Canada News

What log driving can teach us about forests, past and present

In North America, log driving is thought to have stopped by the end of the 20th century, with the exception of British Columbia, where it is still practised on a small scale. (Pexels Photo)

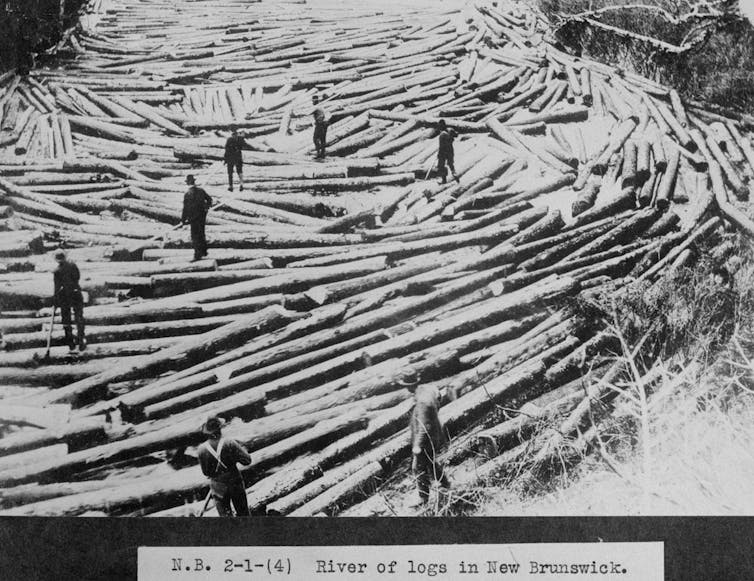

The log drive is an integral part of Québec culture. Specifically, log driving refers to the use of waterways to float and transport logs from harvesting sites to sawmills or ports where they are exported.

This article is part of La Conversation Canada’s series The boreal forest: A thousand secrets, a thousand dangers

La Conversation Canada invites you to take a virtual walk in the heart of the boreal forest. In this series, our experts focus on management and sustainable development issues, natural disturbances, the ecology of terrestrial wildlife and aquatic ecosystems, northern agriculture and the cultural and economic importance of the boreal forest for Indigenous peoples. We hope you have a pleasant — and informative — walk through the forest!

The intensive exploitation of forests in Québec since the time of colonization has resulted in major changes in their structure and dynamics. Few virgin forests remain accessible today, which limits our ability to study pre-industrial forest conditions. Yet this knowledge is essential in order for us to be able to manage forests in a sustainable manner today.

The logs that sank to the bottom of lakes during the log driving period contain information on the history of Québec’s forests to which we have never before had access. For me, as a PhD student in paleoecology and historical ecology at the Groupe de Recherche en Écologie de la MRC Abitibi (GREMA) of the Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT), remnants of log driving represent an unprecedented opportunity to reconstruct the history of pre-industrial forest dynamics and exploitation in Québec.

A practice dating back to the 10th century

Over the past few centuries, logging has played a central role in the economic development of many countries, particularly for the construction of infrastructure and for trade. Forest companies used log driving because it was difficult to get access to roads and railways to transport cut logs.

The logs were cut, put into the water and then guided along the rivers by log drivers. Once logs arrived at the sawmills, they could be stored for several months on the surface of the lakes before being removed for their different uses.

Log driving is thought to have originated in the 10th century in Spain and then spread across Europe over the centuries. It only appeared in Scandinavia and Russia in the 19th century. It began in North America around the same time, most notably in Québec, where it spread to all regions. Log driving in North America is believed to have stopped by the end of the 20th century, except in British Columbia, where it is still practised on a small scale.

Québec forests today

During the period of colonization in Québec (1800-1950), the low transportation costs of log driving made it possible for forestry companies to exploit the forests intensively. This resulted in significant changes to forest ecosystems both in their structure and dynamics.

Library and Archives Canada / PA-165128

The selective logging of the 19th century, which mainly targeted conifers, led to serious changes in the composition of the forests. The forests changed from being dominated by coniferous to deciduous trees. In terms of fire regime change, since hardwoods are less flammable than conifers, there has been a major decrease in fires in Québec forests since colonization. These changes in forest composition and dynamics have resulted in decreased forest resilience. In other words, the ability of forests to return to their initial state after a disturbance is now compromised.

In the context of climate change, this loss of resilience is worrisome, since forests are likely to be subjected to unprecedented conditions. In order to predict how forests might be modified in the future, we have to study how they responded to climate change in the past.

This type of study can be done through dendrochronology, which is the study of tree ring formation. However, in Québec, dendrochronological studies, as well as our knowledge of pre-industrial forests are limited by the young age of the trees, which are rarely older than 200 years. So we need to develop new ways to discover the hidden secrets of our forests in the past.

Travelling back in time with the remains of log driving

At the time of log driving, approximately 15 per cent of the logs transported on waterways were lost in the bottom of lakes and rivers. For example, in the Mauricie region alone, this represents more than 13 million cubic metres of wood. Anoxic conditions (absence of oxygen), the lack of light and cool temperatures (5°C) have ensured that this wood is still well preserved today. Consequently, this wood from the pre-industrial forest represents a unique opportunity to study the past of our forests.

Among other things, the characteristics of these logs (species, diameter, number of growth rings) tell us about the characteristics of pre-industrial forests and the cutting criteria of the time. The passage of a fire also leaves scars on surviving trees. It is possible to date these scars by dendrochronology and to reconstruct the natural fire regime in the pre-industrial era.

Finally, by analyzing the stable isotopes found in the growth rings of logs, we can reconstruct the climate of the past. This will allow us to determine how the climate influenced fires in the past, and to predict how this disturbance might be modified in the future due to climate change. Indeed, there is currently no consensus on studies that attempt to predict how the fire regime might be altered in the context of climate change. More studies on this subject are needed.

Our research project will provide new knowledge about pre-industrial forests and how they have responded to climate change in the past, which will help guide practices for sustainable forest management.![]()

Julie-Pascale Labrecque-Foy, Étudiante au doctorat en paléoécologie et écologie historique, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT) and Miguel Montoro Girona, Professeur d’écologie forestière, Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.