News

Four more years? Joe Biden and other Democratic hopefuls for the 2024 presidential nomination

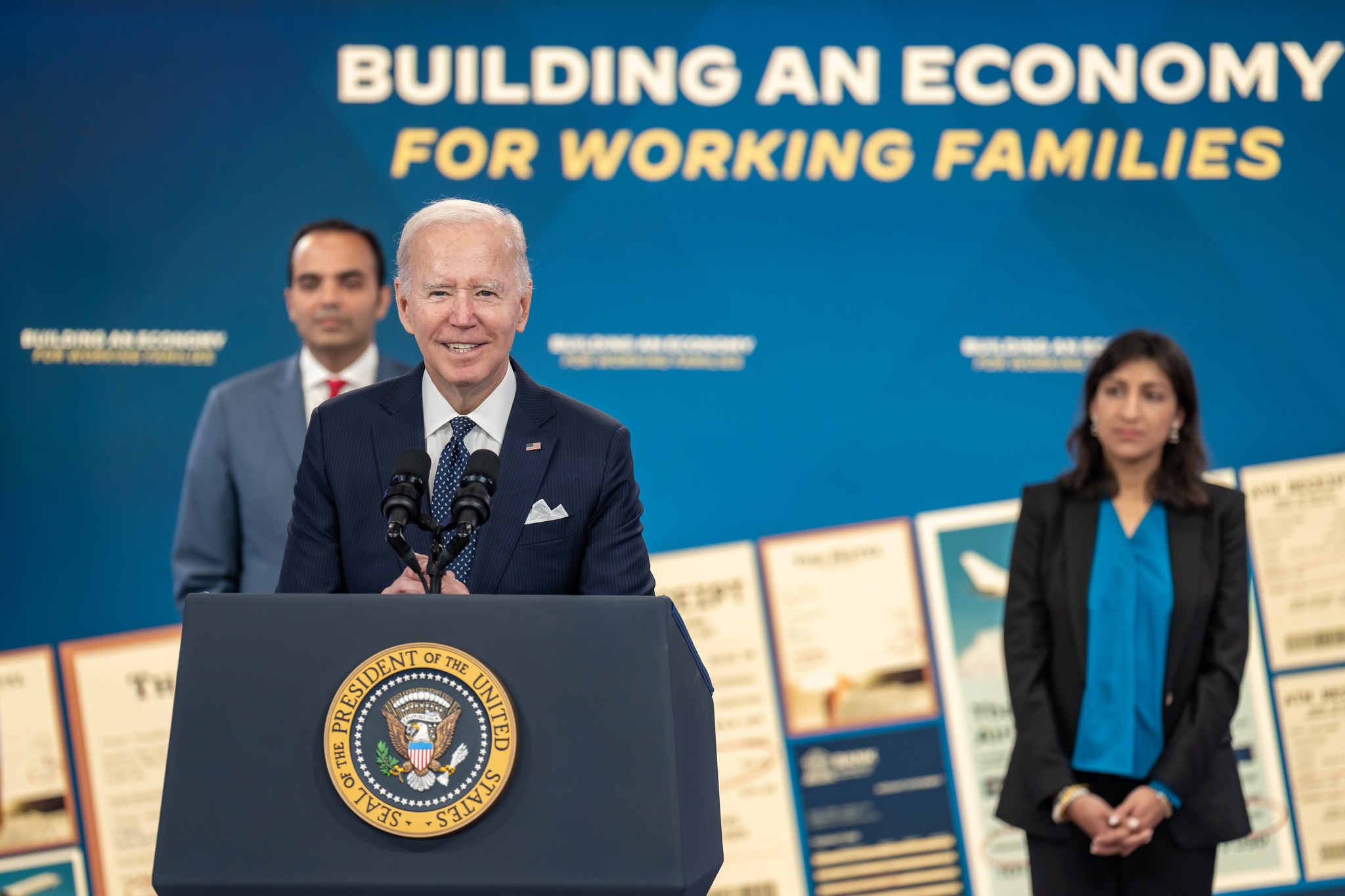

FILE: US President Joe Biden. (Photo: The White House/Facebook)

If US president Joe Biden was looking for an excuse not to run in 2024, he didn’t get it in the midterms. Democrats not only avoided the dreaded “red wave”, but also managed to retain control of the Senate, held Republicans to a razor-thin majority in the House, and swept key gubernatorial contests.

Despite once-in-a-generation inflation and Biden’s stubbornly low approval ratings, Democrats defied expectations and enjoyed the best midterms of any president’s party in decades.

Biden’s victory lap was made even sweeter by the defeat of the most high-profile Trump-supporting candidates, sparking widespread criticism of the former president from within conservative circles.

Nevertheless, Trump has announced his 2024 presidential bid as planned, officially launching the next election cycle on November 15 and throwing down the gauntlet to Biden – who has styled himself as the only candidate who can beat Trump.

What does all this mean for Biden? Will he – and should he – seek reelection?

Murmurs that Biden should step aside in 2024 have gone quiet for the time being. But don’t expect that to last. Two-thirds of voters indicated in exit polls that they prefer Biden not to run for reelection. Those voters included over 40% of Democrats, leaving many on the left grumbling that victories happened in spite of Biden not because of him.

Yet even if Biden’s approval ratings get a bounce, he can’t change his age. Biden, who turns 80 this month, is already the oldest president in America’s history, and his second term would take him to 86. Biden insists that he’s in fine shape. But voters may have other thoughts, especially given several recent flubs that seem to go beyond his usual penchant for gaffes.

