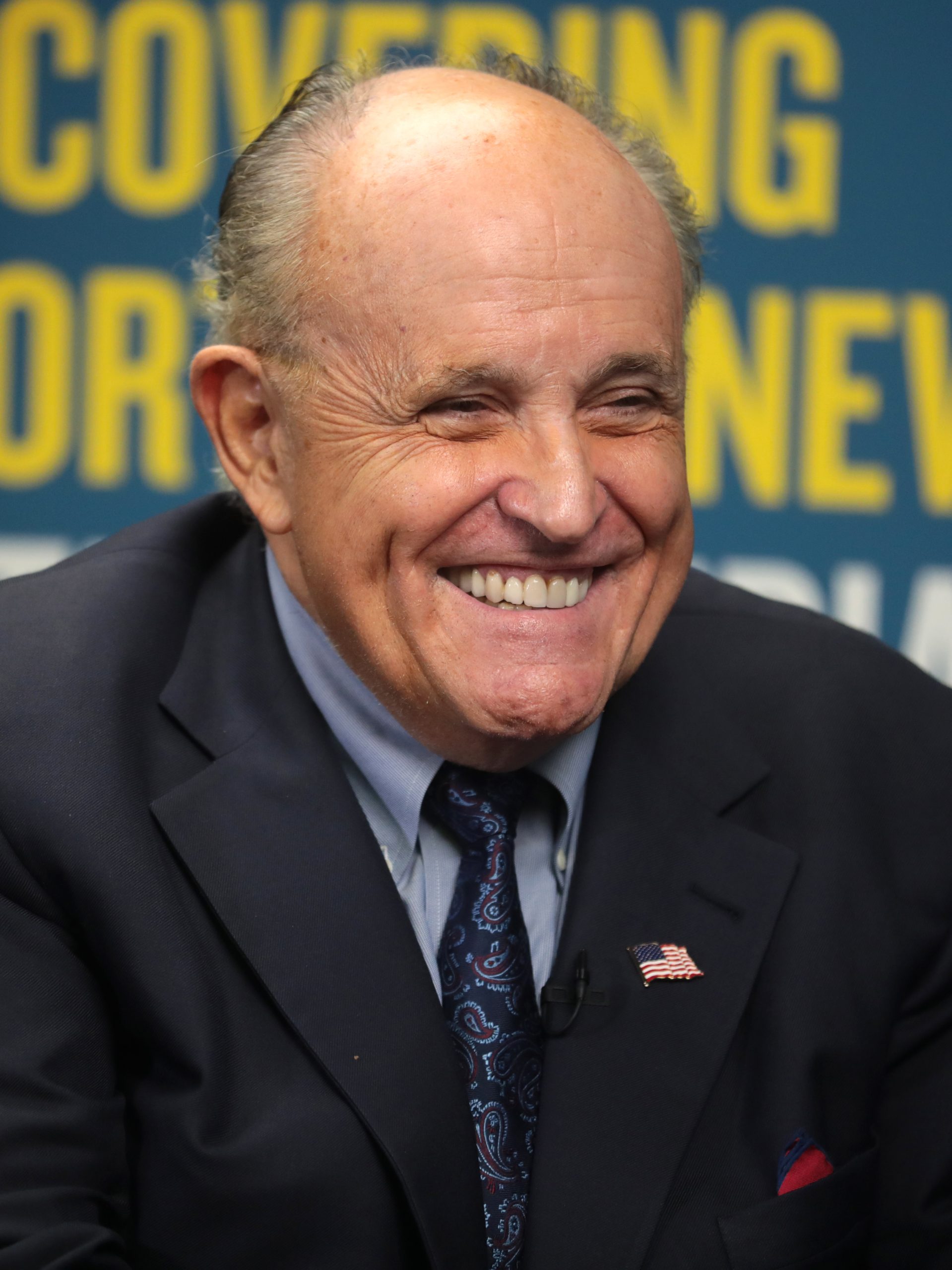

FILE: Former Mayor Rudy Giuliani speaking with the media at the 2019 Student Action Summit hosted by Turning Point USA at the Palm Beach County Convention Center in West Palm Beach, Florida. (Photo By Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In his response to a lawsuit filed by two Georgia election workers who said Rudy Giuliani harmed them by falsely alleging they mishandled ballots in the 2020 presidential election, Giuliani has admitted lying. But he says the women suffered no harm – and claims that his lies are protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The Conversation U.S. has published several articles by scholars explaining what the First Amendment – which, broadly speaking, protects freedom of speech and the press – does and doesn’t say. That includes how it can and can’t be used to protect speech about political controversies, and whether speech that harms or threatens to harm another person is protected. Here is a selection from among those articles.

1. Not all speech is protected

The First Amendment’s protections are not absolute, wrote Lynn Greenky, a communications scholar at Syracuse University.

“When the rights and liberties of others are in serious jeopardy, speakers who provoke others into violence, wrongfully and recklessly injure reputations or incite others to engage in illegal activity may be silenced or punished,” she wrote.

“People whose words cause actual harm to others can be held liable for that damage,” she noted. That’s what the Georgia election workers are claiming in their lawsuit.

Lying about people and bullying them can have consequences despite free-speech protections, Greenky explained: “Right-wing commentator Alex Jones found that out when courts ordered him to pay more than US$1 billion in damages for his statements about, and treatment of, parents of children who were killed in the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut.”

2. Defaming someone can be costly

Jones is not the only defamation defendant who has found lying costly. Dominion Voting Systems sued Fox News for spreading lies about its voting machines in the wake of the 2020 presidential election. Rather than go to trial, Fox settled for $787 million.

But communication scholar Nicole Kraft

at The Ohio State University warned that if the case had gone to trial, proving defamation might have been difficult.

“To be considered defamation, information or claims must be presented as fact and disseminated so others read or see it and must identify the person or business and offer the information with a reckless disregard for the truth,” she wrote.

Another key question, she observed, is the amount of damage the statements do. “Defamation happens when someone publishes or publicly broadcasts falsehoods about a person or a corporation in a way that harms their reputation to the point of damage,” she wrote.

In his recent court filing, Giuliani appears to be saying the election workers weren’t harmed by his statements.

But they are claiming they were harmed, including that they received threats and hateful and racist messages from people in the wake of Giuliani’s allegations.

3. The case could be easier

It’s not clear whether Giuliani has claimed to have been a politician at the time he made the false statements about the Georgia election workers. But he was functioning as a personal attorney and representative of Donald Trump, who is definitely a politician.

Allowing politicians to lie with impunity can be dangerous for democracy, warned Drake University constitutional scholar Miguel Schor:

“The First Amendment was written in an era when government censorship was the principal danger to self-government,” he wrote. “Today, politicians and ordinary citizens can harness new information technologies to spread misinformation and deepen polarization. A weakened news media will fail to police those assertions, or a partisan news media will amplify them.”

Schor found a potential solution in a 2012 opinion by Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, which said laws and courts should be able to penalize not just the harms caused by speech but also “false statements about easily verifiable facts.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.![]()

Jeff Inglis, Freelance Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.