Canada News

With COVID, flu and RSV circulating, it’s time to follow the evidence: Return to mask mandates

Wearing a mask to prevent infected particles from reaching the environment is basic pollution management: control is best at the source. (Pexels photo)

The number of children and babies with respiratory illnesses currently exceeds the capacity of our health system to care for them. More adult Canadians will die directly of COVID-19 this year than died last year or in 2020.

Eight per cent of vaccinated people with COVID infections that don’t require hospitalization end up with long COVID, with each subsequent infection repeating the risk. COVID increases the risk of cardiovascular and other health problems, enough to cause a stark rise in excess deaths and to shorten life expectancy.

In 2020, when adult intensive care units were at risk of being overwhelmed, we wore masks and accepted restrictions. With pediatric intensive care now at risk, will leaders follow the evidence and tell us to mask up? While federal officials and several provinces are now recommending masks in all indoor public settings — although Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health Kieran Moore was seen without one at a party — there are no returns to mandates for the public yet.

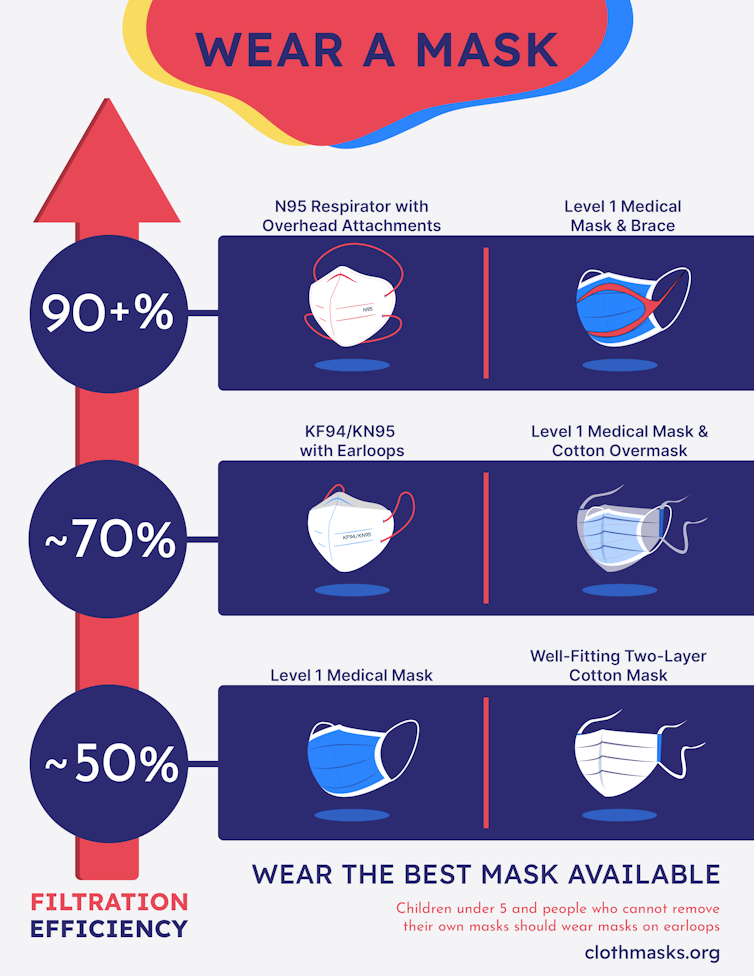

Wear the best mask available

We now know that masks prevent the spread of respiratory diseases; some better than others.

(Gurleen Dulai, Ranmeet Dulai), Author provided

The most effective masks, and the only ones recognized as respiratory protection by formal standards, are respirator masks: N95s, CaN99s, FFP3s and reusable elastomeric respirators. In workplaces, respirators are fit-tested to the individual, resulting in greater than 99 per cent protection.

Even without fit testing, respirator masks prevent more than 90 per cent of particles smaller than one micron from reaching the wearer (submicron particles, the smallest among those thought to be relevant).

Respirator masks are relatively expensive — typically a few dollars each — but thanks to Canadian manufacturers, they are available and there are no longer concerns about supply chains for front-line workers. They can be safely reused, with good retention of their filtration. New designs are comfortable and fit most faces.

(Gurleen Dulai, Ranmeet Dulai), Author provided

N95s are secured with overhead attachments, providing a good seal at the edges. KN95s and KF94s have excellent filtration material, but their ear loops do not provide as secure a seal, and their filtration is around 70 per cent. A certified medical mask with a well-fitted cloth mask over it, preferably with overhead ties, provides comparable filtration at lower cost.

(Gurleen Dulai, Ranmeet Dulai), Author provided

Certified Level 1 medical masks alone do not fit well, which affects their filtration ability because unfiltered air passes around the edges with every breath. In tests on humans, these have typically filtered at around 50 per cent, similar to well-designed two-layer cotton cloth masks, ideally with overhead ties; both are around 50 per cent.