Unsurprisingly, Biden has so far indicated that he will run in 2024, with a firm decision expected in early 2023. That sets up at least several months of Democrat introspection, guessing games and hypotheticals on who’s best positioned to lead the party. Although a direct challenge to Biden is unlikely, if he does opt to bow out, the contest for his successor would be a wide open field.

Here are Democrats most likely to vie for the nomination:

Kamala Harris

As vice president, Kamala Harris should be the clear heir apparent to Biden. While still a potential front-runner, Harris would need a serious rebrand to clinch the nomination. Harris’s approval ratings are even worse than Biden’s and many Democrats perceive her nomination as “party suicide,” especially against a potential Republican juggernaut like Trump or rising star Ron DeSantis.

As the first woman and person of colour to rise to the VP office, Harris would also be a barrier-breaking president. Yet even in a Democratic party eager to diversify, Harris may lack the political acumen and appeal to win over a general electorate. The fact that Biden has filled her governing portfolio with low-priority, low-visibility agenda items won’t help her cause — and neither will her own reputation for gaffes.

Pete Buttigieg

A Harvard graduate and former McKinsey consultant who speaks eight languages, Pete Buttigieg, the former small-town mayor of South Bend, Indiana, came to national prominence during the 2020 presidential campaign. He’s since been a notably visible secretary of transportation, promoting Biden’s 2022 infrastructure bill around the country. An openly gay husband and father, Buttigieg would bring a different kind of diversity to the Democratic ticket, even as he struggled to win over crucial black voters in 2020.

Buttigieg’s erudite, wonkish reputation plays well within a demographic eager for a president with policy chops. At just 40 years old, he also resonates with a younger, urban, educated voter, though it’s unclear how he’d fare with other swaths of the electorate.

Nevertheless, Buttigieg was reportedly one of the most sought-after “surrogates” for Democrats campaigning in 2022. And, with several years of Washington service under his belt, Buttigieg may be better poised to parry criticism in this cycle that he lacks requisite governing experience.

Gretchen Whitmer

After holding onto the governorship in the swing state of Michigan with a double-digit win over a Trump-supporting candidate, Gretchen Whitmer’s stature within the Democratic party has continued to rise. A vocal advocate for abortion rights, she has also been one of the most visible Democrats confronting right-wing extremism. At the same time, Whitmer has managed to dodge the death knell label of “coastal elite,” and has leaned into her nickname, “Big Gretch.”

Whitmer has little experience on the national stage, and she’s far from a household name. But she was reportedly shortlisted for Biden’s vice-presidential pick in 2020, and would likely appeal to electorates in critical “rust-belt” states in the midwest. But Whitmer did take considerable heat for her heavy-handed management of the COVID-19 pandemic, triggering outrage – and not just among Republicans.

Gavin Newsom

California governor Gavin Newsom had his own brush with pandemic politics, but survived a recall election in his home state by a wide margin in 2021. Newsom, who cut his teeth in business before pivoting to politics, has long been thought to harbour presidential ambitions. Formerly California’s lieutenant governor and San Francisco’s mayor, Newsom has a CV that, on paper, looks ready for prime-time.

An alleged strike against Newsom is that he’s too smooth and too “Hollywood.” As leader of California, a solidly “blue” or Democrat-voting state, he also doesn’t bring much to the national electoral math. Still, Newsom is positioned to raise his profile over the next year, with US$24 million (£20 million) in a campaign war chest and the political prominence that comes with running one of the biggest states in the country.

Amy Klobuchar

Amy Klobuchar, the senior US senator from Minnesota, won plaudits in the 2020 Democratic primaries for her pragmatic approach to politics. Rated as the “most effective” Democratic senator by a recent Vanderbilt University study, Klobuchar doesn’t dazzle in the traditional sense – and may even be seen as boring. Yet she’s earned a reputation for leadership, chairing both the Senate rules committee and the judiciary subcommittee on competition policy, antitrust, and consumer rights.

Klobuchar won’t be many Democrats’ first pick for president, even if one of her favourite lines in 2020 was that she’d never lost a campaign in her life (that streak ended when she withdrew from the nomination race, giving her support to Biden). Still, in a Democratic field without a clear frontrunner, Klobuchar — who has largely avoided big political missteps (although has been marred by accusations of mistreating her staff) – could become a viable candidate simply by process of elimination.

Bernie Sanders

At 81 years old, Bernie Sanders doesn’t exactly solve the Biden age problem. Although swapping out one octogenarian candidate for another might not seem viable, it’s hardly an impossibility. Sanders, a big-government liberal who identifies as a “democratic socialist”, not only has a cult following among his famed “Bernie Bros.” He also has the most crossover appeal to former Trump voters.

Sanders, who ran for president in both 2016 and 2020, has spent a lifetime championing efforts to tackle inequality through expanded entitlements. While a “last hurrah” run by Sanders might be more about making a point than winning, his celebrity is hard to discount. If Sanders chooses not to run, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is the most likely successors to carry his mantle, while Senator Elizabeth Warren may also consider another run.

All moves now depend on Biden. He has said before that he would “not be disappointed” to face Trump in a rematch, and his recent response to critics who don’t want him to run was: “watch me”. For now, that leaves other presidential hopefuls – and the Democrats’ base – watching, and waiting.![]()

Julie M Norman, Associate Professor in Politics & International Relations & Co-Director of the Centre on US Politics, UCL and Thomas Gift, Associate Professor and Director of the Centre on US Politics, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.