Lifestyle

Curious Kids: will time ever stop?

Will time ever stop? – Casandra, aged 11, Epsom, UK

Time began when the universe did. How – and if – the universe ends will determine whether time will end as well.

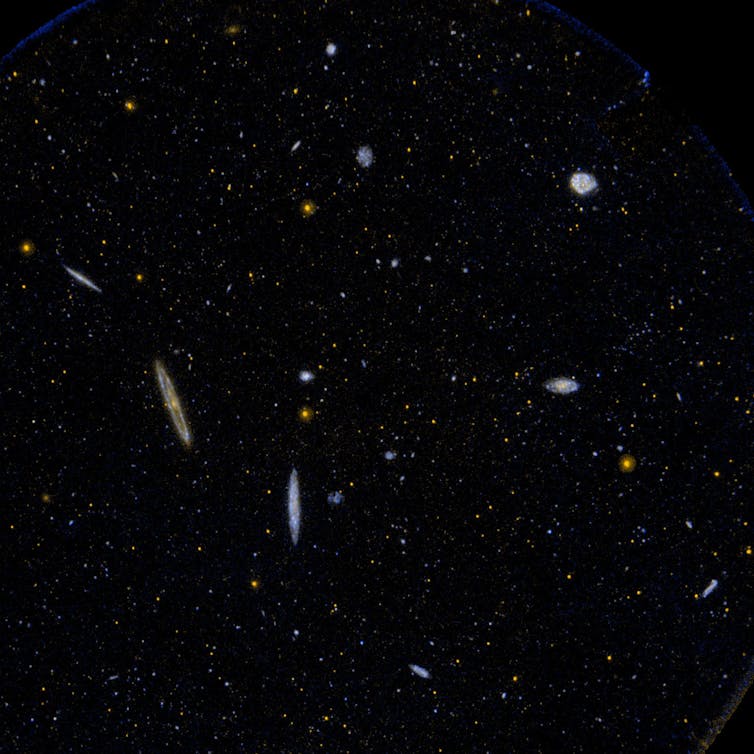

We think the universe started out squeezed into an infinitely small space. For some reason we do not yet understand, the universe immediately started to expand – to get bigger and bigger. This idea, or “model”, of the beginning of the universe is called the Big Bang.

In 1998, scientists learned that the universe is expanding faster and faster, but we still don’t know why this is happening.

Dark energy

It might have something to do with the energy of the vacuum of space. It might be a new type of energy field. Or, it might be some completely new form of physics. To symbolise our lack of understanding, we call this new phenomenon “dark energy”.

Curious Kids is a series by The Conversation that gives children the chance to have their questions about the world answered by experts. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskids@theconversation.com and make sure you include the asker’s first name, age and town or city. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we’ll do our very best.

Even though we are still trying to work out what dark energy is, we can already use it to predict different ways in which the universe might end.

If dark energy is not too strong, it will take an infinite amount of time for the universe to expand to an infinitely large size. Infinite means never-ending, and so in this case, time will never end.

But, if dark energy is too strong, it will cause the universe to expand so fast that everything in it – even the tiny atoms that are the building blocks for every single thing in existence – will be ripped apart. In this Big Rip scenario, the universe will not expand forever.

Instead, it will expand so fast that it will reach an infinitely large size at a specific moment in time. That moment, when the universe is infinitely large and all matter has been ripped apart, will be the last. The universe will cease to exist, and time will come to an end.

There is another way that the universe might end. This is called the Big Crunch. In this scenario, the universe will at some point stop expanding and start shrinking again.

The universe will get smaller and smaller, galaxies will collide with each other, and all the matter in the universe will be scrunched up together. When the universe will once again be squeezed into an infinitely small space, time will end.

The Big Bounce

Some physicists think that a Big Crunch may not be the end of the universe, but merely the middle of its existence. According to this way of thinking, the universe starts out infinitely large, then shrinks for an infinitely long time until it is squeezed into the smallest size possible. When that happens, instead of ending, there is a Big Bang and the universe begins to expand.

In this Big Bounce scenario, there is an infinite amount of time before the universe becomes scrunched up into the smallest possible space, and an infinite amount of time as it expands afterwards. Time has no beginning and no end.

In some Big Bounce models, the universe only bounces once. In others it goes through an infinite number of bounces, constantly expanding and contracting, like an accordion that never stops playing.

All of these scenarios show us what is possible, not necessarily what is true. For one thing, we still need to figure out what dark energy is. More importantly, there is no guarantee that our current understanding of how the universe works is correct.

One day, maybe 100 years or just a few weeks from now, someone (perhaps you?) will come up with a better theory to describe the workings of the universe. Maybe then we will know whether time ever comes to and end. Then again, perhaps the new theory will have a wildly different concept of time, or even do away with it altogether.

Or Graur, Senior Lecturer in Astrophysics, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.