Lifestyle

St. Patrick’s Day: How Irish-born writers contributed to Canadian and Irish histories

For the four million Canadians who have Irish ancestry, St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, is a time to not only celebrate but reflect on how their perception of Irish culture has shaped their identity and lives.

In my book, Canada to Ireland: Poetry, Politics, and the Shaping of Canadian Nationalism, 1788–1900, I examine how Irish-born writers’ historical and literary works shaped narratives and early English-language settler folklore about Canadian identity or life in Canada.

In these years, Irish writers played an important role in transatlantic cultural conversations among British, French and Indigenous nations that influenced Canadian nationalism. Irish migrants and visitors to Canada also affected Irish nationalism through their literary works.

Critical reappraisal

The critical reappraisal of Irish and Canadian cultural relations and influences, as well as Irish encounters with Indigenous Peoples is of current and urgent interest to both Irish and Canadian scholars.

Some Irish Canadians may remember learning in school about Irish-born Thomas D’Arcy McGee (1825-68), the politician who lobbied for protection for the French and Irish — but much less about Irish Canadians like Nicholas Flood Davin whose 1879 report on assimilative industrial schooling for Indigenous Peoples contributed to developing the Indian Residential School System.

St. Patrick’s Day folklore in North America often involves nostalgia for simpler times and may involve recollected cultural and historical wounds.

In this context, and also in the context of the ongoing Indigenous community calls for settlers to be accountable for addressing the harmful legacies of colonialism, it’s relevant to remember, as historian Donald Harmon Akenson notes, that “Irish … settlers and their beneficiaries participated in a system that destroyed or maimed [Indigenous] communities and cultures on a global scale.”

Some Irish-born writers who settled in Canada advocated working with the British in order to gain protections for migrating Irish minorities, or used their storytelling skills to provide solace in ways that advanced settler colonial folklore of being attached to the land.

Other Irish-born writers who visited Canada and encountered Indigenous Peoples returned to Ireland resolute in defending Irish political autonomy and the Irish language against British colonial rule.

Here are five Irish-born 18th- and 19th-century writers to consider.

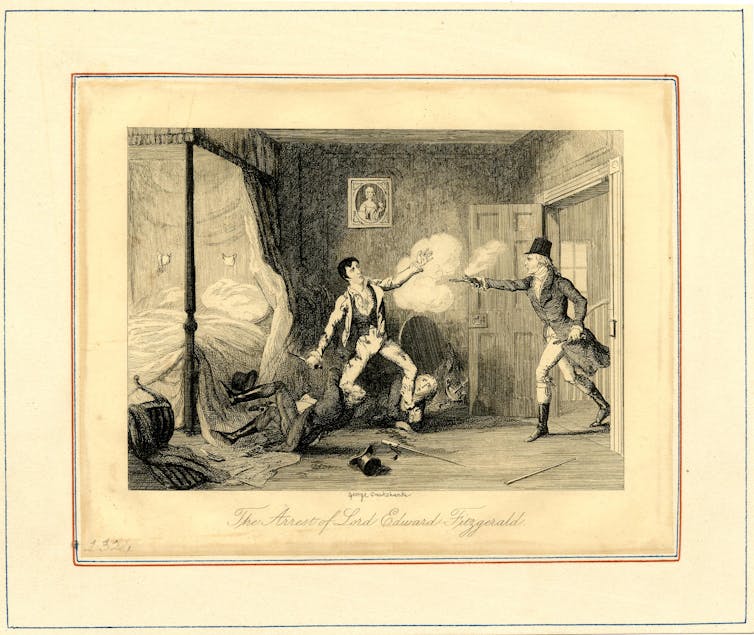

Edward Fitzgerald

Lord Edward Fitzgerald (1763-98) is most known as a leading conspirator in the revolutionary Society of United Irishmen, who planned to overthrow the British in Ireland. His death in a Dublin prison in 1798 after leading the failed rebellion ensured, as historian Daniel Gahan notes, Fitzgerald’s status in Ireland as a “toweringly romantic figure in Irish history.”

But as an officer in the British army, Fitzgerald led an intrepid exploratory voyage from Fredericton to Québec City in winter 1789. Fitzgerald’s letters home describe snowshoeing and canoeing as well as the Indigenous communities that guided and fed him — and likely saved his party’s lives when they got lost. His letters also detail his positive impressions of what he saw as the egalitarian nature of both Indigenous and settler societies.

As I have explored, his descriptions of both snowshoeing and canoeing later popularized in a biography of his life shaped the literary construction of Canadian national identity in the 19th century, including settler-colonial appropriations of canoeing as a Canadian symbol.

