Entertainment

The finale of Better Call Saul: A psychologist explains how Jimmy McGill became Saul Goodman

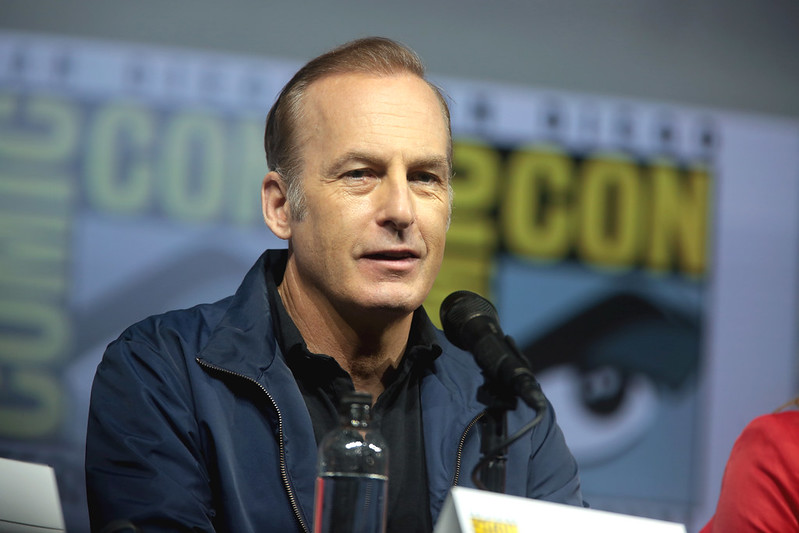

FILE: Bob Odenkirk speaking at the 2018 San Diego Comic Con International, for “Better Call Saul”, at the San Diego Convention Center in San Diego, California. (Photo: Gage Skidmore/Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

This story contains spoilers about ‘Better Call Saul,’ although it doesn’t reveal details of the series finale.

Better Call Saul has wrapped up after six seasons, bringing an end to one of the most interesting characters in the history of television.

Bob Odenkirk’s portrayal of the “criminal lawyer” Saul Goodman began in 2009 during Breaking Bad, but Better Call Saul tells the complex story of the character both before and after the events of Breaking Bad.

As a clinical neuropsychologist and associate professor of psychology — and a fan of Better Call Saul — it’s been fascinating to watch the progression of the character who transforms into three different identities. He goes from young lawyer Jimmy McGill to the corrupt Saul Goodman and then finally to Gene Takovic, the persona he adopts to avoid the law after the events of Breaking Bad.

Jimmy McGill’s character defies categories, capturing the complexity of personal development shaped by circumstances and personal choices.

Antisocial personality disorder

Despite displaying several features of antisocial personality disorder (stealing from his family, a history of conning people and defying authority), he can be compassionate and is guided by an idiosyncratic code of ethics. Sometimes he even exceeds normative morality to the point of altruism (like when he saves the twins’ lives from Tuco’s revenge in Season 1, how he takes exceptionally good care of his brother Chuck during his illness and how he risks his career to save his assistant Huell from jail).

The arc of his character is carefully constructed to resist moralizing. Just as we start to make up our minds about Jimmy, a new side of him is revealed that’s incompatible with that judgment.

The early part of the series tells the story of Jimmy becoming a lawyer after years of pulling small-time cons as “Slippin’ Jimmy.”

While supervisors at his first law firm acknowledge Jimmy’s valuable skill sets (a natural ability to connect with people, highly persuasive, creative problem-solver who holds up under pressure, extremely hard worker), they are constantly on the edge, bracing themselves for the next fallout.

At work, he is a strange mix of assets and liabilities: he generates a multi-million dollar class-action lawsuit for his firm, but his obnoxious, authority-busting behaviour quickly builds up to a critical mass that bosses cannot tolerate.

A magnetic personality

People close to him are drawn to his magnetic personality and are able to see “the good in him.” He makes friends easily, and typically keeps them for life. With her last breath, his mother calls out for Jimmy — as Chuck is dutifully sitting by her deathbed. Davis and Main welcome him to their law firm with open arms. Even the battle-hardened, fish-eyed private investigator Mike Ehrmantraut (whose life trajectory provides a subtle road map to Jimmy’s) has a growing respect for him.