Poorly fitting cloth masks and non-certified procedure masks are likely worse than 50 per cent, but better than nothing. The World Health Organization advises: “Make wearing a mask a normal part of being around other people,” to which we would add: wear the best mask available.

(Gurleen Dulai, Ranmeet Dulai), Author provided

The filtration data above are mirrored by epidemiologic data showing that protection correlates with mask type. In studies of source control (prevention of contamination of the air by respiratory particles), the same hierarchy of efficiency is seen, with N95s at the top. N95s with exhalation valves are an exception and should not be used to prevent spread of respiratory diseases.

Masks protect against COVID-19 and other respiratory infections. They are also an ideal tool to counter COVID variants, as well as RSV and influenza. Working on basic physical principles — impaction, sedimentation and diffusion — they protect regardless of the variant or strain.

Staying home when sick is helpful, but many people are infectious before they have symptoms, or never have symptoms. Wearing a mask to prevent infected particles from reaching the environment is basic pollution management: control is best at the source.

Wearing a mask to protect the individual, once controversial, is now settled by filtration science and epidemiology. The impact of mask mandates in countries where spontaneous mask wearing was low was repeatedly demonstrated, proving that masks protect us all.

Why people aren’t wearing masks

Why aren’t people wearing masks? Some remember the inconsistency of the advice early in the pandemic. Masks may be conflated with closures and capacity restrictions and the resulting hardships. Whatever the reason — stigma, peer pressure or concern about virtue signalling — countries outside Asia do not have a mask-wearing culture.

(Shiblul Hasan), Author provided

Under these circumstances, it will likely take more than strong recommendations to achieve the high uptake of mask use that will be most effective in reducing transmission of respiratory viruses. Masks protect individuals, imperfectly. Mask mandates (or high voluntary use of masks) protect populations.

Bringing back mask mandates with unequivocal signalling from governments about the effectiveness of both masks and mask mandates would be the best immediate response to our current crisis. Confidence that mask-wearing is effective correlates geographically with willingness to wear a mask: in time, we hope knowledge will change culture. Strong communication from political and public health leadership would increase community understanding that the minor inconvenience of wearing a mask in public indoor spaces is justified by the death and disability prevented.

In North America, the strategy of using masks according to personal judgment has predictably failed, the strategy of strongly recommending masks is unproven, and it’s too late to experiment. Mask mandates, however, are backed by strong evidence of effectiveness in both Canada and the United States.

Mask mandates are less damaging to a recovering economy than physical distancing and capacity limits, and less damaging to learning than a return to remote schooling.

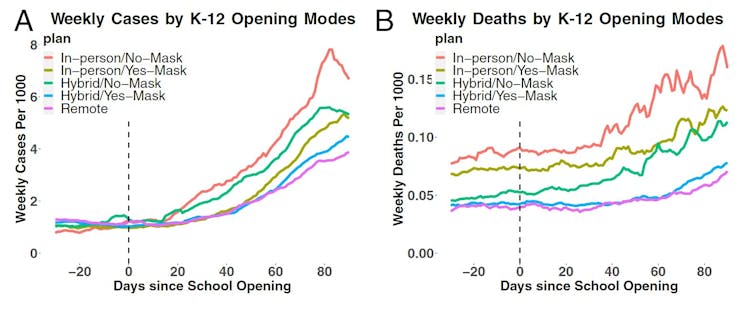

(Chernozhukov et al, PNAS 2021:118;e2103420118), CC BY

Schools and universities represent a particularly important opportunity. COVID spreads between children in schools to infect the whole population; this is mitigated by mask wearing. After Massachusetts lifted its mask mandate, school boards did so at different times, creating a natural experiment: transmission was higher among students and staff where mandates were lifted compared with where they were still in place.

There is no convincing evidence to date that masks reduce social or language skills. Decreasing spread in schools would increase learning by reducing student and teacher sick days and preserving in-person instruction. Keeping children in schools keeps parents at work.

Mask mandates will not produce a rapid fix of our current problems with respiratory viruses. Indicators will lag by weeks. Until we have a whole-of-society approach that recognizes that COVID is airborne, mask mandates offer us the best immediate opportunity to preserve our health-care system, mitigate death and disability from respiratory viruses, support the economy and safely maintain social contacts in our private lives.

Rebecca Rudman, co-founder of the Windsor Essex Sewing Force and member of McMaster’s Cloth Mask Knowledge Exchange, co-authored this article.![]()

Catherine Clase, Professor of Medicine, Epidemiologist, Physician, McMaster University; Charles-Francois de Lannoy, Associate Professor, Chemical Engineering, McMaster University, and Ken G. Drouillard, Professor, Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, School of the Environment, University of Windsor

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.