Canada News

Sunwing saga: Why do influencers have so much sway?

The story of a group of Québec influencers enjoying the “party of the year” on board a Sunwing flight in complete defiance of health restrictions made headlines at the beginning of January, not just in Québec and in Canada, but also internationally and, of course, in social media. Even Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called the partiers “idiots.”

I was particularly intrigued by this case, as my doctoral dissertation focuses on the engagement relationship between followers and influencers on social media. How do we explain how the phenomenon became so widespread?

Social media: The home of influencers

With over 4.2 billion users, using social media is the most popular online activity and the most frequently used search tool.

According to a 2021 study by researcher Guyonne Rogier and her colleagues at the faculty of medicine and psychology of Sapienza University in Italy, isolation brought about by the pandemic is increasing people’s dependence on social media.

Mirroring social interactions and personal identity, social media fulfils emotional and information needs, such as obtaining advice or recommendations. Ninty per cent of consumers trust the opinion of a person they consider to be reliable over that of an official media source. Hence the popularity of influencers.

According to my research, an influencer is an opinion leader who is very active on social media, where they share their interests and details about their daily lives with members of their community. An influencer is perceived to be a role model that followers identify with or aspire to be.

The influencer uses their personal brand, their human brand, to relay information, sometimes directing the attitude and behaviour of their community, which explains why companies use them to represent their brands. In fact, according to Influencer Marketing Hub, the value of influencer marketing is expected to reach US$13.8 billion this year.

The engagement relationship between followers and influencers

Influencers tend to present themselves as ordinary people. Publishing daily details about their lives makes them seem authentic and credible to their followers.

When someone follows an influencer, it creates a para-social relationship, which boosts the influencer’s follower engagement and influence. For example, the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that 12 influencers were responsible for spreading 65 per cent of the anti-vaccine content shared on social media between Feb. 1 and March 16, 2021.

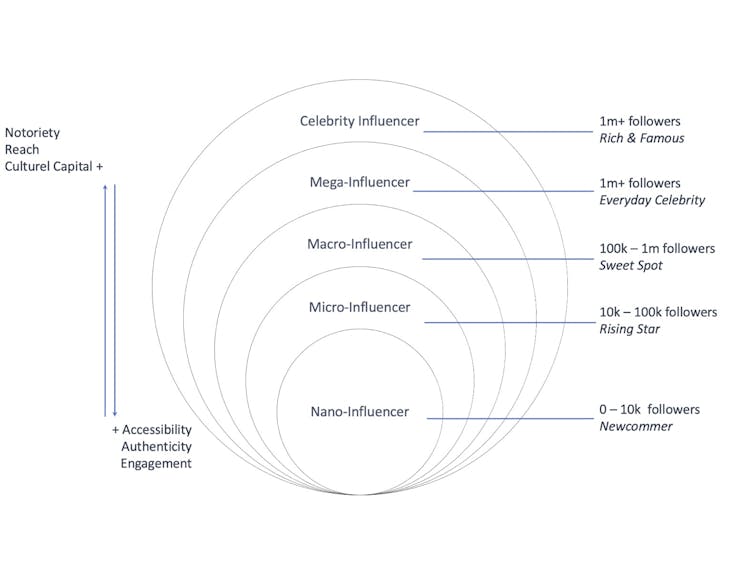

The scientific literature on relationship marketing classifies influencers based on their audience reach and engagement rate. Generally, the fewer followers an influencer has, the more accessible they are and the higher their engagement rate. Followers’ engagement unfolds in three dimensions: cognitive, affective and behavioural.

They can, for example, like or re-share an influencer’s post. However, at its peak, the follower becomes a follower-evangelist — an emerging concept in relationship marketing. This individual believes in an influencer with such fervour that he promotes them to those around him. He becomes an influencer of an influencer by endorsing their gestures, adhering to their ideas and consuming the brands put forward.

Propelled by reality shows

Many influencers obtained their status after joining a reality show, and being bombarded by offers to represent brands.

Some former participants of reality shows such as Love Island and Occupation Double were identified on the Sunwing plane.

These types of shows produce stars based on a notoriety acquired in only a few weeks and not based on any particular talent, except for personality. What comes after a reality show is tempting for many, but not all are ready to become an idol or the target of haters, manage their brand image and those of the brands they represent.

Influencers, but not all on the same plane

Out of 130 passengers, there were possibly 15 influencers on the Sunwing flight.

In this case, the media played up the term “influencer” to promote the story. It’s a shame, because putting all influencers on the same plane ruins the reputation of those who work to share relevant and responsible content.

For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Québec government used a brigade of influencers to educate youth about wearing masks and social distancing. I interviewed some of these influencers as part of one of my studies. They said they felt their role took on meaning by educating their followers for the collective good. By joining their voices to causes, influencers can become ideal standard bearers.

Seizing the opportunity of a marketing coup

The Sunwing saga inspired many to exploit the ridiculousness of the situation. The stand-up comic Arnaud Soly produced an epic live feed on Instagram. Soly plays Devin, one of the influencers on vacation in Tulum, Mexico, who refers to the three V’s of the headline: vodka, Vaseline and vape. Quewbec companies such as Clan Panneton, La Belle et la Boeuf and TAMÉLO also made humorous references to the Sunwing story.

In the meantime, the now-famous organizer of the event, Senior, whose real name is James (Kevin) William Awad, made a live feed to poll his followers about the idea of making a Netflix movie about the saga. The excessive media coverage has raised questions about the source of his wealth and practices .

But the Sunwing case has brought up important social issues. The pandemic and its many restrictions have amplified our need for entertainment, and the party fanned the flames of our own feelings of social deprivation. There’s no doubt the influencers on the Sunwing flight took a risk by posting to their social media feeds, actions that could affect their future careers. Some might also lose lucrative brand contracts.

With the rise of cancel culture in our society, influencers like this become easy to targets for exclusion. However, by giving them too much attention, we also contribute to their excessive media coverage, as well as public exasperation.

Nataly Levesque, Candidate au doctorat en administration des affaires, concentration marketing, spécialisation marque humaine, Université Laval

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.