However, they inevitably fall victims of his impulsive need for subversive behaviour. Even so, his vibe is intoxicating. Kim Wexler, who goes from fellow lawyer to co-conspirator to his wife, gets addicted to the thrill of recreational or utilitarian rule-breaking binges he inspires.

Jimmy has a pathological need to challenge the power structure. His thrill-seeking streak gets him in trouble time and again, hurting his loved ones either directly (like when he needs to be bailed out of jail) or indirectly (his limited income due to a suspended law licence, lost trust from deep, dark secrets). Despite his reflex to externalize, deep down he knows Kim is right (“You are always down, Jimmy”), eliciting cycles of self-reflection, depression and eventual recovery.

Jimmy’s personal responsibility for his misfortunes is another fascinating thread. Early on, the balance (an overused symbol of justice in the series) seems to tip toward “his own worst enemy.”

Learned helplessness

As we learn more about Jimmy’s understated but ongoing victimization (gut-wrenching, repeated emotional betrayal by his brother, the arbitrary denial of his application by the law licensing board during the one time he did not try to manipulate the system, his accidental entanglement with the cartel, barely getting paid for his high-quality defender work), an alternative explanation is emerging: a condition known as learned helplessness.

As Jimmy tries hard (though arguably not hard enough) to leave his checkered past behind, he is constantly confronted by the rejection of the system that he openly despises but secretly wants to join.

As his emotional scar tissue accumulates, it turns into callouses. He spends a lot of time in a dissociative reflection, and finally accepts his fate as an eternal misfit. Jimmy slowly becomes (or regresses into?) a street-wise, no-nonsense, tough-minded hustler who is well-connected to the underworld.

As he finds himself on the other side of the law, he develops a new persona: the criminal lawyer Saul Goodman. Identity change is often catalyzed by trauma — in his case, coming to terms with his losses. He is the last McGill left and his unique skill sets cannot be monetized in the legitimate world.

He disappointed his brother (the only man whose approval he craved), his girlfriend, the top lawyers in the state and ultimately, himself. Ushering Chuck toward his suicide may have settled their rivalry in his favour, but it’s also the first of many red lines to cross on his way to Goodmanhood.

Becoming Saul

Becoming Saul is more than taking on a new professional identity: it’s a desperate attempt to reinvent himself and become successful his way through a grotesque fusion of Slippin’ Jimmy (the freedom to be himself) and Charles McGill (the respect he craves).

It may seem like a dramatic transformation, but at some level he simply returns to his roots – this time, as a major-league scam artist embedded within the legal system (that criminal lawyer that Jesse in Breaking Bad references).

The name he chooses (“S’all good, man”) encapsulates the tension that holds his character together: a desire to be liked against an opportunistic appropriation of a culture by portraying himself as a Jewish lawyer.

Personal purgatory

In the words of Tony Soprano, a criminal career ends in one of two ways: jail or death. While Jimmy repeatedly escapes both, the black-and-white footage of his post-Saul life (as Gene Takovic) is an intrusive reminder that his troubles are not over. He’s spending his last years in his own personal purgatory, perpetually re-examining where he went wrong.

Jimmy would make a tough patient if he ever stumbled into a psychologist’s office.

Cognitive therapy (“mind over mood”) has little to offer him in the way of life-changing revelations: he already knows himself pretty well and understands how his self-defeating thought pattern contributes to his problems.

Jimmy could talk circles around a psycho-dynamically oriented clinician, and the authoritarian style of Freudian therapy would likely trigger oppositional behaviour, recapitulating rather than resolving his core conflicts.

He may respond best to Existential or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Although his diagnosis is famously treatment-resistant, the “good in this man” provides a window for a genuine (patient-initiated) attempt at self-redemption in the hands of a highly skilled clinician.

Reminiscent of ancient Greek tragedies in which the heroes rebel against their fate and inevitably lose, Jimmy is a morally ambiguous figure who fights another invisible force — his own impulses that keep him from becoming the man he wants to be.

This is what makes him relatable. We’ve all experienced that struggle.![]()

Laszlo Erdodi, Associate Professor, Psychology, University of Windsor

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.