Thomas Moore

The Irish patriotic poet Thomas Moore (1779-1852) — Fitzgerald’s biographer —was already a literary celebrity when he arrived in 1804 in Upper and Lower Canada and Nova Scotia as a tourist.

He had travelled in freight canoes piloted by voyageurs for much of his journey from New York to Nova Scotia in 1804 and stopped to visit Niagara Falls and Quebéc City. The lyrics and music for his “Canadian Boat Song” were inspired by the French-Canadian folk ballads that helped the crew keep time and ease their paddling labour. The song would become a popular North American ballad in the 19th century.

The simple and evocative lyric also helped Moore discover the emotional impact created by setting patriotic verses in English to Irish traditional tunes. He put this technique to use in his Irish Melodies, a group of 130 poems set to music. Some of these melodies are still heard or sung at St. Patrick’s Day gatherings today.

After Moore established that the folk ballad tradition could help popularize historical events that would inspire nationalists, the young poets and intellectuals that founded Young Ireland continued to do this in their own cultural (and eventually revolutionary) movement.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee

Thomas D’Arcy McGee, one of Young Ireland’s most gifted poets and historians, fled to North America after the unsuccessful Young Ireland rising of 1848 when the Irish rebelled against the British in British-occupied and famine-ravaged Ireland.

In the famine, about one million Irish died of starvation and related causes. At least one million others fled as refugees. By the 1850s more than 500,000 Irish had immigrated to British North America, including more than 38,000 who landed in Toronto in 1847.

In the view that ballads could help settlers know and appreciate their new home’s past, McGee published Canadian Ballads in 1858. The collection celebrated the heroism of northern explorers as well as Indigenous and French Canadian spirituality and popularized ghost stories.

University of British Columbia historian Margery Fee has examined McGee and Métis leader Louis Riel to explore parallels and differences between how these figures valued the preservation of culture and distinct identity.

McGee, once an anti-British revolutionary, became a “Father of Canadian Confederation,” and also advocated for the Irish agreeing to limited self-government in the British Empire. McGee was viewed as a traitor by some Irish and was assassinated on Sparks Street in Ottawa in 1868.

Charles Dawson Shanly

Dublin-born Charles Dawson Shanly continued the tradition of presenting supernatural events as an essential element of early English-language settler Canadian folklore. His eerie ballad, “The Walker of the Snow,” was published in 1859 and anthologized frequently. Combining Irish and Canadian ballad traditions, it narrates a ghost story told in time to the “harp-twang” of snowshoes.

This ballad became an early country and western recording when it was recorded by American country singer Billie Maxwell in 1929. Through the late singer Sean Tyrell, it has also become a traditional music standard in Ireland.

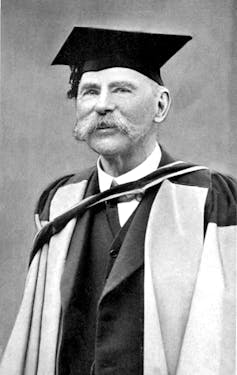

Douglas Hyde

Douglas Hyde, Irish-language poet and scholar, arrived in Fredericton in 1890 to teach languages at University of New Brunswick. During the winter, he took part in a Caribou hunt with his guides, some of them members of the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) People.

The hunting party spent their first night in the cabin of an Irish settler, who to Hyde’s delight conversed with him in Irish. Although it was one of the coldest winters on record, his guides ensured Hyde was able to navigate the deep snows in snowshoes and to sleep comfortably outdoors on a bed made of spruce boughs.

At night, Indigenous guides told stories that reminded Hyde of the oral tradition in Ireland, although the guides relayed that stories lost much depth and meaning in translation in English.

In Ireland, Hyde recounted his experience with the Irish settler and the Wolastoqiyik guides in his cultural manifesto, “The Necessity of De-Anglicizing Ireland.” Here, he argued that the revival of the Irish language was essential if Irish people were to know their own rich culture in all its nuance and complexity.

Hyde helped launch an Irish-language revival of cultural decolonization that Irish nationalists took to its political conclusion when Irish republicans, led by the Irish language teacher and poet Pádraig Pearse, took the first steps towards creating a sovereign nation during the Easter Rising of 1916.

Ireland broke its final link with England in 1938, replacing King George V as head of state — with Douglas Hyde, the first president (Uachtáran) of Ireland.

In Canada, Hyde had seen Irish settlers and Indigenous communities preserve a distinct element of their cultural identity in their language. A memento of his visit was a photo of him wearing a sealskin hat and carrying snowshoes, which he kept in his study for the rest of his life.![]()

Michele Holmgren, Associate Professor of Canadian and Irish literature, Department of English, Languages and Cultures, Mount Royal University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.