News

Russia’s rouble is now stronger than before the war – western sanctions are partly to blame

FILE: President of Russia Vladimir Putin during a meeting (Photo by Kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0)

In the days after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 and the west imposed sanctions, the rouble collapsed. The number of roubles to one US dollar quickly fell from about 78 to 138 – a huge move in the world of forex (foreign exchange), and terrifying for those with their wealth in the Russian currency.

Since then, sanctions have tightened and the war shows no signs of reaching an end, but something unexpected has happened to the rouble. Many commentators had thought it would continue weakening, but instead it is now stronger than when the war began. The US dollar is now worth 57 roubles, the best exchange rate in about four years.

Rouble v US dollar

So why has this happened, and what does it mean for the future?

The pre-war rouble

First the backstory. The exchange rate of any country is determined by capital and trade flows: in other words, what money is moving in and out of the country, and the value of exports compared to imports. For the rouble, trade flows are usually more important because Russia is a major oil exporter.

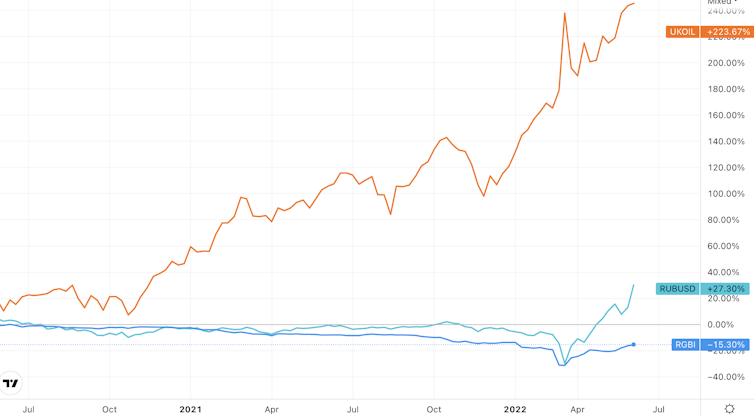

The oil price, as you can see from the chart below, is linked to the rouble – when oil rises, the rouble gets stronger. The price of oil has broadly been climbing since the first half of 2020, which benefited the rouble in the run-up to the war.

Rouble v oil

Trading View

However, the rouble hasn’t risen over that period by as much as it normally would when oil is strong – this is why the two lines on the chart are less in sync since then. This is probably due to changes in capital inflows, specifically over Russian government debt. The share of foreign investors (non-resident holders) in federal loan bonds or OFZs reached a historical maximum of 35% in March 2020, but had declined to 18% before the war.

The reason was changes in tax rules. The interest payments on Russian government bonds for foreign investors were tax-free until a law was passed on March 31 2020 to the effect that they would start paying 30% from January 1 2021. Notice that the rouble started falling as foreign investors began selling their bonds after March 2020.

This explains why the rouble was broadly flat between then and the invasion, in a sign that sales of government bonds more than offset the effect of the strong oil price (you get a sense of this in the chart below, where the bonds are in blue). In short, this bond-selling was a temporary millstone around the rouble that was keeping it lower than it otherwise would have been. Over time, this effect will have reduced, giving the rouble some upward momentum as the oil price remains high.

Rouble v oil and government bonds

Trading View

After the invasion

When the rouble sank to 138 to the US$ in the days after the invasion on February 21, this was its lowest ever level. On February 24, the Central Bank of Russia announced several measures to support the currency.

It banned margin trading, which is when investors borrow money to make much bigger bets in the markets than they can otherwise afford: this meant they couldn’t exacerbate the damage to the rouble by betting heavily that it would fall further. The central bank also used its foreign reserves to buy roubles in the currency markets to help prop up the price. Yet the rouble kept falling, suggesting the moves were not enough.

One reason was a package of western sanctions that were unexpected and arguably the most severe ever imposed, including freezing 60% of Russia’s US$643 billion international reserves on February 27. This package severely limited the Russian central bank’s access to its assets abroad and its ability to bolster the rouble.

The central bank responded on February 28 with a new set of new measures:

- imposing capital controls by banning all transactions with non-residents and all trading of stocks and shares

- a sharp hike in the Russian headline interest rate from 9.5% to 20%

- a US$10,000 (£7,972) limit per month on transfers by residents to bank accounts abroad

- a US$10,000 limit on foreign currency withdrawals

- exporters required to exchange 80% of their foreign exchange earnings within three days.

A month later, President Putin also signed a special decree requiring “unfriendly countries” to pay for Russian gas in roubles.

Explaining the rise

One reason the rouble has strengthened is the restrictions on margin trading and on foreign investors, which has meant that trading volumes have been much lower than usual. The rule forcing exporters to exchange foreign earnings and the partial move to selling gas in roubles have also helped.

Equally, however, other factors unrelated to the Russian central bank have been at play. The oil price has remained strong. Having dipped from a peak just above US$130 per barrel in mid-March to around US$100 a few weeks later, Brent is now at around US$120.

Russia’s imports have also been dampened by the exodus of foreign companies and the western sanctions. This has driven up the current account surplus (the value of exports minus imports) to a historic maximum, which strengthens the currency.

This trade imbalance will probably continue for a while, which may be one reason why Russia has loosened some of the February-March restrictions. The headline interest rate is now back down to 9.5%, the same as when the invasion began. Margin trading is permitted again, the 80% forex rule is gone, residents can now transfer up to US$50,000 per month to foreign bank accounts, and foreigners in “friendly” countries such as China or India are now only restricted to the same extent as Russian residents.

In other words, Russia has cover to move to a more normal financial footing because of the western sanctions. If that sounds like a painful irony, it should be emphasised that the sanctions make it far harder for Russians to spend these relatively strong roubles either on imports or abroad because of travel restrictions.

So although the currency has kept its value, its utility is greatly weakened. Therefore, one might argue that since the sanctions punish Russia, they actually work.![]()

Kirill Shakhnov, Lecturer in Economics, University of Surrey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.